Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe are in the midst of a moon craze. More and more countries and companies are setting their sights on the lunar surface, competing for resources and space dominance. So are we ready for a new era of lunar exploration?

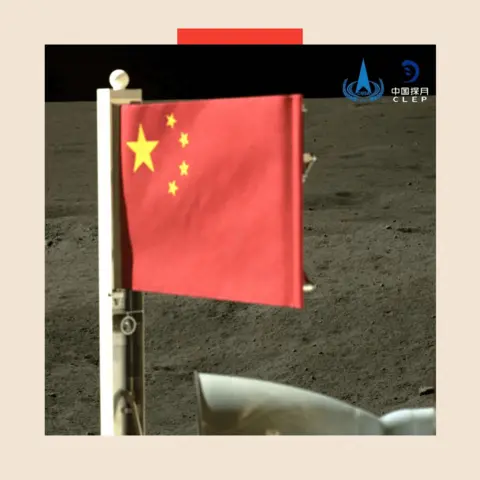

This week, images of the Chinese flag unfurled on the moon were beamed back to Earth. This is the country's fourth lunar landing and the first-ever mission to return samples from the far side of the moon. India and Japan have also launched spacecraft from the lunar surface in the past 12 months. In February this year, US company Intuitive Machines became the first private company to send a lander to the moon, with more companies following suit.

Meanwhile, NASA hopes to return humans to the moon, with its Artemis astronauts aiming to land on the moon in 2026. China says it will put humans on the moon by 2030. The plan is not a short visit but to establish a permanent base.

But in a new era of great power politics, this new space race could cause tensions on Earth to spill over to the lunar surface.

"Our relationship with the moon will soon change fundamentally," warns Justin Holcomb, a geologist at the University of Kansas. He says the pace of space exploration is now "outpacing our laws."

A 1967 United Nations agreement states that no country can own the moon. Instead, the curiously named Outer Space Treaty asserts that it belongs to everyone and that any exploration must be conducted for the benefit of all humanity and for the benefit of all nations.

While it sounds very peaceful and collaborative—and it was—the driving force behind the Outer Space Treaty was not cooperation but Cold War politics.

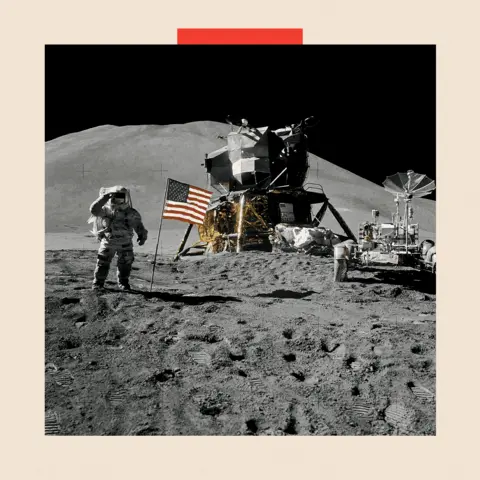

After World War II, as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union increased and there were concerns that space could become a military battlefield, a key part of the treaty was that nuclear weapons should not be launched into space. More than 100 countries signed up to participate.

But this new space age looks different than it did back then.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne big change is that modern lunar missions are not just national projects—companies are competing too.

In January, a U.S. commercial mission called Peregrine announced it would take human ashes, DNA samples and branded sports drinks to the moon. The fuel leak meant it never got there, but it sparked debate about how delivering such an eclectic stockpile would fit in with the treaty's principle that exploration should benefit all humanity.

"We started sending things out there just because we could. There was no rhyme or reason anymore," said Michelle Hanlon, a space lawyer and founder of For All Moonkind, an organization dedicated to To protect the Apollo landing site. "We have the moon within reach, but now we're starting to abuse it," she said.

But Saeed Mostshahr, director of the Institute of Space Policy and Law in London, said that even as private enterprise on the moon continues to increase, nation-states will ultimately remain the key players in all this, and any company will need to obtain authorization to enter space by Developed by the state and restricted by international treaties.

There's still a lot of prestige to be gained by joining the Moonshot elite club. After a successful mission, India and Japan can well claim to be global space players.

A country with a successful space industry can significantly boost its economy through jobs and innovation.

But the race to the moon offers an even bigger prize: its resources.

While the lunar terrain appears to be quite barren, it contains minerals, including rare earths, metals like iron and titanium, as well as helium, which is used in everything from superconductors to medical devices.

Estimates of the value of all these vary widely, ranging from billions to quadrillions. So it's easy to see why some people see the moon as a place to make a lot of money. However, it's also important to note that this will be a very long-term investment, and the technology required to extract and return these lunar resources is still some way off.

In 1979, an international treaty declared that no country or organization could claim the resources there. But it wasn't popular - only 17 countries joined, and that doesn't include anyone like the United States who has been to the moon.

In fact, the United States passed a law in 2015 allowing its citizens and industry to extract, use and sell any space material.

“This caused huge consternation in the international community,” Michelle Hanlon told me. “But slowly, other countries followed suit and enacted similar national laws.” These include Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, Japan and India.

Surprisingly, the most needed resource is water.

"When the first moon rocks were brought back by humans Apollo astronauts After analysis, they were deemed to be completely dry," explained Sarah Russell, professor of planetary science at the Natural History Museum.

"But there was a revolution about 10 years ago when we discovered that their phosphate crystals contained trace amounts of water."

Reuters

ReutersAt the moon's poles, she said, there are even greater reserves of water ice frozen in permanently shadowed craters.

Future tourists could use the water for drinking, it could be used to generate oxygen, and astronauts could even use it to make rocket fuel, breaking it down into hydrogen and oxygen, allowing them to travel from the moon to Mars and beyond.

The United States is currently trying to develop a new set of guiding principles around lunar exploration and development. The so-called Artemis Accords stipulate that the extraction and use of resources on the moon should be done in a manner consistent with the Outer Space Treaty, although it says some new rules may be needed.

To date, more than 40 countries have signed these non-binding agreements, but notably, China is not on the list. Some believe new rules for lunar exploration should not be dictated by a single country.

“This really should be done through the United Nations because it affects all countries,” Saeed Mosteshal told me.

But access to resources can also trigger another conflict.

While there's plenty of space on the moon, areas near ice-filled craters are the moon's prime real estate. So what happens if everyone wants the same location as their future base? Once one country has established a base, what can stop another country from establishing a base too close to them?

“I think there’s an interesting analogy to the Antarctic,” said Jill Stewart, a space policy and law researcher at the London School of Economics. "We may see research bases established on the moon as we do on the continent."

But specific decisions about a new moon base, such as covering a few square kilometers or hundreds of square kilometers, may depend on who gets there first.

"There's definitely a first-mover advantage," Jill Stewart said.

"So if you can get there first and set up camp, then you can figure out the size of the exclusion zone. It doesn't mean you own that land, but you can sit on that space."

For now, the first settlers are likely to be the United States or China, bringing new competition to an already strained relationship. They're likely to set the standards—the rules set by whoever gets there first may end up being the rules that stick in the long term.

If this all sounds a bit temporary, some space experts I spoke to think it's unlikely we'll see another major international space treaty. The considerations for lunar exploration are more likely to be determined through a memorandum of understanding or a new code of conduct.

The stakes are high. The moon is our eternal companion and we watch it shine brightly in the sky and go through different phases of waxing and waning.

But as this new space race begins, we need to start thinking about what kind of place we want it to be, and whether it has the potential to be a place for competition here on Earth.

BBC in-depth report is the new home of websites and apps delivering the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a unique new brand, we'll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and in-depth coverage of the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. We'll also be showcasing thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We start small but think big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.