Have you ever found yourself in the museum’s gallery of Human Origins, staring at a glass box filled with rocks marked “Stone Tools” and murmured under your breath, “How did they know this is not just any old rock?”

At first glance, this seems impossible. But as an experimental archaeologist with more than a decade of experience in researching and manufacturing stone tools, I can say there are some obvious signs that humans or our very old ancestors have modified a rock.

This process, known as flintknapping, can be attributed to mastering force, angle, and rock structure. After being done correctly, FlintKnapping creates a recognizable feature that archaeologists use to identify stone tools.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8lwaebacxw[/embed]

Why are stone tools important?

A stone tool is a rock that has been selected for use or intentionally changed. The technology emerged about 3.3 million years ago and is crucial to human proteins - all living things and extinct species that belong to the human lineage. Currently, we Homo sapiens He is the only person himself.

But we are not the only creatures that make and use stone tools - many other primates will do - but humans modify their unparalleled extent in the animal kingdom. Monkeys and other apes can hold a large stone in their hands to crack nuts on flat, plain stones.

But most humans do not rely on the stones collected. They modify it and shape it into useful tools for various tasks, including meat cutting or planting, carpentry, scratching skins, and even projectiles.

Stone tools are important to archaeologists because they are durable and well preserved. This makes them some of the best evidence for human behavior and allows us to better understand how different populations adapt to local environments in time and in large geographic regions.

How are stone tools made?

Humans produce stone tools by breaking or wearing rocks. Here I will focus on cracked or peeled stone techniques, as tools made through this technique dominate the archaeological record.

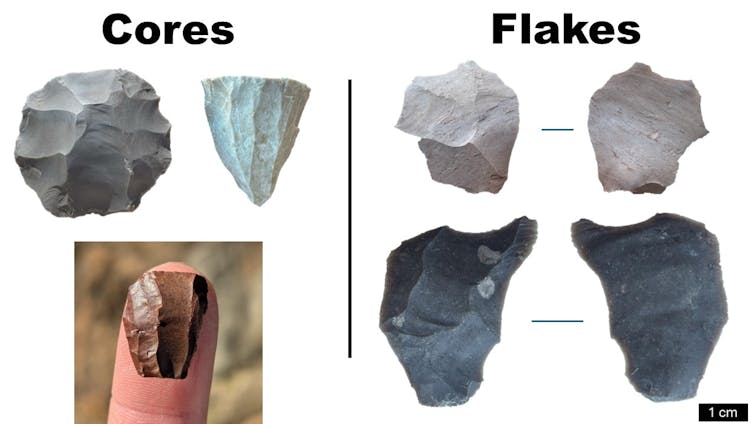

The process of peeling involves applying force to the edge of the stone through a percussion instrument or pressure, called a striking platform, to remove part of the rock, which is called flakes. Guided by teachers and a lot of practice, Flintknappers can learn how to identify promising platforms on a stone known as the core and remove sheets from them all the time. When hit, the platform will be removed from the core and is a key feature of the flake.

The sheets provide a sharp tip immediately. FlintKnapper can also further modify them to more specific shapes for other purposes. An iconic example is the hand axe, which is the core that is peeled off into the shape of a teardrop.

We often use Hammerstones or large pieces of antlers called billets to hit the edge of the core. Repeated flaking not only allows FlintKnappers to produce a large number of sharp tips in the form of flakes, but also allows them to shape the core into the form they want…often at the risk of personal injury along the way. My fingers can prove this!

However, not every type of rock needs to peel off the features into the tool. You want the stone to show what is called a bone fracture. If you've ever seen a glass rest, you've witnessed a bone fracture. This smooth fracture has concentric wave-like ripples defined by the physics of how forces move through different materials.

When experienced knives are ready to remove the flakes, we understand how the material we work on when we are impacting will break in order to predict the shape and size of the tools we produce. Stones like obsidian like volcanic glass are posters with bone fractures.

Of course, there are many variations in the quality of rocks used by humans to make stone tools, and many people use lower-quality stone. Even some of the earliest tool manufacturers preferred rocks of certain characteristics, such as durability.

How do you identify stone tools?

You may hear people say that the rocks they find in their gardens are tools because they are "completely fit in the hand" or "tool-shaped". But it's not that simple. Although shape and function may play a role in the end product of stone tools, it is not a smoking gun.

Archaeologists can determine that a rock is a stone tool based on clues left from the process of a conjunctival fracture during flintknapping.

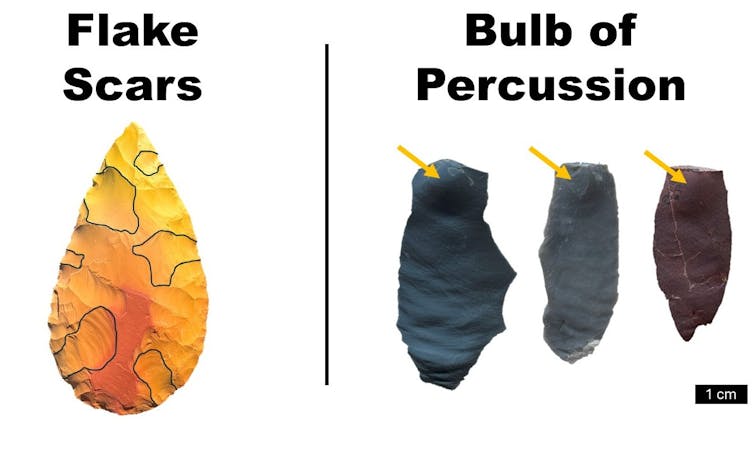

Such clues are the presence of flake scars, or what we call negative removal, which can be found on both the core and the flakes. These have characteristic ridges on one or more sides of the rock that outlines the previous sheet removal, thus using the term scar.

When we see multiple sheet-like scars consistent in their orientation and size rather than random scars, this is likely to be deliberately processed by humans.

The second function is what we call percussion balls. This is the bulge of the sheet, just below the eye-catching platform, which is generated by the force concentration when the knapper hits the force.

Given that the percussion that produces a light bulb requires hitting the rock at a specific angle and disengages from the stone with enough force, this is impossible to create through natural processes, but not impossible. Scientists have even discovered naturally occurring stone fragments or natural bacillus in Antarctica.

However, when many sheets with these diagnostic features are found, they are unlikely to be created naturally.

The last thing to consider when determining whether a rock is a stone tool is to find its background. Are there many of the characteristics that stones look for in the area when trying to identify stone tools? Are stone tools made of exotic materials, or are they like the rest of the nearby rocks?

If you find a lot of stone tools in the same area made of one rock, you might stumble upon an old Flintknapping workshop. But if you find a tool made of a stone that can only be found hundreds of miles away, maybe someone trades it with this material or takes it with you.

Try it yourself

I think the best way you can learn to identify if a stone is a tool or just a stone is to try yourself. I've taught over 100 people of all ages to make stone tools, and most agree: It's harder than you think.

This experience brings you into the minds of our ancestors, trying to solve one of the earliest problems our lineage faces: gaining a sharp advantage from a chunky rock.