British Broadcasting Corporation

British Broadcasting CorporationWe are now in the age of diet pills.

Decisions about how to use these drugs may affect our future health and even the face of our society.

And, as the researchers found, they have debunked the belief that obesity is simply a moral flaw of the weak-willed.

Diet pills have become the centerpiece of the national debate. This week the new Labor government said they could be a tool to help obese people in England get off benefits and back into work.

This statement and the reactions to it reflect our personal views on obesity and what should be done to address it.

Here are some questions I want you to think about.

Is obesity something people bring on themselves and they just need to make better life choices? Or is this a social failure, the millions of victims of which require stronger laws to control the types of food we eat?

Are effective weight-loss drugs a wise choice in the obesity crisis? Are they being used as a convenient excuse to avoid the big question of why so many people are overweight?

Personal choice vs. the nanny state; realism vs. idealism—few medical conditions inspire such heated debate.

I can't answer all of these questions for you - it all depends on your personal views on obesity and the type of country you want to live in. But when you think about these issues, there are some further things to consider.

Unlike conditions like high blood pressure, obesity is highly visible and has long been associated with a stigma of blame and shame. Gluttony is one of the seven deadly sins of Christianity.

Now, let's look at semaglutide, which is marketed under the brand name Wegovy and is used for weight loss. It mimics a hormone released when we eat, tricking the brain into thinking we are full, reducing our appetite and thus eating less.

Professor Giles Yeo, an obesity scientist at the University of Cambridge, said this means changing just one hormone "can suddenly change your entire relationship with food".

This has all sorts of implications for the way we think about obesity.

Professor Yang believes that this also means that many overweight people have "hormonal deficiencies, or at least hormone levels are not that high", which makes them physiologically more hungry and more likely to gain weight than people at their natural weight. Thin.

This may have been an advantage 100 years ago or earlier, when food was less plentiful - prompting people to consume calories while they were available because tomorrow they might not be available.

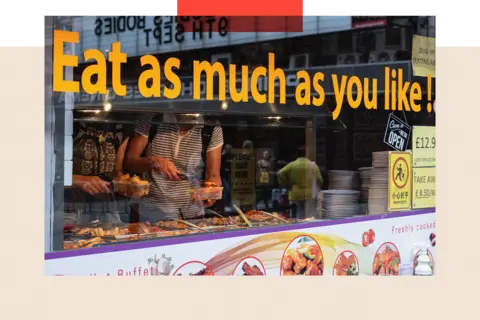

Our genes haven't changed profoundly in a century, but we live in a world where, with the rise of cheap and high-calorie foods, the expansion of portion sizes, and towns that make it easier to drive than to drive, it's easier to lose weight Increase. Walk or bike.

These changes, which began in the second half of the 20th century, created what scientists call an "obesogenic environment," an environment that encourages unhealthy eating and lack of exercise.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne in four adults in the UK is now obese.

Wegovy can help people lose about 15% of their starting weight before benefits plateau.

Although often labeled a 'slimming pill', it can reduce weight from 20 stone to 17 stone. Medically, this will improve health outcomes in areas such as heart disease risk, sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes.

But Dr Margaret McCartney, a GP in Glasgow, warned: "If we continue to expose people to obesogenic conditions we will only permanently increase the demand for these drugs."

Currently, the NHS scheme only prescribes the drug for two years due to cost reasons. evidence shows When the injections stop, appetite returns and weight returns.

Dr McCartney said: "My biggest concern is that there is no focus on how to stop people from becoming overweight in the first place."

We know the obesity environment starts early. one fifth Children are already overweight or obese when they start school.

We know it affects poorer communities (where 36% of adults Obesity rates are higher in England (20%) than in more affluent areas, partly due to a lack of cheap, healthy food in those less affluent areas.

But there is often a tension between improving public health and civil liberties. You can drive, but you must wear a seat belt; you can smoke, but you pay a high tax and there are restrictions on age and where you can smoke.

So here are some further things for you to consider. Do you think we should also address the environments that lead to obesity, or just treat people when their health starts to suffer? Should the government get tougher on the food industry and change what we can buy and eat?

Should we be encouraged to go to Japan (a rich country with low obesity rates) and eat smaller, more frequent meals based on rice, vegetables and fish? Or should we limit the calories in ready meals and chocolate bars?

What about a sugar tax or a junk food tax? What about a broader ban on the sale or advertising of high-calorie foods?

Professor Young said that if we want change, then "we're going to have to compromise in some areas, we're going to have to lose some freedoms", but "I don't think we've made that decision within society, I don't think "I think we've debated that."

In the UK, there is an official obesity strategy - 14 of them span three decades But there's little to show for it.

These include five-a-day campaigns to promote eating fruit and vegetables, highlighting calorie content on food labels, limiting the promotion of unhealthy foods to children, and voluntary agreements with manufacturers to reformulate foods.

Despite early signs of childhood obesity in UK may start to declinethese measures have not fully changed the national eating habits and reversed the obesity trend as a whole.

There's an idea that diet pills may even be the event that triggers changes in our diets.

"Food companies make money, that's what they want - my only hope is that if diet pills help a lot of people resist buying fast food, could that start to turn some of the food landscape around?" Professor Navid Sattar of the University of Glasgow asked.

As weight-loss drugs become more readily available, the question of how to use them and how they fit into our broader approach to obesity needs to be addressed quickly.

For now we're just dipping our toes in the water. The supply of these medicines is limited and because of their high cost, the NHS can only provide them to relatively few people and only for a short period of time.

This situation is expected to change dramatically over the next decade. With new drugs like tilsiparatide on the horizon, drug companies will lose legal protection — patents — meaning other companies can produce their own, cheaper versions.

In the early days of blood pressure medications or cholesterol-lowering statins, they were expensive and only available to the few who would benefit most. Around 8 million people in the UK are now taking these drugs.

Professor Stephen O'Rahilly, Director of the MRC's Metabolic Diseases Unit, said blood pressure could be tackled through a combination of medicines and social change: "We screened for blood pressure, recommended lower sodium (salt) content in food and developed a cheap, safe and effective Antihypertensive drugs.”

It's similar to what's happening with obesity, he said.

It's unclear how many of us will end up taking weight-loss drugs. Is it only for those who are very obese and have medical risks? Or will it be a preventative measure to stop people becoming obese?

How long should people take weight loss pills? It should be a lifetime, right? Should they be widely used in children? Does it matter if people on these drugs still eat unhealthy junk food, just less of it?

How quickly should weight loss medications be taken when we don’t yet know the side effects of long-term use? Is it acceptable for healthy people to take them solely for cosmetic purposes? Does their presence secretly widen obesity and health gaps between rich and poor?

So many questions, but so far, no clear answers.

"I don't know where it will land - we are on a voyage of great uncertainty," said Professor Navid Sattar.

Above: Getty Images

BBC in-depth report is the new home of websites and apps delivering the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a unique new brand, we'll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and in-depth coverage of the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. We'll also be showcasing thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We start small but think big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.