On the remote Tibetan Plateau, a rare fungus grows inside dead caterpillars. In traditional Chinese medicine, this parasitic fungus is prized for its purported medicinal properties. called Cordyceps sinensis – Colloquially known as cordyceps or “Himalayan gold” – it can fetch astronomical sums on the herbal market: up to $63,000 per pound.

Cordyceps sinensis The fungus is a parasite that targets caterpillars, which are the larvae of the ghost moth. The process begins in late summer to early fall, when fungal spores infect the caterpillars. Over time, fungal filaments called mycelium slowly spread, eating the caterpillars from the inside, and by winter they turn into a hard, mummified shell. When spring arrives, the fungus enters its final stage: a grass-like fruiting body sprouts from the preserved caterpillar's head and protrudes from the soil.

While many traditional Chinese medicine/herbal medicine consumers are attracted to this fungus for its purported health benefits, my interest lies in the dark side of its harvest: the deadly relationship between cordyceps harvesting and lightning strikes. As a meteorologist, I study lightning and its effects around the world. A combination of factors makes the situation on the Tibetan Plateau so dangerous.

deadly harvest

People look for this fungus in late spring and summer, when lightning strikes are most common in these mountains. Villagers often spend weeks searching for this valuable resource in the rugged mountains, sometimes as high as 16,400 feet (5 kilometers) above sea level. That's over 3 miles of altitude.

At this altitude, the weather can change rapidly and there is no safe place to hide from the storm. While the area doesn't see as many lightning strikes as some parts of Asia, it's still dangerous enough to pose a serious threat during these critical harvest months.

Tragically, cordyceps hunting has resulted in at least 31 deaths and 58 injuries from lightning strikes over the past decade, according to data from the China Meteorological Disaster Yearbook and government websites such as the China Meteorological Administration. and China National Disaster Reduction Center.

In May 2022, seven Chinese villagers, including a young child, were struck and killed by lightning while picking fungi. The following year, three people from Nepal were injured by lightning while collecting fungi and had to be rescued by helicopter after being stranded in the mountains for several days.

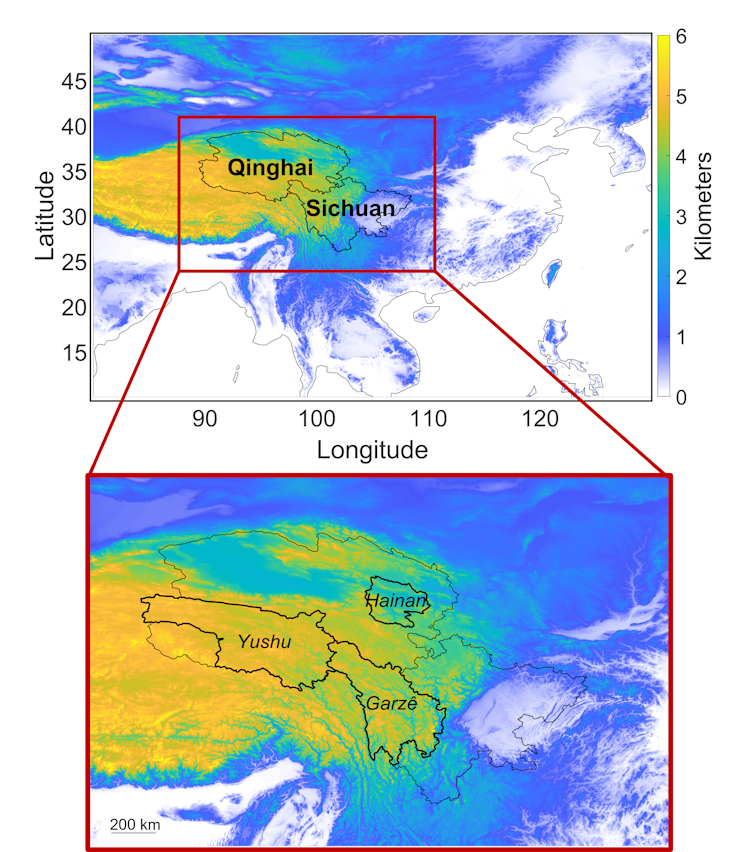

In our recent research, my colleague Ronald Holle and I found that the population-weighted lightning mortality rate in the fungus-collecting hotspots of Yushu and Garze counties in Sichuan Province, China, was staggering—10 to 20 times higher than in other areas. . Interest rates in China as a whole have risen. These figures are comparable to some of the most lightning-prone areas in Africa, where there is little lightning protection infrastructure or safety education.

But lightning isn't the only threat these villagers face on the mountain. They may encounter severe weather such as hail, heavy rain, and strong winds. The complex terrain makes weather patterns very dramatic and unpredictable. To make matters worse, cell phone signal and other communication options are limited or non-existent, leaving villagers unable to receive weather disaster warnings.

They may also face threats from wild animals and dangerous slopes. In one tragic case, a collector was struck by lightning and fell to his death on steep terrain. Access to medical care is limited. When an accident occurs, it can take several days for rescuers to arrive.

Why take this risk?

It all comes down to the high-risk, high-reward nature of cordyceps harvesting.

For local villagers, the potential rewards from harvesting cordyceps are huge. With limited income opportunities in this remote region, many see the fungus trade as their best hope for survival. They face a difficult choice: risk their lives or fall into poverty.

Improving lightning safety education and infrastructure is important, but it won’t be easy. Any real change requires significant investment.

While local governments do organize some lightning safety education, these mountain communities are isolated and the information is often out of date. And there is simply no practical way to install adequate lightning protection in the vast and rugged terrain where fungi are collected.

fragile pursuit

The environment is suffering too. So many people seek out the fungus that they destroy fragile mountain soil, cut down trees for firewood, and leave trash in campsites.

Years of overharvesting forced foragers to spend more time in the mountains searching for enough fungi, increasing their chances of being struck by lightning and causing fungal populations to decline. Scientists warn that if this aggressive logging continues, the fungus could disappear entirely within the next few decades.

Maybe there is some hope. Researchers are exploring ways to cultivate the fungus as a possible alternative to wild-harvested varieties. Meanwhile, the governments of China, India, Nepal and Bhutan have implemented regulations to protect the sustainability of cordyceps.

But any solution will need to address the underlying economic and educational inequalities in this remote region and provide these communities with new livelihood opportunities so they don’t need to risk their lives chasing “Himalayan gold.”