Technical Reporter

The Svalbard is above the Arctic Circle, located between the Norwegian continent and the Arctic.

It is frozen, mountainous and far away, and it is home to hundreds of polar bears and several sparse settlements.

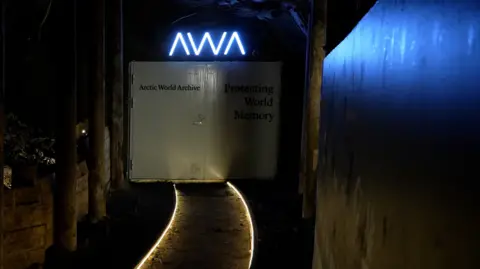

One of them is Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town, outside of the settlement, in a retired coal mine, is the Arctic World Archives (AWA) - the Data Underground Library.

Customers pay to store data on film and keep it in vaults, which can be hundreds of years.

"It's a place that ensures that information can survive where technology is outdated, time and age. It's our mission," founder Rune Bjerkestrand said.

Opening the headway we descended a dark passage and followed the old rail track 300 meters to the hillside until we reached the metal door of the archives.

In the vault, there is a transport container with silver packaging, each collection contains a reel of film and stores data on that film.

"It's a lot of memories, a lot of legacy," Mr. Bjerkestrand said.

“It’s a digital work of art, literature, music, movie, you can name it.”

Since the archives were released eight years ago, institutions, companies and individuals have more than 100 deposits from more than 30 countries.

Among many digital artifacts, there are 3D scanning and models of the Taj Mahal. The Ancient Manuscript Division from the Vatican Library; the satellites observing the Earth from space; and the precious Norwegian painting, The Scream.

AWA is a commercial operation that relies on technology provided by Norwegian data protection company PIQL, and Mr. Bjerkestrand is also responsible.

It was inspired by the global seed insurance company, a seed bank that is only a few hundred meters away, a repository for recycling crops after natural or man-made disasters.

“Today, information and data have a lot of risks,” Mr. Bjerk Stands said. “There are terrorism, war, cyber hackers.”

According to him, Svalbard is the ideal place to host secure data storage facilities.

"It stays away from everything! Stay away from war, crisis, terrorism, disaster. What could be safer!"

Underground it is dark, dry and cold, with temperatures below zero throughout the year; the conditions Mr. Bjerkestrand claims are ideal for keeping the film safe for centuries.

If global warming causes thick Arctic permafrost to melt, the vault is still strong enough to retain its contents.

At the back of the conference hall, another large metal box contains GitHub's code base.

Here, the software developers archive hundreds of reels of open source code that are the basis for computer operating systems, software, websites, and applications.

It also stores programming languages, AI tools, and every active public repository written by 150 million users on its platform.

"For humans, ensuring the future of humanity is very important to our daily lives, and it is very important to our daily lives," Kyle Daigle, chief operating officer of Githhub, told the BBC.

He said his company explores a variety of long-term storage solutions and has challenges. “Some of our existing mechanisms can be stored for a long time, but you need technology to read them.”

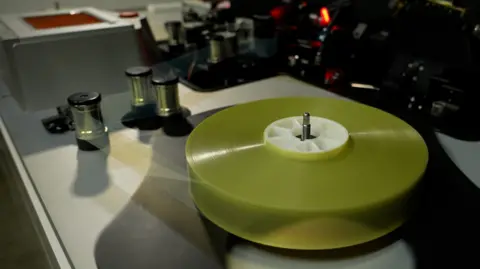

At the PIQL headquarters in southern Norway, data files are encoded into photosensitive films.

"Data is a series of fragments and bytes," explains Alexey Mantsev, a senior product developer.

"We convert the order of bits from customer data into images. Each image (or frame) is about 8 megapixels."

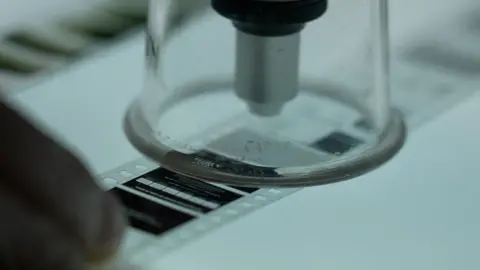

Once these images are exposed and developed, the processed film will appear gray, but watch more closely, it resembles a large number of tiny QR codes.

This information cannot be deleted or changed and it is easy to retrieve Mr. Mantsev.

“We can scan it and decode the data in the same way as the hard drive reads it, but we will read the data from the movie.”

A key question arises from long-term storage methods is whether people will understand what has been preserved and how to restore it, which has been centuries.

This is a situation that PIQL has also considered, so it is also possible to print the guide that can be amplified and optically read in the movie.

More data is used and generated every day than ever, but experts have long warned of the potential “digital dark age” as technological advances have made previous software and hardware obsolete.

This could mean the files and formats we are using now, facing a similar fate to those of the past floppy disks and DVD drives.

Many companies provide long-term data storage.

The most common form is tape cassettes called LTO (linear tape opens), but new innovations are expected to revolutionize the way we keep information.

For example, Microsoft's Project Silica has developed a 2mm thick glass pane and transports a large amount of data into it by a powerful laser.

Meanwhile, a team of scientists at the University of South Hampton created a so-called 5D memory crystal that preserves records of the human genome.

This is also placed in a memorial human repository, another safe that secures historical documents, hidden in Austria's salt mines.

The Arctic World Archives receives three deposits a year, and with the BBC visit, recordings of endangered languages and manuscripts by composer Chopin, are one of the latest reels in the safe.

Photographer Christian Clauwers has been documenting South Pacific islands threatened by sea level rise, and he has added his work.

"I stored the lenses and photography, visual witnesses of the Marshall Islands," he said.

“The highest point of the island is three meters, and they are facing the huge impact of climate change.”

“It’s really humble and surreal,” said Joanne Shortland, archivist at the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust’s Heritage Collection, after storing records, engineer drawings and photos of historic car models.

“I have all these formats that are outdated.

“You need to keep changing the file format and make sure it is accessible for 20 or 30 years. There are a lot of problems in the digital world.”