Music correspondent

35 seconds. That's where you've been changing scenes on the European TV network.

Thirty-five seconds to get a group of performers off the stage and then put the next performer in the right position.

Thirty-five seconds to make sure everyone has the right microphone and earpiece.

35 seconds to ensure the props are in place and secure.

When you watch an introductory video called a postcard at home, dozens of people flock to set up the scene for whatever comes next.

“We call it the Formula One tire change,” said Richard Van Rouwendaal, Dutch stage manager who made it all work.

"Everyone in the crew can only do one thing. You run on the stage with a light bulb or a prop. You always walk on the same line. If you leave the route, you hit someone.

“A little like skating.”

Stage staff began rehearsing their "F1 tire changes" just weeks before the contestants arrived.

Each country sends detailed plans, as well as Eurovision hires a substitute action (in Liverpool 2023, a student at a local performing arts school), while StageHands starts shaving precious seconds from the conversion.

“We have about two weeks,” said Van Rouwendaal, who is usually in Utrecht but is playing this year’s match at Basel.

“My company has about 13 Dutch people, 30 local boys and girls swaying it in Switzerland.

"In those two weeks, I had to figure out who fits in every job. Someone is good at running, some are good at lifting, and some are good at organizing backstage areas. It's kind of like being good at Tetris because you have to put everything in a small space in a perfect way."

After a song is over, the team is ready to roll.

In addition to the stage hands, there are also some people responsible for positioning the lights and setting up fireworks. During each show, the 10 cleaners swept the stage with mops and vacuum cleaners on the stage.

"My cleaners are just as important as the stage staff. You need a clean stage, but if there is an overhead shot of a person lying down, you don't want to see Shoeprints on the floor."

The focus on details is clinical. In the backstage, each performer has his own microphone stand set to the correct height and angle to ensure every performance is camera perfect.

"Sometimes the delegation would say the artist would want to wear another shoe for the finals," Van Rouwendaal said. "But if that happens, the microphone stands are in the wrong height, so we have a problem!"

SRG / SSR

SRG / SSRHowever, spontaneously changing footwear is not the worst problem he faces. In the 2022 competition in Turin, the stage is 10m (33 feet) higher than the backstage area.

As a result, they are pushing heavy stage props (including mechanical cattle) onto the steep ramp between each action.

"We were exhausted every night," he recalled. "This year was better. We even had an extra backstage tent in the place where we prepared the props."

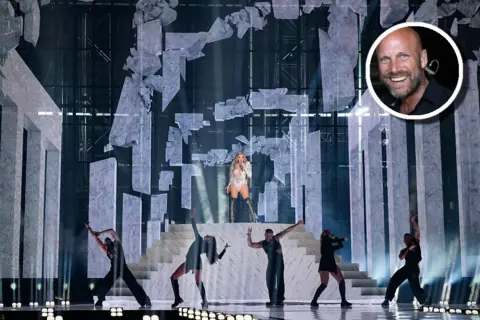

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProps are an important part of the European TV network. This tradition began with the second match in 1957, when Germany's Margot Hielscher sang part of her song Telefon, which Telefon entered (you guessed it) the phone.

In the following decades, phases became increasingly crafted. In 2014, Mariya Yaremchuk of Ukraine tied one of her dancers into a giant hamster wheel, and Romania performed well in 2017.

This year we have a disco ball, a space hopper, a magic food blender, a Swedish sauna and, for the UK, a fallen chandeliers.

"It's actually a huge logistics effort," said Damaris Reist, deputy director of the competition this year.

“It’s all organized in a circle.

"In the background, the used props are pushed back to the back of the queue, and so on. It's all planned."

"Smuggling Route"

During the show, there are several secret passages and “smuggling routes” that allow props to enter and exit the visual, especially when the performance requires new elements.

If you want, pull your mind back to Sam Ryder's performance in Italy's 2022 match.

There, he was alone on the stage, posting a pretend shot on his spinning jumpsuit, and suddenly, an electric guitar emerged from the thin air and fell into his hands.

Guess who put it there? Richard Van Rouwendaal.

"I'm a magician," he said with a smile. "No, no, no...that's a collaboration between the camera director, the British delegation and the stage staff."

In other words, Richard hid on the stage with a guitar in his hand while the director shot open the big shot, covering his presence among the audience at home.

"It's choreographed to the nearest millimeters," he said. "We're not invisible, but we have to be invisible."

Reuters

ReutersWhat if all this goes wrong?

Van Rouwendaal Reveeals will have some tips that will never be noticed.

If he announces headphones that are “stage unclear”, the director can buy time by showing the audience’s extended shots.

If a bigger event happens - "The camera can be destroyed, the props will fall" - they cut one of the hosts in the green room into minutes.

In the control room, the tape of the dress is played synchronously with the live performance, allowing the director to switch to pre-recorded shots in the event of a stage intrusion or a microphone malfunction.

However, visual failure is not enough to trigger spare tape, but as Switzerland's Zoëmë found in the first semifinals on Tuesday.

Her performance briefly broke when the cameras on the stage freeze, but the producer just cut into large shots until it was fixed. (If this happened in the final, she would have a chance to perform again.)

“In fact, there are many steps being taken to ensure that every behavior can be displayed in the best way,” Rice said.

“Some people know the regulations in their minds, they’re always going through what can happen and what they do in a variety of different situations.

“I’m going to sit next to our production supervisor and if there’s (in case) someone has to run, maybe it’s me!”

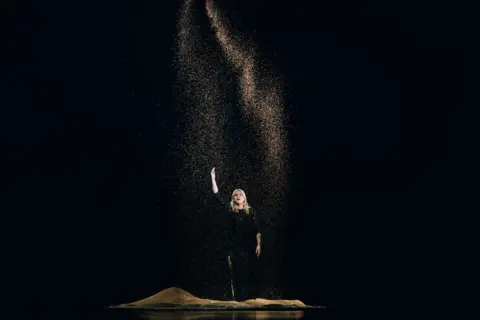

Sarah Louise Beannett

Sarah Louise Beannett Sarah Louise Bennett

Sarah Louise BennettIt is no surprise to learn that it is very stressful to have a three-hour live broadcast with thousands of moving parts.

This year, organizers have taken steps to protect the welfare of contestants and crew, including closed-door rehearsals, longer breakouts between shows and the creation of a “disconnected zone” that prohibits cameras.

Even so, Reist said she has been working every weekend for the past two months, and Van Rouwendaal and his team often pull 20 hours.

The transition was so long that in 2008, Eurovision production legend Ola Melzig built a bunker under the stage with a sofa, a "sadly unused" PS3 and two (yes, two) espresso machines.

"I don't have hidden luxury goods like Ola. I don't have that level yet!" laughed Van Rouwendaal

"But backstage, I'm with my crew. We have stroopwafels there and last week was King's Day in the Netherlands, so I baked pancakes for everyone.

“I tried to make it fun. Sometimes we went out to drink and cheer because we had a good time.

“Yes, we have to be at the highest level, we have to be as sharp as a knife, but it’s also important to have fun together.”

And, if everything is planned, you will see them this weekend.