From the time you wake up in the morning to the time you go to bed at night, and even while you're sleeping, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency affects your life. The air you breathe, the water you drink, the chemicals under your sink, the car you drive, the products you buy, the food you eat and a host of daily routines all depend on the agency and the EPA administrator (the equivalent of the Cabinet) Action Secretary.

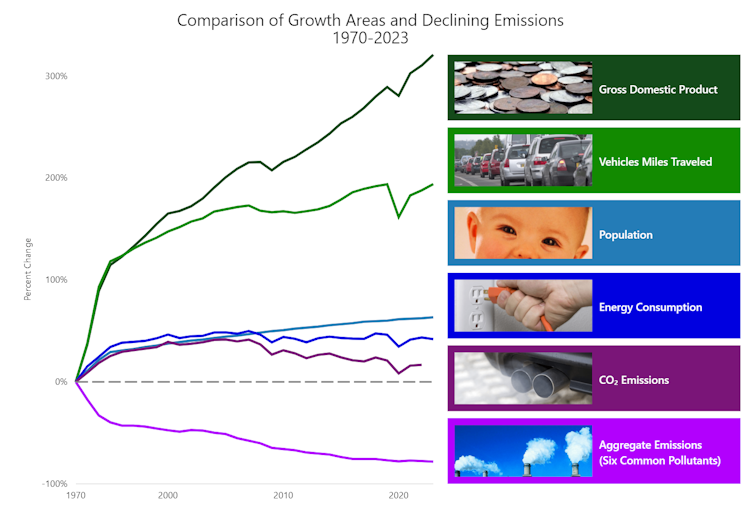

Since President Richard Nixon created the EPA in 1970, the U.S. population has grown 62 percent and gross domestic product has more than quadrupled. Americans now drive nearly three times as many miles as before and consume almost 50% more energy.

However, traditional air pollution emissions fell by 78%. Lakes and rivers are cleaner, chemicals are safer, and hazardous waste from past industrial activities is cleaned up. This record shows that a clean environment can be compatible with economic growth.

Still, opinions about the EPA tend to be highly polarized. Environmentalists say the agency is moving too slowly. Conservatives, meanwhile, accuse it of regulatory overreach. The EPA administrator’s job is to embody America’s commitment to a clean and healthy environment, but the role has always been controversial — perhaps now more than ever.

regulators and scientists

EPA is the federal government's largest independent regulatory agency, with approximately 16,850 employees and an annual budget of approximately $10 billion. The agency also received about $100 billion in special funding through the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 — at least some of which President-elect Donald Trump said he hopes Congress repeals bill.

Although the EPA is headquartered in Washington, D.C., it is a very decentralized agency. Nearly half of its employees work in 10 regional offices across the country, led by political appointees who report directly to the chief executive.

Other employees work at centers in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, as well as in laboratories across the country. EPA scientists support the agency's standard-setting efforts and assist in identifying and pursuing violations of environmental laws.

Of the EPA's 16 managers, nine are attorneys, two are former governors, five are former state environment secretaries, and four held lower-level EPA positions earlier in their careers. These contexts highlight that the agency's powers are based on interpreting and applying environmental law and that doing so requires sound political judgment.

Regulation and Litigation

EPA's work is driven by major U.S. environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. Most were enacted between 1969 and 1990, with some significant revisions since then.

These regulations are highly prescriptive and set goals and deadlines, effectively defining much of EPA's agenda. They vary in the extent to which they prohibit, permit, or require agencies to consider compliance costs to regulated entities.

Most laws include broad citizen suit provisions that allow businesses and environmental groups to file lawsuits at any time in court to challenge EPA actions or urge the agency to take more action and move faster. Both Republican and Democratic EPA managers have noted that their priorities may be boosted by court orders that require the agency to comply with legal deadlines but are unable to meet the requirements.

Even the most detail-oriented Congress does not have the expertise or institutional capacity to specify every step needed to achieve environmental goals. Environmental law assigns this responsibility to the EPA. Agency officials develop implementing regulations in accordance with the rulemaking process set forth in federal administrative law.

The EPA continues to be sued over these laws and regulations. Cases often focus on whether the statute actually contains the authority claimed by the agency. It is no accident that key concepts in administrative law are elaborated and argued in environmental cases.

A classic example is “Chevron deference”—the principle that, when faced with legal ambiguity, courts should defer to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of the law relevant to its work. Chevron's deference stems from a 1984 Clean Air Act case; in 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court slashed it. The ruling could seriously damage the EPA's future work.

The EPA's actions are frequently challenged by the Supreme Court. Recently, judges have limited the agency's authority on issues such as greenhouse gas emissions and wetland protection.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bADDPJ0T_w[/embed]

working with states

While the EPA has direct authority to enforce federal laws and regulations, most regulations place state environmental agencies in charge of the day-to-day work of issuing permits and enforcing laws. EPA delegates this authority to states, provided that states have sufficient legal authority and resources to carry out this work and oversee their activities.

EPA also provides major funding to states, including operating appropriations totaling approximately $1.2 billion in fiscal 2024, and wastewater and drinking water infrastructure capitalization appropriations totaling approximately $3.4 billion during the same 12-month period.

Finally, the EPA plays an important role in responding to emergencies, such as the 2008 release of millions of tons of coal ash into the Embry and Tennessee rivers; the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico; and the 2023 East Palestine, Ohio train derailments and chemical spills; and every major hurricane or extreme weather event. The agency's emergency response efforts focus on monitoring air and water pollution, cleaning up oil and chemical spills and helping restore water and sewer infrastructure.

Don't expect to be popular

In addition to its interactions with the courts, the EPA has received considerable attention from Congress. Fifty-one congressional committees and subcommittees have jurisdiction over various aspects of EPA, and the Government Accountability Office and EPA's own Inspector General regularly review the agency's work.

Administrators' decisions and public statements have important implications for regulated industries and communities affected by pollution and toxic exposure. The EPA is under constant pressure from large and powerful interest groups and must balance those pressures in myriad ways—ideally, while upholding the policies outlined by the agency's first administrator, William Ruckelshaus. Core Values: Obey the law, follow science and be transparent.

Over the agency's 54-year life, nearly all administrators have taken that responsibility seriously, even if it put them at odds with other agencies and sometimes the president. Running the EPA is not for someone who wants to be politically popular or make everyone happy.

Nonetheless, administrators play a critical role in maintaining the quality of life that Americans now expect from their government to ensure and preserve for generations to come.

This story is part of a series of profiles on cabinet and senior executive positions.