“These,” Dr. Anas Holani said, “from the big grave of the mix.”

The head of the newly opened Syrian Identification Centre stood beside two tables, covered by the femur. Each laminated white tablecloth has 32 human thigh bones. They are neatly aligned and numbered.

Sort is the first task for this new link in a long chain from crime to Syrian justice. "The big mixed grave" means throwing the body on top of another.

The opportunity for these bones belongs to the killings of hundreds of thousands of the regimes believed to have been ousted President Bashar al-Assad and his father Hafez, who have jointly ruled Syria for more than fifty years.

If so, they were one of the most recent victims: They died no more than a year ago, Dr. Al-Hourani said.

Dr. Al-Hourani is a forensic dental doctor: teeth can tell you more about the body, at least when determining who the person is, he said.

But with the femur, lab workers in the basement of this grey office building in Damascus can start the task: they can learn height, gender, age, age, how they work; they may also see if the victim is tortured.

The gold standard for identification is of course DNA analysis. However, he said there is only one DNA testing center in Syria. During the Civil War, many people were destroyed. and “many precursor chemicals required for testing are currently not possible due to sanctions”.

They were also told that “a portion of the tool can be used for aviation and therefore for military purposes.” In other words, they can be considered "dual use", so many Western countries are prohibited from exports to Syria.

Additionally, the cost is: $250 (£187) per test. And, Dr. Al-Hourani said: "In a mixed mass grave, you have to do about 20 tests to collect all parts of a body". The laboratory relies entirely on ICRC funds.

The new government, whose Islamic rebels turned rulers, said their so-called "transitional justice" was one of their priorities.

Many Syrians who lost relatives and lost all traces told the BBC they still had no impression and frustration: they hoped more efforts from the people who caught up with the Bashar al-Assad from the war last December.

During the long conflict, thousands were killed and millions were displaced. Moreover, according to an estimate, 130,000 people were forcibly disappeared.

At the current rate, it will only take a few months to identify a victim from a mixed mass grave. "It will be years of work," Dr. Al-Hourani said.

The body was broken and tortured

11 of the "mixed mass graves" slipped around the beautiful barren hilltops outside Damascus. The BBC is the first international media to visit the website. The grave is now obvious. In the years since their excavation, their surfaces have sunk into dry stone lands.

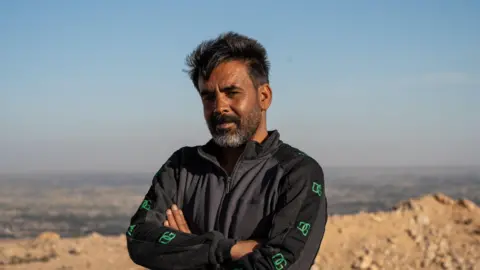

Accompanying us were Hussein Alawi al-Manfi or Abu Ali because he also called himself. He is the driver of the Syrian army. Abu Ali said: "My goods are human bodies."

The compact man paired with salt and pepper beards due to the relentless investigation by Syrian emergency official Syria and its advocacy group Syrian American executive director Mouaz Mustafa. He convinced Abu Ali to join us and witness what Mouaz calls "the worst crime of the 21st century."

Abu Ali transported the lord's body load to multiple locations for more than 10 years. At this location, at the beginning of the demonstration, he averaged twice a week, about two years, and then the war between 2011 and 2013.

Routines are always the same. He will go to military or security devices. "I have a 16 million (52-foot) trailer. It doesn't always fill the edges. But, I think, there are an average of 150 to 200 bodies per load."

In his cargo, he said he firmly believed in himself as a civilian. Their bodies are "blurred and tortured". The only sign he could see was the number written on the body or stuck on the chest or forehead. These numbers determine where they died.

He said that from the “215”, a notorious military intelligence detention center in Damascus was called “Branch 215.” This is where we will revisit in this story.

Abu Ali's trailer does not have a hydraulic lift to tilt and dump the load. As he retreated back to the ditch, the soldier pulled the body one by one into the hole. The front loader tractor then "flatten them, compress them in, fill the grave."

Three men from nearby villages arrived. They confirm the story of military vans’ regular visits to this remote area.

As for the person behind the steering wheel: How could he do this week after week, year after week? What was he telling himself whenever he climbed into a taxi?

Abu Ali said he learned to be a silent servant of the country. “You can’t say good or bad.”

When the soldiers dumped the bodies into freshly excavated pits, "I just walked away and looked at the stars. Or looked down at Damascus."

"They broke his arm and beat him on the back"

Damascus is where Malak Aoude returned after he recently worked as a refugee in Türkiye. Syria may have escaped the stifle of the Assad dynasty's dictatorship. Marak is still serving his sentence.

For the past 13 years, she has been locked in everyday pain and desire. In 2012, a year when some in Syria dared to protest against the president, her two boys disappeared.

Mohammed was still a teenager when he was drafted, as the regime's deadly suppression sparked a full-scale war as the demonstrations spread.

He hated what he saw, his mother said. Mohammed began to abscond and even attended the demonstration in person. But he was tracked.

"They broke their arms and knocked back his back," his mother said. "He stayed in the hospital for three days."

Mohamed went to AWOL again. “I report him missing,” Marak said. "But I hid him."

In May 2012, 19-year-old Mohammed ran out of luck. He was caught with a group of friends. They were shot to death. Marak said there was no formal notice. But she always thought he was killed.

Six months later, Mohammed's younger brother Maher was dragged out of the school by an officer. This is Mach's second arrest. He participated in the protest in 2011 at the age of 14. This led to his first arrest. A month later, when he was detained, he was wearing underwear and covering it, his mother said, among cigarette burns, wounds and lice. "He's scared."

Malak believes Maher disappeared from school in 2012 because authorities discovered she had been hiding his older brother. Now, for the first time in 13 years, Marak returns to that school, desperate to get any clues about what happened in Mach.

The new principal produced several abused red ledgers. Marak traces the line of his name with his fingers and then finds his son's name. The record notes flatly: December 2012: Maher was excluded from school because he failed to attend classes for two weeks.

There is no explanation that the country has disappeared. There are other things, though: the folder with Maher school records was found. Its cover is decorated with a photo of the wise Bashar al-Assad, staring carefully into the distance. Marak picked up a pen from the principal's desk and smeared it on the photo. Six months ago, the gesture could have been fatal.

The only residue Malak has to stick with over the years were two people who said they saw Maher in "Branch 215" - the same military detention center that caused so many carcasses for Abu Ali.

A witness told Marak that her boy told him something about his parents, and his mother said that only he knew. It's definitely him. "He asked this guy to tell me he did a good job." Malak exuded tears, stuffed with ragged tissues to the corner of her eyes.

For Marak, like many Syrians, Assad's fall was not only a happy day, but a day of hope. "I think Mach has a 90% chance of getting out of prison. I'm waiting for him."

But she couldn't even find her son's name on the prison list. Therefore, the painful th movement continued to move forward in her process. "I feel lost and confused," she said.

Her own brother Mahmoud was killed in 2013 by a tank fired by a civilian.

"At least he has a funeral."