As Donald Trump's second inauguration approaches, concerns that he threatens American democracy are rising again. Some of the warnings cited Trump's authoritarian rhetoric, his willingness to undermine or denigrate institutions designed to limit any president, and his combative style of trying to expand executive power as much as possible.

Authoritarianism erodes property rights and the rule of law, so financial markets often sound alarm at political unrest. If major investors and businesses truly believed that the United States was on the verge of a dictatorship, there would be massive capital flight, a sell-off in stocks, a surge in U.S. credit default swaps, or a rise in bond yields that would not be possible with typical macroeconomic factors such as inflation forecasts to explain.

On the contrary, there are no systemic signs of such a market reaction, and no investors have left U.S. markets. Quite the opposite.

This lack of panic does not prove that democracy is ever safe, nor does it prove that Trump is fundamentally incapable of harming American democracy. But it does suggest that the credible institutions and investors who actually make a living betting on political outcomes do not believe that a dictatorship in the United States is imminent or even likely.

This may be because subverting the machinery of American democracy requires overcoming numerous constitutional, bureaucratic, legal, and political hurdles. As a political economist who has written extensively about the constitutional foundations of modern democracies, I think it's more complicated than one person issuing a reckless executive order.

Presidents have long had more power

Throughout U.S. history, presidents have expanded executive power to a much greater extent than Trump achieved in his first term.

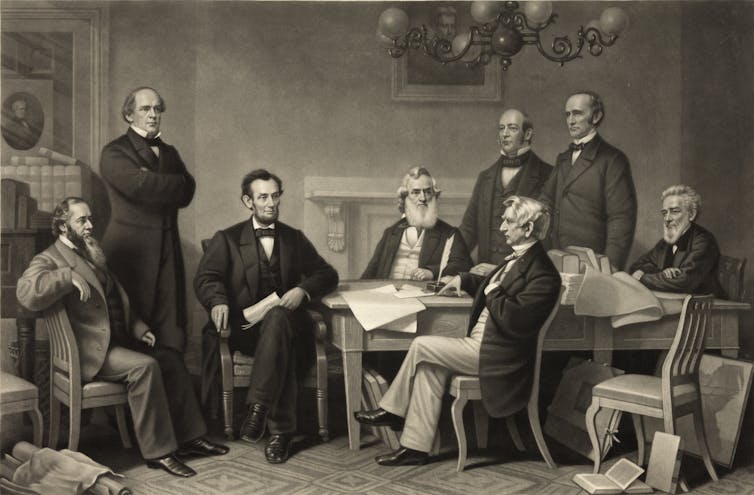

Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War, allowing detention without trial. He bypassed Congress with sweeping executive actions, most notably the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared slaves free in Confederate states.

During World War I, Woodrow Wilson created the executive branch and implemented draconian censorship through the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

Franklin Roosevelt's court-packing plan failed, but still scared the Supreme Court into submission. His New Deal bureaucracy concentrated enormous power in the executive branch.

Lyndon B. Johnson secured the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which transferred major war powers from Congress to the president. Richard Nixon invoked executive privilege to order secret bombings in Cambodia, steps that largely circumvented congressional oversight.

After 9/11, George W. Bush expanded executive privilege through warrantless wiretaps and indefinite detention. Barack Obama has been criticized for the dubious legal basis behind drone strikes targeting U.S. citizens deemed overseas enemy combatants.

However, these historical examples should not be confused with the actual ability to impose one-man rule. The United States, however imperfect, has a deeply layered system of checks and balances that has repeatedly stymied presidents of both parties when they tried to govern by fiat.

Trump’s openly combative style is in many ways less adept at consolidating presidential power than many of his predecessors. During his first term, he communicated his intentions so transparently that he inspired numerous institutional forces—judges, bureaucrats, state officials, inspectors general—to resist his attempts. While Trump’s rhetoric has been more inflammatory, other presidents have taken greater caution in achieving deeper executive branch expansion.

Trump’s plan for January 6 was never realistic

Trump’s failure to impose his will became particularly evident on January 6, 2021, when talk of an impending “automatic coup” never translated into real-world mechanisms that would Keep him in office after his term ends.

Even before the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022 brought greater clarity to the process, scholars agreed that the Vice President's role in certifying elections was purely ministerial under the Twelfth Amendment, making him There is no constitutional basis for replacing or discarding certified electoral votes. Likewise, state law makes certification a mandatory ministerial duty, preventing officials from arbitrarily refusing to certify election results.

If Pence refuses to certify the Electoral College count, a court is likely to quickly order Congress to proceed. Moreover, the 20th Amendment sets noon on January 20 as the end day of the outgoing president’s term, making it impossible for Trump to remain in power simply by creating delays or chaos.

The idea that Pence's refusal to certify could eliminate state-certified votes or force Congress to accept a replacement slate has no solid basis in law or precedent. After January 20, the outgoing president will no longer be in office. Therefore, the chain of events required for an automatic coup to occur in 2021 may collapse under the weight of established procedures.

huge bureaucracy

The potential avenues for consolidating power in Trump's upcoming second term are equally narrow. The federal bureaucracy makes it difficult for the president to rule by fiat.

The Justice Department alone has approximately 115,000 employees, including more than 10,000 attorneys and 13,000 FBI agents, most of whom are career civil servants protected by the Civil Service Reform Act and whistleblower laws. They have their own professional standards and can challenge or expose political interference. If the government tried to clear them all out, it would encounter a protracted appeals process, legal restrictions, the need for a lengthy series of background checks, and a significant loss of institutional knowledge.

Past events, including the politically motivated firings of U.S. attorneys by the George W. Bush administration in 2006 and 2007, show that congressional oversight and internal department practices can still generate significant pushback, resignations and scandals that hamper scrutiny of the Justice Department political intervention.

Independent regulators have also resisted the president's dominance. Many committees are designed so that three-fifths of the committee members cannot belong to the same political party to ensure a certain degree of bipartisan representation. Minority commissioners can use a range of procedural tools — delaying votes, requiring full studies, holding hearings — to slow down or block controversial proposals. This makes it more difficult for a single leader to implement policies unilaterally. These minority commissioners can also alert the media and Congress to suspicious behavior, inviting investigation or public scrutiny.

Additionally, a 2024 Supreme Court ruling shifts the power to interpret federal laws passed by Congress away from executive branch government agencies. Federal judges now take a more active role in determining the meaning of congressional speech. This requires agencies to operate within a narrower scope and provide stronger evidence to justify their decisions. In effect, governments now have less room to stretch regulations for partisan or authoritarian purposes without encountering judicial resistance.

Defense layers

There are fragility in American democracy, and other democracies have collapsed under the rule of powerful executives before. But in my view, it is unreasonable to draw clear lessons from a small number of extreme outliers, such as Hitler in 1933, or the handful of elected leaders who have recently staged car coups in fragile or developing democracies such as Argentina, Peru, and Turkey. people. Even Hungary.

The United States stands out for its complex federal system, entrenched legal practices, and multiple layers of institutional friction. History has shown that these protections are effective in limiting presidential overreach—whether subtle or over-the-top.

Additionally, state-level politicians, including attorneys general and governors, have repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to challenge federal overreach through litigation and non-cooperation.

The military's professional culture of civilian control and constitutional loyalty, consistently supported by the courts, provides another safeguard. For example, the 1952 Supreme Court decision in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer overturned President Harry Truman's order that the military seize private steel mills to ensure supplies during the Korean War.

All of these institutional checks are further supported by strong civil society, which can mobilize legal challenges, advocacy campaigns, and grassroots resistance. Businesses can exert economic influence through public statements, campaign funding decisions and policy stances — as many did after Jan. 6.

Taken together, these overlapping layers of resistance make the path to dictatorship more challenging than many casual observers imagine. These protections may also explain why most Americans feel resigned to a second Trump term: Many may have realized that the nation’s democratic experiment is not threatened — and probably never has been.