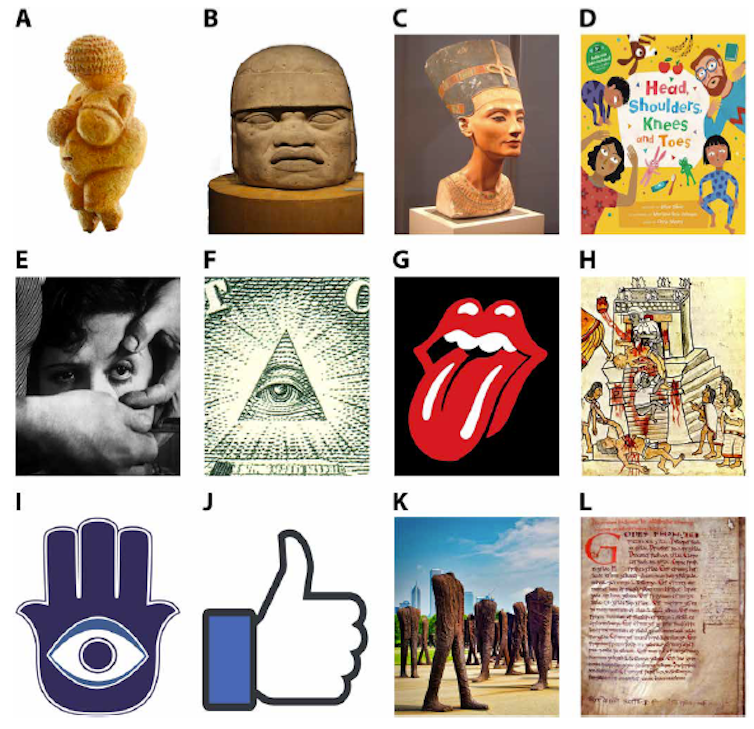

The biblical law of retaliation—“an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot” (Exodus 21:24-27)—has captured the human imagination for thousands of years. This idea of fairness has become a model for ensuring justice when a person is harmed.

Thanks to the work of linguists, historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists, researchers know a lot about how societies large and small, from ancient times to today, value different body parts.

But where did these laws originate?

One school of thought holds that laws are cultural constructs - meaning that they vary from culture to culture and historical period, adapting to local customs and social practices. By this logic, laws regarding physical injury can vary significantly between cultures.

Our new research explores a different possibility—that laws regarding bodily harm are rooted in a universal element of human nature: shared intuitions about the value of body parts.

Do people across cultures and histories agree on which parts of the body are more or less valuable? Until now, no one has systematically tested whether body parts have similar values across space, time, and levels of legal expertise (i.e., between laypersons and legislators).

We are psychologists who study evaluation processes and social interactions. In previous research, we have identified patterns in how people evaluate different wrongdoings, personal characteristics, friends, and foods. The body may be a person's most valuable asset, and in this study we analyzed how people value different parts of the body. We investigate the connection between intuitions about the value of body parts and laws about bodily harm.

How important is the body part or its function?

We start with a simple observation: different body parts and functions have different effects on a person's chances of survival and development. Life without toes is an annoyance. But life without a head is impossible. Can people intuitively understand that different parts of the body have different values?

Knowing the value of your body parts will give you an advantage. For example, if you or a loved one has suffered multiple injuries, you can treat the most valuable body parts first or devote more of your limited resources to treatment.

This knowledge can also come into play in negotiations when one person is hurting another. When person A harms person B, person B or his family may demand compensation from person A or his family. This practice occurs all over the world: among the Mesopotamians, the Tang Chinese, the Enga of Papua New Guinea, the Nuer of Sudan, the Montenegrins, and many more. The Anglo-Saxon word "wergild," meaning "human price," now generally refers to the practice of paying for body parts.

But how much compensation is fair? Asking for too little can result in losses, while asking for too much can result in retaliation. To find a balance between the two, victims seek compensation in a Goldilocks fashion: just right, based on the agreed value placed on the body part in question by the victim, the offender, and third parties in the community.

This Goldilocks principle is evident in the precise proportions of the law of retaliation - "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth." Other laws and regulations specify the precise value of different body parts, but in terms of money or other goods. For example, the Code of Ur-Nammu written in Gunipur (today's Iraq) 4,100 years ago stipulates that if a person cuts off another person's nose, he must pay 40 shekels of silver, but if he knocks the other person unconscious, he must pay 40 shekels of silver. One person only needs to pay 2 shekels of silver. Men's teeth.

Testing the idea across cultures and time

If people have an intuitive understanding of the value of different body parts, could this knowledge form the basis for laws regarding physical harm across cultures and historical eras?

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a study among 614 people from the United States and India. Participants read descriptions of various body parts, such as "an arm," "a foot," "nose," "an eye," and "a molar." We chose these body parts because they feature in the laws and regulations of five different cultures and historical periods we studied: the Laws of Ethelbert in Kent, England, 600 AD, the Laws of Gotland, Sweden, 1220 AD Ancient Tathagata as well as modern legal codes. Workers’ Compensation Laws in the United States, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates.

Participants answered a question about each body part they saw. We asked some people how difficult their daily lives would be if they lost parts of their body in an accident. We ask others to imagine themselves as legislators and determine how much compensation an employee should receive if the employee lost various body parts in a workplace accident. In others we asked participants to estimate how angry the other person would be if the participant damaged various parts of the other person's body. Although these questions are different, they all rely on assessing the value of different body parts.

To determine whether untrained intuition underlies the law, we did not include people with university training in medicine or law.

We then analyzed whether participants' intuitions were consistent with legal provisions for compensation.

What we found was surprising. Laypeople and legislators generally agree on the importance attached to body parts. The more importance a particular body part attaches to an American layman, the more that body part will appear to an Indian layman, to legislators in the United States, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates, to King Ethelbert, and to the author of Qutaraq valuable. For example, laypeople and legislators across cultures and centuries generally believe that the index finger is more valuable than the ring finger, and that an eye is more valuable than an ear.

But do people accurately value body parts in a way that corresponds to their actual functions? There are some signs that, yes, it is. For example, laypeople and legislators view the loss of a single part as less serious than the loss of multiple parts of that part. Furthermore, laypeople and legislators view partial losses as less serious than overall losses; losing a thumb is not as serious as losing a hand, and losing a hand is not as serious as losing an arm.

Further evidence of accuracy can be gleaned from ancient laws. For example, linguist Lisi Oliver points out that in barbaric Europe, "wounds that might result in permanent incapacitation or disability were more penalized than wounds that might ultimately heal."

Although it is generally accepted that some parts of the body are valued more than others, there may be some significant differences. For example, vision is more important to a hunter than a shaman. Local environment and culture may also play a role. For example, upper body strength is especially important in violent areas, where people need to protect themselves from attacks. These differences remain to be studied.

Morality and law, across time and space

Many behaviors that are ethical or unethical, legal or illegal vary from place to place. For example, drinking, eating meat, and cousin marriage were condemned or supported to varying degrees in different times and places.

But recent research also shows that in some areas, across cultures and even over millennia, there is more moral and legal consensus about what is wrong. Wrongful conduct—arson, theft, fraud, trespassing, and disorderly conduct—seems to produce a moral and associated law that is similar across time and place. Laws regarding personal injury also seem to fall under the category of moral or legal universals.