Millions of people in the Los Angeles area are exposed to wildfire smoke as fires destroy homes and vehicles. Fires in January 2025 destroyed thousands of buildings, along with building materials, furniture, paint, plastics and electronics inside them.

When such materials burn, they release toxic chemicals that can harm people breathing the air downwind.

A 2023 study of smoke from fires at the wildland-urban interface (the area where urban communities bleed into wildland) found that it contains a host of chemicals harmful to humans, including hydrogen chloride, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins and a range of toxic organic matter. Compounds, including known carcinogens such as benzene, toluene, xylene, styrene and formaldehyde. Researchers also found metals in the smoke, including lead, chromium, cadmium and arsenic, which are known to affect multiple body systems such as the brain, liver, kidneys, skin and lungs.

The short-term effects of exposure to such smoke can trigger asthma attacks and lead to lung and heart problems.

But smoke can also have long-term effects that are not yet understood. As an environmental toxicologist who focuses on the health effects of wildfire smoke, many of my colleagues and I are increasingly concerned about the effects of long-term and repeated exposure to wildfire smoke that more people now face.

Long-term exposure to smoke is on the rise

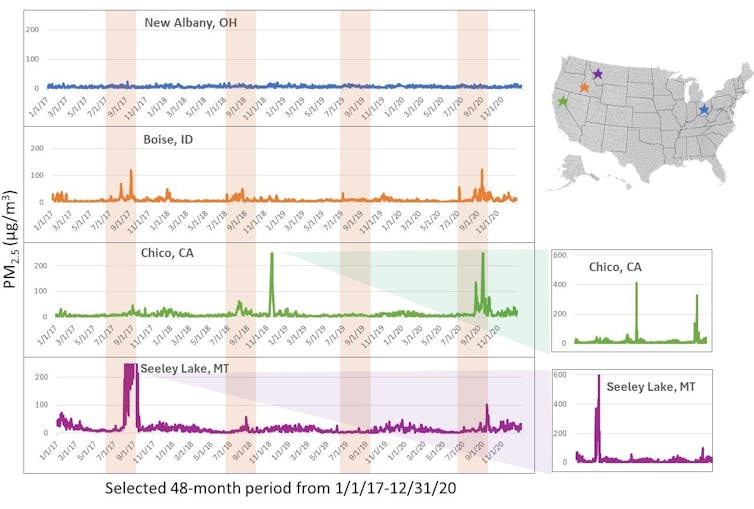

Nationally, the area burned by wildfires in the United States has nearly doubled every decade since 1990. This is changing how people are exposed to wildfire smoke.

Increasingly, communities find themselves shrouded in smoke for days or even weeks on end. In 2023, large-scale wildfires broke out in Canada, and thick smoke spread to many communities in the United States many times. Controlled burns set up by firefighters are meant to clear flammable brush and reduce the severity of future wildfires, but they also add smoke to the air.

Wildfire smoke is now a major source of PM2.5, tiny particles that can penetrate the lungs, in the western U.S.

This increased exposure increases the need to understand the long-term consequences of living and working in wildfire risk areas.

Dosage, duration and frequency are important

When scientists study the health risks of wildfire smoke, they tend to use analytical methods developed to assess the health effects of low-level, chronic urban air pollution exposure, such as vehicle exhaust or smokestack emissions. However, these methods fail to capture the dynamic and intense nature of wildfire smoke.

Researchers suspect that people exposed to different intensities and durations of smoke will experience different consequences. Repeated exposure to wildfire smoke can also have complex health effects over time.

To study the long-term effects of wildfire smoke, scientists need to know the amount, duration and frequency of people's exposure to smoke. This isn't an experiment that anyone could do on humans in a lab, but data can be collected from communities affected by wildfires.

However, such data collection is currently rare.

Most studies exploring long-term exposure, such as its effects on dementia or pregnancy, use average exposure data over many years rather than detailed exposure data.

Some people focus on specific events. For example, a study of residents exposed to smoke for six weeks during the 2017 Rice Ridge Fire near Seeley Lake, Montana, found that their lung function declined significantly for at least two years after the fire. It was a forest fire, and while burning vegetation is bad, it's generally considered less toxic than burning buildings.

Thinking differently about smoke exposure

Improving understanding of the long-term effects of wildfire smoke requires thinking about smoke differently.

If epidemiologists can begin to clearly define the negative health effects of wildfire smoke exposure in terms of dose, duration, and frequency in studies, taking into account dynamics and sporadicity, then toxicologists can test these in humans in animal experiments. Modeling experience.

These experiments will have the potential to improve understanding of long-term health risks and then help scientists develop effective guidelines and strategies to mitigate harmful exposures.