Lucy said she had been worried, but two years ago, she began to feel anxious and started having a panic attack.

"I don't know what happened, nor did my parents," the 15-year-old said. "It's horrible. The attacks will happen without warning. It gets worse and I start putting them in public."

Lucy started missing a lot of schools and stopped socializing. She said it was difficult for parents to see her struggle. “We don’t know what to do or where to go.”

For six months, she tried to control her anxiety herself, but eventually the family decided to pay for a conversation therapy called cognitive behavioral therapy.

Lucy said that there was a big change. Although she still had panic attacks, they were much less frequent and she was returning to school and doing what she loved.

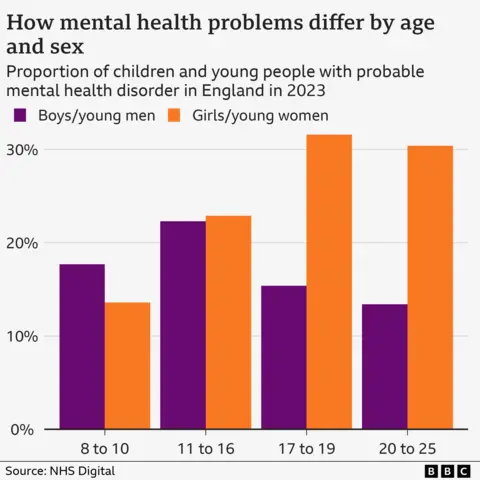

Lucy's story is far from unique. NHS data suggest that one in five children and young people aged eight to 25 have possible mental health disorders.

Why are the problems so common

As teenagers are dealing with growth, test stress, and challenges of friendship and relationships, problems become increasingly common.

Professor Andrea Danese, a child and adolescent psychiatry expert at King's College London, said there are also biological reasons that make emotional health problems more likely.

"The brain of adolescents does not develop at once. The part that processes emotions matures earlier than the part that is responsible for self-control and good judgment. This means that young people can feel things very strongly before fully developing the ability to manage these feelings, which helps explain certain emotions that are rising, which parents often see."

He said that when hormones further enhance emotional responses and change the body’s clock, affecting sleep patterns, the zenith is adolescence.

When and how to help

So, what constitutes a normal emotional challenge – when should teenagers and their parents worry and consider seeking professional help?

Professor Dennis said he understands why many people think it is difficult to judge. He believes that the following are normal teenage emotional characteristics:

- Periodic irritability and moodiness

- Occasional social withdrawal or desire for privacy

- Anxiety about social acceptance or academic performance

- Experimental identity and independence

- Emotional responses seem to be disproportionate

He believes that if these activities don’t interfere with daily activities too much, parents should be able to raise their children.

The most common problems experienced by adolescents are moodiness and anxiety. Professor Dennis said it is important to keep a low mood and maintain healthy habits surrounding eating, sleeping, being active and staying in touch with friends and family, as activities your child enjoys, such as traveling or engaging in exercise.

He added: “And help them identify, break down and try solutions to problems that may arise.”

He said that for anxiety, calming techniques are very helpful. These can include breathing exercises, grounding, you will focus on your surroundings and what you can see, touch and smell, and mindful activities.

"It is important to avoid the pitfalls of providing unnecessary reassurance," Professor Dennis said. Instead, parents should discuss and test the situation of fear under the skills of teaching calm. “To reduce worry, it can help them write down or talk about them once a day of special 'worry time'.”

Building elasticity

Stevie Goulding, who runs a parental helpline for young people, said anxiety is the one they receive the most.

“Many children have anxiety and even panic attacks. This is difficult for parents. It is easy for them to find themselves lacking confidence and judgment.

"The main advice we give to parents is to communicate with children. Allow them to talk about what is bothering them - if they don't want to talk to them, ask if there is anyone else who wants to talk to them."

Ms. Goulding also advises talking to the child’s school, as they may have noticed things as well.

But she added: "There is a need to be given space - avoiding temptations to rush to solve problems. Just reflect what they are saying and listening."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChild psychologist Sandi Mann agrees that parents have an understandable temptation to solve any problems their children face, and that is not necessarily the best solution.

Instead, parents should help their children teach and build resilience, she said, and wrote it for the BBC.

She recommends parents:

- Explain that everyone will have setbacks and give examples of problems in their life

- Embrace error

- Enable them to make their own decisions, stressing that they are largely responsible for their own happiness

- Challenge their beliefs, especially black and white thinking and catastrophic

“I think sometimes we have the impression that children and young people can’t solve their problems when we are anxious to seek help or turn to medication.”

Signs that require professional help

But both Dr. Mann and Professor Dany stress that parents should not shy away from seeking professional support when needed.

“There’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Dr. Mann said. “We just need to know when to try to solve the problem and when to get help.”

Both of them emphasize similar behaviors that should trigger parents to get help. These include:

- Self-harm and suicide thoughts

- Extreme changes in diet or sleep

- Dramatic personality changes and despair expressions

- Major disruptions to daily operations, such as going to school or socializing

- Exiting the activities you once enjoyed for a long time

Dr. Elaine Lockhart, a child and teen teacher at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said parents should be satisfied with raising their mental health with their children and seeking help.

"We know a lot of kids are struggling. It's a fallacy to be the best year of your life."

But with the long waiting time for NHS children’s mental health services, it’s not easy to know where to seek help, especially if you can’t afford private therapy.

The first point of a call is usually your GP or mental health support team that is associated with schools in certain areas. In addition to recommending NHS mental health services, they can also keep you in touch with local organizations and charities that can provide support.

"The school itself can help, too - some people provide counseling and support services," Dr. Lockhart said.

"But I think parents can underestimate the role they can play even if their kids are waiting for support or actually receiving treatment or treatment. Home is where they spend most of their time here - so parents are an important part of the solution."

If you need mental health support, please provide information on how to get help: