Terrorist attacks are more common during security and economic crises, but terrorist attacks have been reduced during humanitarian disasters.

This is our main finding of our in-depth analysis of global data from 1980 to 2014. During that time of 169 countries, the incidents of terrorist attacks, we found that the perpetrators focused on what we call “maturity moments” – a unique opportunity to attack terrorist organizations when states are distracted or weakened.

But our research shows why states may be vulnerable to terrorists – the chances of greater "reputation risks" are lower, our research shows.

We divide the moment of maturity into three crisis categories: security, economics, and humanitarianism.

Security crises, such as war or threats from competitor countries, absorb the attention and military resources of the state. This creates internal vulnerability and terrorist attacks become more likely.

Similarly, the economic crisis shifted government resources to financial recovery, eroding bureaucracy and military effectiveness. This also reduces the state's ability to monitor and counter terrorist threats. Similarly, we found a clear improvement in terrorist attacks.

Instead, humanitarian crises – especially natural disasters – have triggered different reactions. Although the country is in a weak position, terrorist activities tend to be greatly reduced.

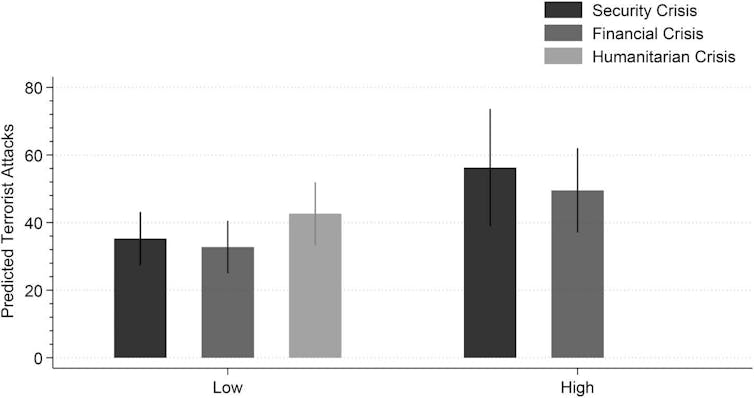

Our findings show that as the security crisis escalates from low hostilities to interstate wars, the chances of terrorist attacks have increased significantly - from 35 to 57 per year, up 1.5 times during the financial crisis. In contrast, the humanitarian crisis corresponds to a sharp drop in predicted attacks, from 43 to less than 1.

The main differences between the three crises - security, economic and humanitarian - are not the fragility of the state, but the reputational risks involved in exploiting such weakness.

This supports our entry into the core theory of research: terrorist organizations take strategic actions to balance the benefits of exploiting crises with potential reputational consequences.

Indeed, armed groups did not use humanitarian disasters to attack and attack, but used them to win the local population. For example, during the 1999 earthquake in Türkiye, the PKK (a group designated by Türkiye and the United States as “terrorists”) not only avoided attacks, but also provided support and donated blood. Similarly, Indonesia's Free ACEH campaign announced a ceasefire and provided assistance during the 2004 tsunami.

In these cases, the reputational cost of attack in disaster outweighs any perceived welfare. Groups are concerned about alienating their domestic supporters, damaging future recruitment or endangering negotiations with the state.

Why it matters

These findings challenge the simple narrative of armed groups attacking when states are vulnerable.

Instead, armed groups demonstrate their limitations based on how the population will perceive their behavior.

We believe this has a profound impact on how the government responds to terrorism. Understanding the trade-offs of reputation can help governments refine their crisis management and counter-terrorism strategies.

For example, policy makers should not automatically assume that terrorism risks are higher in every crisis. Recognizing this nuance may lead to better allocation of security resources and more effective diplomatic responses.

Our research also highlights the importance of media and public perception. During the humanitarian crisis, public empathy and solidarity make violence particularly annoying.

This sentiment crosses racial, political and ethnic boundaries. Armed groups are keenly aware of this and often take corresponding actions. Therefore, active public diplomacy and transparent crisis management can become deterrents of terrorism.

What do we plan to do next

Although our findings are powerful and can clearly define conclusions, there are still some issues to be explored. A major area of future research is the internal decision-making process of terrorist organizations: how do leaders of these groups assess reputational risks? What role do ranking members play in attack decision-making, especially during crisis?

We also want to explore how third-party sponsors (for example, Iran’s Axis of Resistance) affect terrorist acts during the crisis. External actors may put pressure on the group to show restraint, or vice versa to escalate violence.

The extent to which these sponsors value the reputation of the agent may shape group action in unpredictable ways.

In addition to disasters, the decisions of terrorist organizations have been affected by reputation issues, we also hope to follow up on our research by looking at other moments.

Ultimately, we hope our research will open the door to a more complex understanding of terror behavior.

A brief introduction to the research is a brief view of interesting academic work.