BBC African Health Correspondent, Lagos

Nafisa Salahu was in danger of becoming another statistic in Nigeria when he was 24 years old, where a woman died every seven minutes on average.

Starting labor during a doctor's strike means that despite being discharged from the hospital, there is no expert help once complications occur.

Her baby's head was stuck and had just been told to stay still during labor, which lasted for three days.

Finally, a caesarean section was recommended and a doctor was found to be ready for it.

Ms. Sarahu told the BBC from the Kano State University (BBC) in the north of the country that he said: “I thank God because I am about to die.

She survived, but her child died.

In eleven years, she returned to the hospital for a few times and adopted a fatalistic attitude. "(Every time) I know I'm between life and death, but I'm no longer afraid," she said.

Ms. Salahu’s experience is not uncommon.

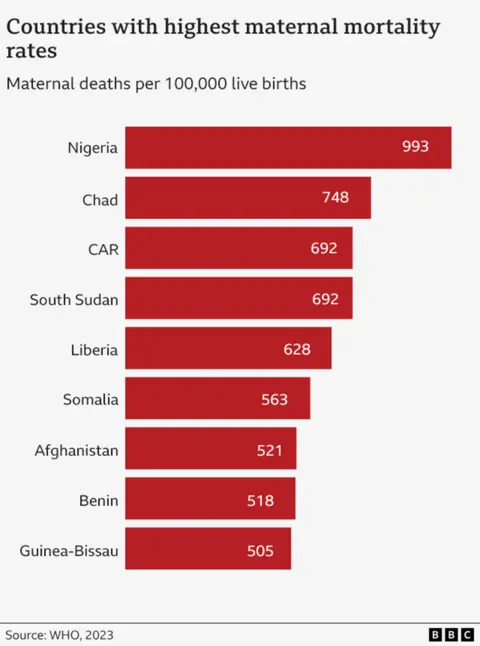

Nigeria is the most dangerous country in the world.

According to the latest UN estimates of the country, the country compiled 2023 figures, with one woman dying in labor or in the next few days.

This makes no country want to lead the top of the league.

In 2023, Nigeria accounts for more than a quarter of all maternal deaths worldwide.

This is a total of 75,000 women die in childbirth in a year, and die every seven minutes.

Warning: This article contains images depicting childbirth

Henry Edeh

Henry EdehWhat many people are frustrated is that many deaths can be prevented - from bleeding after delivery (called postpartum bleeding).

Chinenye Nweze was only 36 years old when he was bleeding at a hospital in the southeastern town of Onitsha five years ago.

"The doctor needs blood," her brother Henry Edee remembers. "They are not enough blood, they are running around. Losing my sister, my friends have no hope for the enemy. The pain is unbearable."

Other common causes of maternal death include labor, high blood pressure and unsafe miscarriage.

According to Martin Dohlsten of the United Nations Children's Organization's UNICEF Nigeria office, Nigeria's "very high" maternal mortality rate is the result of many factors.

He said that these include poor health infrastructure, shortage of medical staff, expensive treatments that many cannot afford, which can lead to some distrustful medical professionals and cultural practices of insecurity.

"No woman should die when she has a child," said Mabel Onwuemena, national coordinator of the Purpose Women's Development Foundation.

She explained that some women, especially in rural areas, think that “going to the hospital is a total waste of time” and then choose “traditional remedies rather than seeking medical help, which may delay life-saving care.”

For some people, it is nearly impossible to get to a hospital or clinic due to the lack of transportation, but Ms Onwuemena believes that even if they manage to do it, their problems will not end.

“Many healthcare facilities lack basic equipment, supply and well-trained personnel, so it’s difficult to provide quality services.”

The federal government of Nigeria is currently spending only 5% of its budget on health, far less than the targets the country promised in the 2001 African Union Treaty.

In 2021, there were 121,000 midwives with a population of 218 million, and less than half of them were supervised by a skilled health worker. It is estimated that the country needs more nurses and midwives to reach the recommended ratio of the World Health Organization.

Severe lack of doctors.

The shortage of staff and facilities has led some to seek professional help.

"I honestly don't trust hospitals very much, I'm negligent, especially in public hospitals," said Jamila Ishaq.

She explained: "For example, when I had my fourth child, there were complications during the delivery process. The local biological waiter suggested we go to the hospital, but when we got there, there was no health care worker who could help me. I had to go home, which is where I ended up giving birth."

The 28-year-old boy from Kano State University is now looking forward to her fifth child.

She added that she would consider going to a private clinic, but the cost is high.

Chinwendu Obiejesi, who is expecting her third child, will be able to pay for private health care at the hospital and "will not consider giving birth anywhere else".

She said maternal deaths are rare now among her friends and family, and she once heard of them frequently.

She lives in a wealthy suburb of Abuja where hospitals are easier to reach, better roads, and emergency services work. More and more women in the city are also educated and know the importance of going to the hospital.

"I always attend prenatal care...it allows me to talk to the doctor regularly, do important tests and scans, and track my health and babies," Ms Obiejesi told the BBC.

"For example, during my second pregnancy, they wished I might be bleeding a lot, so they prepared extra blood just in case they needed a blood transfusion. Fortunately, I didn't need it and it went well."

However, her family was not lucky.

During her second labor, "the biological waiter was unable to give birth to the baby and tried to force it. The baby died. By the time she was taken to the hospital, it was too late. She still had to undergo surgery to give birth to the baby's body. It was heartbreaking."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr. Nana Sandah-Abubakar, director of community health services at the country's National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), acknowledged that the situation was horrible, but said new plans were being developed to address some issues.

In November last year, the Nigerian government launched a pilot phase of the Maternal Mortality Innovation Program (MAMII). Ultimately, this will target 172 local government areas in 33 states, accounting for more than half of all birth-related deaths in the country.

"We identify every pregnant woman, knowing where she lives and supporting her through pregnancy, childbirth and beyond," said Dr. Sandah-Abubakar.

So far, 400,000 pregnant women in six states have been found in a House survey, “detailed description of whether they have participated in static (class) (class).

“The plan is to start linking them to services to ensure they are cared for (needed) and delivered safely.”

MAMII will aim to work with local transportation networks to try to get more women to clinics and encourage people to sign up for low-cost public health insurance.

It is too early to say whether this has any impact, but authorities hope that the country can eventually follow trends in the rest of the world.

Since 2000, maternal deaths have dropped by 40% as access to health care expands. During the same period, Nigeria's figures also improved - but only increased by 13%.

While Mamii and other programs are welcome, some experts believe that more things must be done – including more investment.

"Their success depends on ongoing funding, effective implementation and ongoing monitoring to ensure the achievement of the expected results," said UNICEF's Dohlsten.

Meanwhile, the loss of every mother in Nigeria every day - 200 people per day - will continue to be a tragedy for the families involved.

For Mr. Ed, the grief over the loss of his sister remains primitive.

“She stepped up to be our anchor and backbone because we lost our parents when we grew up,” he said.

"In my lonely time, when she crossed my mind. I cried in pain."

More BBC stories from Nigeria:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC