Colorado has thick air in June and summer heat. Mosquitoes rise in the clouds around us, testing our determination as we collect cameras and sensors. We walked into the wetland and walked along the unmarked path until the tail foot was raised. The sound of frogs and cricket fills the air as we set the camera and wait. Then we found them: tiny lights raised from the grass, flashing slowly.

Bioluminescent Lampyrid beetles (commonly known as fireflies or lightning bugs) are extensive in the eastern U.S. but are even rarer west of Kansas.

Even though many are stargazers and hikers, most Colorado residents don’t know that fireflies share their state.

We are associate professors and doctoral degrees in computer science. A candidate for the hidden fireflies in Colorado is working to shed light on.

Over the past few years, we have observed and photographed elusive bioluminescent fireflies across Colorado, competing for a short and unpredictable season of flash every summer.

We think it was too early for Colorado fireflies in early June last year. For weeks we have been checking weather forecasts, comparing them to previous years, waiting for warm nights and rising temperatures - which can tell us that this is a sign of firefly time.

Then we got a tip. A friend mentioned seeing a flash or two near their property. The next morning we packed up our gear, rescheduled our schedule, and contacted our network of volunteers. The live season begins literally.

As an adult, fireflies only have about two weeks of life and glitter each year - even then, only a few hours a night. It's easy to wink and miss the whole season. The next generation of underground crosses the larvae and appears in adulthood the next year, although development may require up to two years of drought climate. Making the most of the narrow window is one of many reasons why we rely on volunteers who helped us spot the first flashes and document observations throughout Colorado.

Western fireflies face unique environmental challenges

Our work joins an increasing number of scientific observation choirs focused on Western fireflies that pop up in arid landscapes near temporary wetlands, swamps, drainage, desert rivers and other water sources. Due to the dry landscape, these crowds tend to be dispersed, isolated to the location where the water is, somewhere in between.

This close connection to small, unstable habitat makes fireflies vulnerable. If the water is run out, or its habitat is damaged by water or light pollution, the flickering population may disappear. Pesticides in the water are poisonous to firefly larvae and their prey, and artificial light inhibits flash courtship between males and females, thus preventing successful reproduction. Due to these factors, many populations and species of fireflies are threatened by extinction.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=czt_io0h-ca[/embed]

Our laboratories at the University of Colorado and organizations such as the XERCES Invertebrate Conservation Society are studying the distribution and direct threats of Western firefly populations. Many species are either endangered or not described.

firefly photuris For example, genera along the front range still has no species name and seems to be genetically different from others photuris All over the country. Preliminary genetic results show that at least one new species can be found here. Genetic data also suggest that at least five different bioluminescent species exist in Colorado.

How the flash pattern helps fireflies separate species

During the short mating season, fireflies use their flash patterns as mating phone calls.

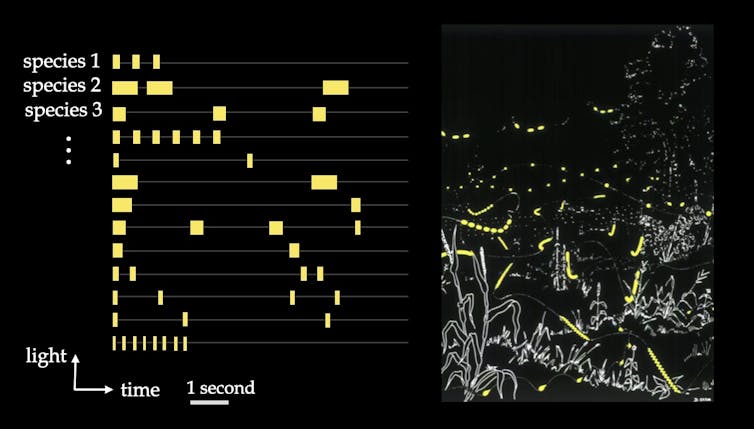

Men produce a series of flashing flicker events, each with a specific duration and pause. These Morse-like code-style signals convey the type and fit of the fireflies’ potential companion in the dark.

When women find the right male, they respond with their own unique glitter pattern.

Our work on this evolutionary adaptation. We first recorded populations from all over the United States using two cameras, which allowed us to accurately track individual fireflies in three dimensions and separate their flash patterns.

We used data from flash behaviors from different species to train a neural network that can classify fireflies with high accuracy. Our algorithm learns unique flash patterns from our data and can identify firefly species present in the video.

This is a powerful tool for firefly protection. Camera lenses can cover more time and ground than live surveys conducted by humans, and our algorithms can identify potentially threatened species faster.

Promote community and citizen science participation

Based on our success in community science data collection in other states including Tennessee, South Carolina, and Massachusetts, we hope to apply the same principles to the Firefly population in Colorado. It's a tough task: There are dozens of debris locations in Colorado, fireflies are active in Colorado, and volunteers report more fireflies every season. During the short firefly season, the team of two of us was unable to access and investigate each site.

In 2023, we announced our first call for volunteers in Colorado. Since then, Fort Collins has joined the shooting for 18 community members in Boulder. We provide cameras for volunteers who take them to nearby wetlands and set them in faded light.

Last summer, we worked with local land management agencies in Fort Collins and Loveland to host informative community events where we talked about firefly biology and conserving audiences of all ages. On many nights, as the flash begins, we hear excitement making: quiet gasps, enthusiastic enthusiasm and whispers, such as: “Look at those beautiful lights!”

Fireflies have an important story to tell, and in Colorado, the story has just begun. Each summer, their brief glitter can help us understand communication, ecology and how these delicate insects cope with the ever-changing world.

If you want to help us find and study fireflies in Colorado, you can sign up to join our community science program.