sound pressure level

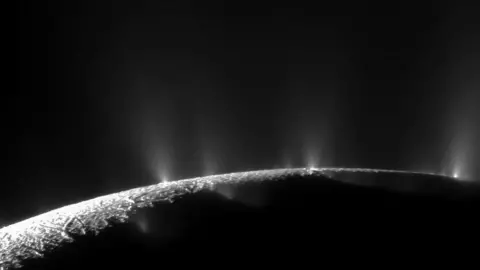

sound pressure levelUranus and its five largest moons may not be the dead, barren worlds scientists have long thought they were.

Instead, they may have oceans and satellites that may even be able to support life, scientists say.

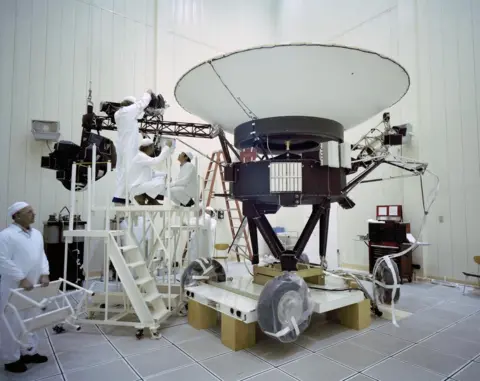

Most of what we know about them comes from NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft, which visited nearly 40 years ago.

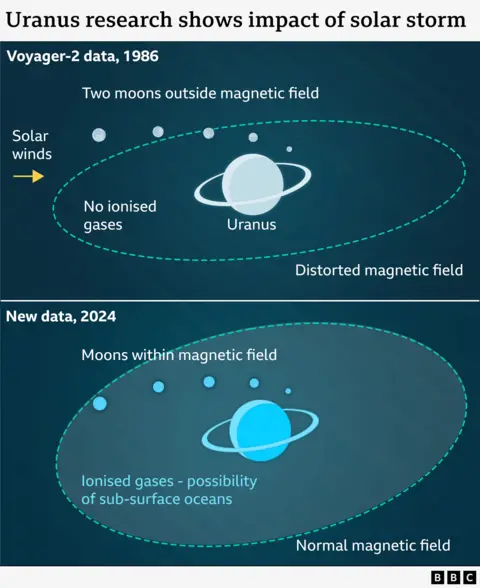

But a new analysis suggests that Voyager's visit coincided with a powerful solar storm, leading to a misleading picture of what the Uranus system really looks like.

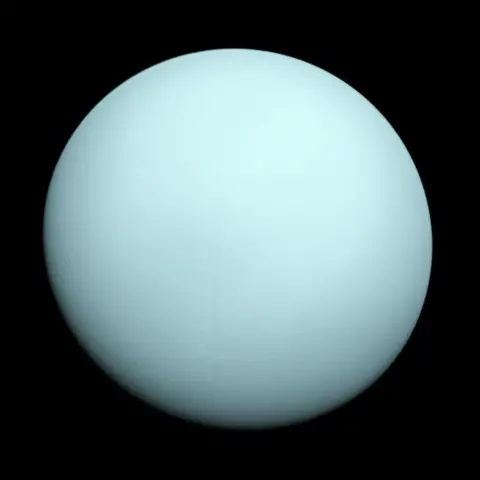

Uranus is a beautiful icy ring world in the outer reaches of the solar system. It is one of the coldest of all planets. Compared to all the other worlds, it's also tilted to one side - as if it's been knocked over - making it arguably the strangest.

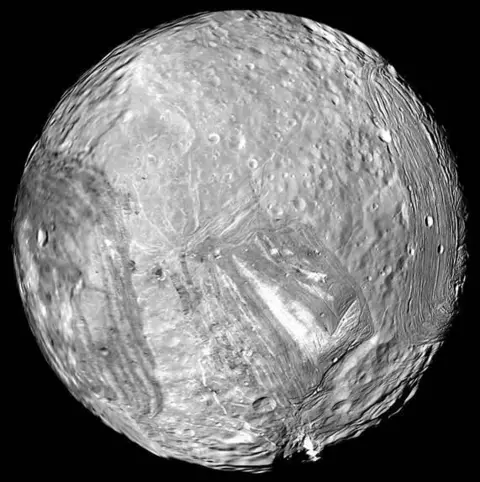

We got our first close look at it in 1986, when Voyager 2 flew by and sent back stunning photos of the planet and its five major moons.

But what surprised scientists even more was the data returned by Voyager 2 that showed the Uranus system was even stranger than they thought.

Measurements from the spacecraft's instruments indicate that, unlike other moons in the outer solar system, the planet and moon are not active. They also showed that Uranus' protective magnetic field is strangely distorted. It was crushed and pushed away from the sun.

A planet's magnetic field traps any gases and other materials from the planet and its moons. These may come from marine or geological activity. Voyager 2 found nothing, suggesting that Uranus and its five largest moons are barren and inactive.

This was a huge surprise because it is unlike the other planets and their moons in the solar system.

NASA

NASA NASA

NASABut new analysis solves a decades-long mystery. It shows that Voyager 2 flew by on a bad day.

New research shows that just as Voyager 2 flew past Uranus, the sun was raging, producing a powerful solar wind that could blow away material and temporarily distort the magnetic field.

So for four decades, we've had a wrong idea of what Uranus and its five largest moons usually look like, says Dr. William Dunn of University College London.

"These results indicate that the Uranus system may be more exciting than previously thought. There may be moons there, there may be conditions necessary for life, and they may have oceans below their surface, full of fish!".

NASA

NASALinda Spilker was a young scientist working on the Voyager program when the Uranus data arrived. She still serves as project scientist for the Voyager mission. She said she was delighted to hear the new results Published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"The results are fascinating and I'm excited to see the potential for life in the Uranus system," she told BBC News.

"I'm also pleased to see so much use of the Voyager data. It's amazing that scientists look back at the data we collected in 1986 and discover new results and discoveries."

Dr Affelia Wibisono of the Institute for Advanced Study in Dublin, who was independent of the research team, described the results as "very exciting".

"This shows how important it is to look back at old data, because sometimes, hidden behind them is something new to be discovered, which can help us design the next generation of space exploration missions."

That's exactly what NASA is doing, in part as a result of this new study.

It's been nearly 40 years since Voyager 2 last flew by this icy world and its moons. NASA plans to launch a new mission, the Uranus Orbiter and Probe, to return in 10 years for a closer look.

NASA

NASAIt was the idea of NASA's Dr. Jamie Jasinski to re-examine the Voyager 2 data, and the mission needed to take his results into account when designing instruments and planning scientific investigations.

"The design of some of the instruments on future spacecraft will be largely based on what we learned when Voyager 2 flew through the system when it experienced an unusual event. So we need to rethink how to accurately design new instruments on the mission so that we can best capture the science needed to make the discovery."

When NASA's Uranus probe is expected to arrive in 2045, scientists hope to find out whether these distant, icy moons, once thought to be dead worlds, could potentially be home to life.