Getty Images

Getty ImagesElon Musk hopes his new rocket will revolutionize the space industry. The rocket, called Starship, is now the largest and most powerful spacecraft ever built.

It is also designed to be completely and quickly reusable. His private company, SpaceX, is behind the invention, which hopes to develop a spacecraft that operates more like an airplane than a traditional rocket system, capable of landing, refueling and taking off again hours after landing.

What happened with the latest launch?

Starship's fifth test flight on October 13 was its most successful.

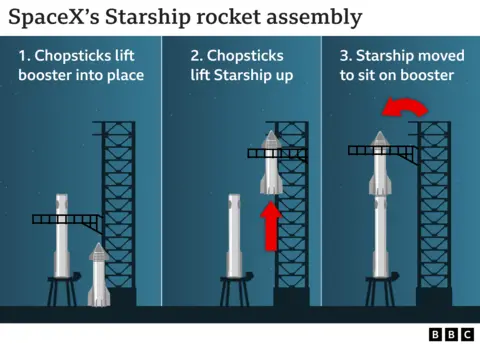

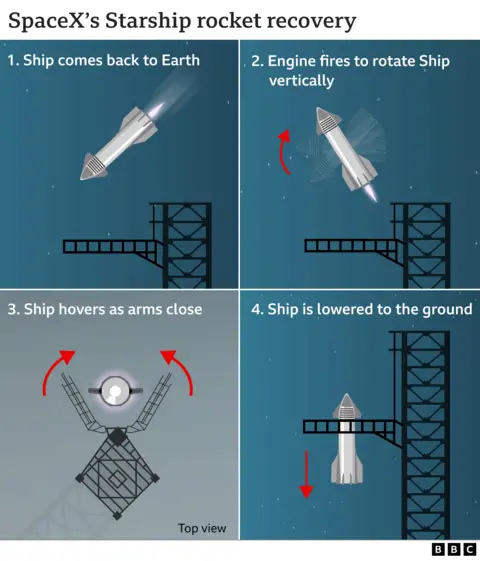

For the first time ever, SpaceX has successfully moved the bottom of the vehicle (the Super Heavy booster) back to the launch pad. Once there, it hovered and was captured in mid-air by a pair of giant robotic arms on the launch tower.

SpaceX wants its spacecraft to be reusable quickly, and the quickest way to do that is to bring the rocket's components back to their starting locations.

SpaceX hopes to eventually grab hold of the spacecraft the same way — the top part of the vehicle.

But that didn't happen on the fifth test flight, which landed in the Indian Ocean exactly as planned.

Will Starship go to Mars?

So far, none of Starship's missions have been crewed, and there are no plans to send people on the next flight.

But Musk and company do have big plans for a rocket system that will one day take humans to Mars.

The journey to Mars is not yet here. But the behemoth rocket already boasts some impressive specs and dwarfs all of its predecessors.

How big and powerful are starships?

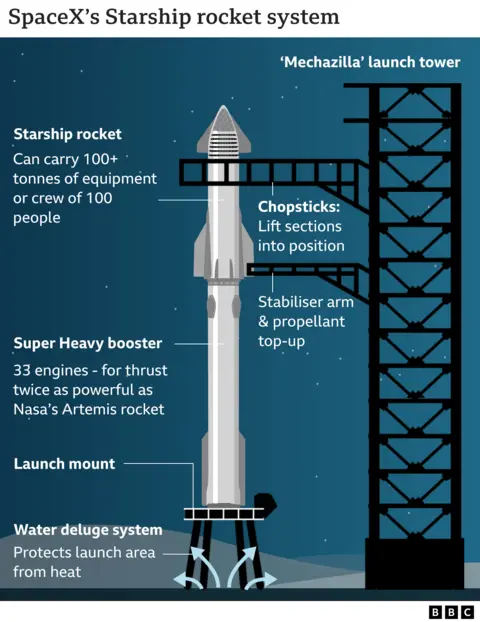

A starship is a two-stage aircraft. The "ship" is the uppermost section, sitting on top of a booster called Super Heavy.

The 33 engines at the bottom of the booster can produce about 74 meganewtons of thrust. To put that into perspective, it has almost 700 times the thrust produced by a regular passenger aircraft, the Airbus A320neo.

If you've flown with Aer Lingus, British Airways or Lufthansa, imagine the thrill of taking off on one of these aircraft. Then multiply by 700.

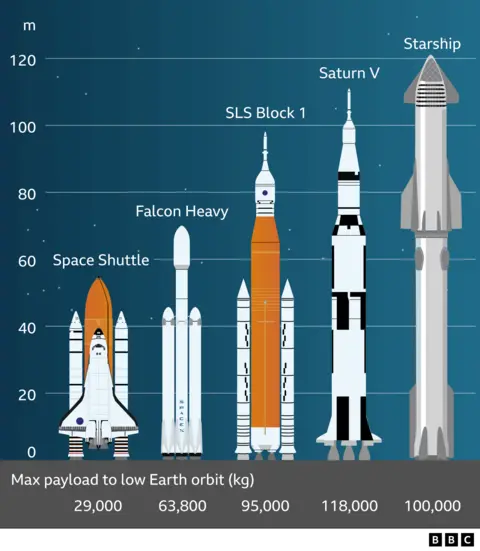

The vehicle has grown by about a meter since its second test flight in June this year, with Starship now having a total length of just over 120m.

This extra height comes from the Super Heavy booster itself being 1m longer.

It is about twice as powerful as the Saturn V rocket that first brought humans to the lunar surface.

SpaceX said the power should be able to transfer payloads weighing at least 150 tons from the launch pad to low Earth orbit.

Both the ship and the Super Heavy booster are fueled by a mixture of icy liquid methane and liquid oxygen fuel called methoxyphosphorus.

What has Starship done so far?

Starship has conducted four test flights so far. On the first flight, the rocket system exploded prematurely before the boosters could separate.

It's worth noting that such issues are part of SpaceX's plan to speed up development by launching systems they know are imperfect and learning from their mistakes.

Real progress was made with each test - first with a smooth separation and ultimately with a successful return, with both spacecraft and booster making controlled descents, circling over the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, respectively, until splashdown.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow do starships land?

space exploration technology corp.

space exploration technology corp.As the booster returned to Earth, anyone watching nearby could predict a thunderous roar as the booster decelerated from supersonic speeds.

Although SpaceX plans to use the launch tower to capture the booster, we will not see a similar return of the top component (the spacecraft) this time. When we do that, it shouldn't look much different than the super heavy descent.

But since there are no launch towers on Mars or the Moon, the spacecraft also needs to be able to land on its legs.

To do this, it maneuvers itself horizontally as it begins its descent, a move Musk calls a "belly flip." This increases the vehicle's drag, slowing it down.

space exploration technology corp.

space exploration technology corp.Once the craft is close enough to the water, it slows down enough to fire its engines in a way that flips the vehicle into a vertical position.

The spacecraft then uses rockets to guide itself safely down, landing on hard pads on its landing legs.

All of this had been accomplished by the spacecraft on previous flights - except for landing on the tarmac. So far it has only made landfall in the sea.

What are the challenges?

One of the purposes of test flights is to highlight problem areas, and the quick turnaround between each test flight means weak links have to be redesigned at lightning speed.

If something goes wrong, the rocket's entire internal structure could melt from the hot gases.

space exploration technology corp.

space exploration technology corp.What else is a starship used for?

Starship will soon have some uses.

So far, Musk has launched his own commercial satellite, known as Starlink, using his own rockets such as the Falcon 9 series.

The lifespan of these satellites is very short, about five years, and the constellation of satellites in orbit needs to be constantly replenished to maintain the same number of satellites in space.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNASA also hopes to use Starship as part of its Artemis program, which aims to establish a long-term human presence on the moon.

NASA

NASAIn the more distant future, Musk hopes Starship will be able to make long-distance trips to Mars and back — about nine months each way.

"If you really wanted to squeeze people in, you could imagine five or six people per cabin. But I think for the most part we would expect to see two to three people per cabin, so nominally There were about 100 people on the flight to Mars," Musk said.

The idea is to put part of the spacecraft into low-Earth orbit and "park" it there. It can then be refueled in orbit via SpaceX's "tanker," essentially another windowless spacecraft, to continue its journey to Mars.

It is also conceivable that starships could be used to launch space telescopes.

The Hubble Telescope is about the size of a bus, and the James Webb Telescope is nearly three times the size of a bus.

To quickly launch thousands of satellites or larger telescopes, you need a large rocket.

Finally, Starship could also carry the weight needed to build a space station and eventually the infrastructure for a human presence on the moon.

How much greenhouse gases does Starship emit?

The kicking power of a rocket is 700 times that of a passenger plane, so it will inevitably have some impact on the environment.

A draft environmental report released by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in July showed that the new license SpaceX is applying for will allow them to launch Starship 25 times per year.

The FAA said this would emit a total of 97,342 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, or 3,894 tons per launch.

By comparison, an average car in the United States emits about 4.6 tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

If we crunch the numbers, that means one Starship launch emits as much greenhouse gas as 846 cars emit in a year.

From a pure numbers perspective, this is pretty insignificant compared to the commercial aviation industry.

But those numbers may start to increase as Musk looks to increase the number of launches to hundreds per year in the future.