Given their abundance in U.S. backyards, gardens and highway corridors these days, it might be surprising to find whitetail deer nearly extinct a century ago. Although their current number is 30 million to 35 million, in the early 20th century, the white tail of the entire continent had only 300,000 white tails: 1% of the current population.

At that time, this near-divergence of deer was discussed. In 1854, Henry David Thoreau wrote that there was no hunted generation near Concord, Massachusetts. In his famous "Walden", he reports:

"One man still retained the horns of the last deer killed in this neighborhood, and another told me the details of his uncle's engagement. The hunter used to be a multitude and happy crew here."

But what happened to the white-tailed deer? What drove them almost extinct and then what made them retreat from the edge?

As a historical ecologist and environmental archaeologist, I did my work to answer these questions. Over the past decade, I have studied white-tailed deer bones from archaeological sites in the eastern United States, as well as historical records and ecological data to help piece together the story of this species.

The rise of colonization of deer populations

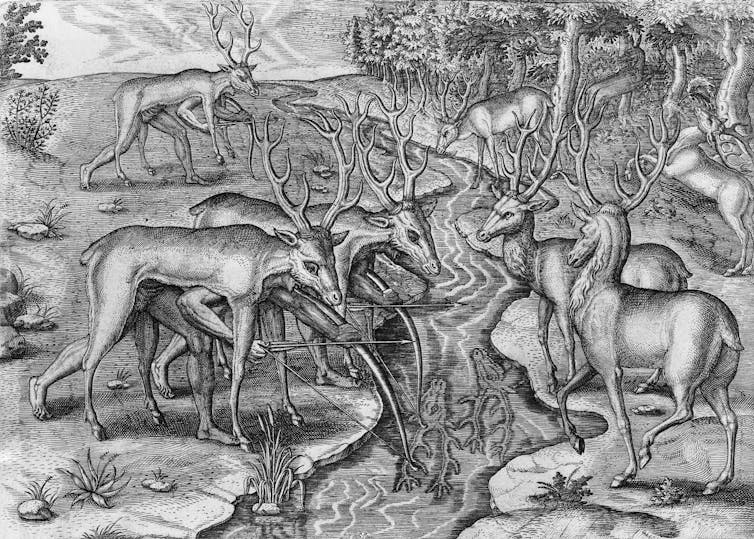

Whitetail deer has been hunted from the earliest migrations of people from 15,000 years ago to North America. However, this species was far from the most important food resource at the time.

Archaeological evidence shows that the abundance of white-tailed deer only begins to increase after giant species like mammoths and masts have become extinct, opening up the ecological walls for deer. Deer bones became very common in archaeological sites about 6,000 years ago, reflecting the economic and cultural importance of the species to indigenous peoples.

Despite being often hunted, deer populations did not appear to have significantly decreased due to indigenous hunting before 1600 AD. Unlike elk or stfish, the number of elk or stfish is reduced by indigenous hunters and fishermen, white-tailed deer appears to be resilient to human prey. Although archaeologists have found some evidence of an artificial decline in some parts of North America, other cases are more ambiguous, and deer must have remained abundant over the past few thousand years.

Human use of fire can partially explain why white-tailed deer may be resilient to hunting. Indigenous peoples across North America have long used controlled burns to promote ecosystem health, disrupting old vegetation to promote new growth. Deer likes this successor vegetation that inherits food and mulch and thus thrives in previously burning habitats. Therefore, indigenous people may have contributed to the population growth of deer, offsetting any harmful hunting pressure.

More research is needed, but even if the obvious hunting pressure is obvious, the general situation in the colonial era is that deer seems to have been in good condition for thousands of years. Ecologists estimate that on the eve of European colonization, there were about 30 million white-tailed deer in North America - about the same number as today.

Deer population declined during the colonial era

To better understand how the deer changes during the colonial era, I recently analyzed deer bones from two archaeological sites in Connecticut now. My analysis shows that the hunting pressure on white-tailed deer almost increased after the arrival of European colonists.

In a location from the 11th to the 14th century (before European colonization), I found that only about 7 to 10% of deer were juveniles.

If hunters often encounter adults, hunters usually don't take deer, as adult deer tends to be larger and can provide more meat and a larger fertility. Furthermore, hunting increases the mortality rate of deer herds but does not directly affect fertility, so deer populations experiencing hunting stress will eventually be at a juvenile-related age structure. For these reasons, the proportion of juvenile deer before European colonization was low, indicating that there was little pressure on local cattle hunting.

However, in the nearby sites occupied in the 17th century (after European settlement), 22 to 31% of deer hunting were juveniles, indicating a significant increase in hunting pressure.

This increased hunting pressure may be due to the conversion of deer into commodities. Venison, antlers and Diskins may have been exchanged in the Indigenous trade network for a long time, but in the 17th century, things changed drastically. European colonists integrated North America into a transatlantic capitalist economic system with no precedent in indigenous societies. This has brought new pressure on the mainland's natural resources.

Deer, especially their skins - were initially commercialized and sold in colonial markets, and by the 18th century, it was also in Europe. Deer are now exploited by traders, merchants and manufacturers, not just hunters who want meat or leather. It is the resulting hunting pressure that drives the species to its extinction.

The 20th century white-tailed deer rebound

Thanks to the rise of conservation movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white-tailed deer survived the extinction brush.

Citizens and outdoor workers concerned about the fate of deer and other wildlife and have pushed for new legislation to protect.

For example, the Lacey Act, which prohibits interstate transport of poaching games and combines state-level protection, ends commercial deer hunting by effectively reducing the species effectively. In areas where conservation-oriented hunting habits and reintroduced deer from surviving populations to extinct, white-tailed deer rebounds.

The story of the white-tailed deer emphasizes an important fact: humans do not inherently harm the environment. Hunting from the 17th to 19th centuries threatened the existence of white-tailed deer, but indigenous hunting and environmental management in the former colonies seemed relatively sustainable, and in the 20th century modern regulatory governance was suppressed and reversed the imminent extinction.