Australian correspondent

Emma Teni, holding a pair of bright pink tweezers, wrestled a large, long-legged spider in a small plastic pot.

"He's posing," it lifted backwards as Spider Guardian joked. That's exactly what she's trying to achieve - so that she can use a small pipette to absorb the venom from her fangs.

Emma works from a small office called a spider milking room. On a typical day, she cows-or extract venom from 80 of them Sydney funnel spiders.

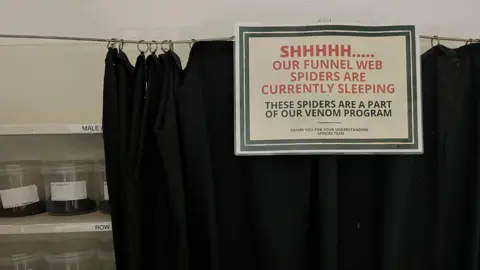

Among the three of the four walls, floor-to-ceiling shelves are piled with spiders with black curtains to keep them calm.

The remaining wall is actually a window. Through it, a little kid stares at Ms. Teni’s work, both fascinating and frightening. They hardly knew that the palm-sized spiders she was dealing with could kill them in minutes.

Emma actually said: "Sydney funnel - arguably the deadliest spider in the world."

Australia is famously filled with this deadly animal - This room at Australian Reptile Park plays a crucial role in the government's anti-venom program, which saves life on a continent and often jokes that everything wants to kill you.

"Spider Girl"

While the fastest death rate in the Sydney funnel is the 13-minute toddler, the average is close to 76 minutes - First aid provides you with a better chance of survival.

Since its inception in 1981, the anti-venom program at Reptile Park in Australia has been so successful that no one has been killed.

However, the program relies on the public to capture spiders or collect egg sacs.

In a van with giant crocodile stickers, Ms Tenny's team drove in Australia's most famous city every week, picking up the Sydney funnel, the loopholes have been handed over at descent points such as local veterinary practice.

She explained that these spiders are so dangerous for two reasons: Not only are their venom very effective, but they also live only in densely populated areas where they are more likely to encounter humans.

That's what the handyman Charlie Simpson is. He moved into his first home with his girlfriend a few months ago, and the keen gardener had found two Sydney funnels. He brought the second spider to the vet, and Ms. Teni picked it up shortly afterwards.

"I was wearing gloves at the time, but in fact, I should have worn leather gloves because their teeth are so big and strong," the 26-year-old said.

“I (just think) I’d better catch it because I’ve been told you’re going to bring them back to milk because it’s so critical.”

He joked, “This can solve my fear of spiders.”

When Ms. Teni unloaded a spider web delivered to her in a vegetarian jar, she stressed that her team did not tell Australians to go find the spider and “put themselves in danger.”

Instead, they ask if someone encounters one, they will safely capture it instead of killing it.

“It’s counterintuitive to say that it’s the deadliest spider in the world and then (asking the public) to catch it and bring it to us,” she said.

"(But) Now, the spider is there, thanks to Charlie, will… effectively save someone's life."

All spiders collected by her team were taken back to the Australian Reptile Park, where they were sorted, sorted by sexually and stored.

Any female who has been revoked is considered for breeding programs, which helps supplement the number of spiders donated by the public.

Meanwhile, males are six to seven times more toxic than females, Emma explains, and is used in anti-venom programs, milking every two weeks.

The pipette she uses to remove venom from the fangs is connected to the suction hose - crucial for collecting as much venom as each spider provides only a small amount.

While a few drops are enough to kill, scientists need to milk 200 spiders, enough to fill a bottle of anti-toxic agent.

Emma is a marine biologist who never thought of spending daily milking. In fact, she started using Navy SEALs.

But now she has no choice. Emma loves all the things about spider webs and uses various nicknames - Spider-Man, Spider-Mom, and even "Freaks", just as her daughter calls her.

Friends, family and neighbors rely on her to get to know Australia's creepy creepers.

Emma joked, “Some girls come home at the doorstep.” “It’s not uncommon for me to go home with a spider in the jar.”

The best place to get bitten?

Spiders represent only a small part of what Australian Reptile Park does. It has also provided snake venom to the government since the 1950s.

According to the World Health Organization, as many as 140,000 people die each year from snake bites, and many are triple the size of people with disabilities.

However, in Australia, these figures are much lower than that: between one and four people per year due to its successful anti-venom program.

Park operations manager Billy Collett took a Brown Snake from his locker and brought it to the table in front of him.

He held his head with his barefoot hand and placed his chin on the shooting glass covered with plastic wrap.

"They are very biting, but once you walk away you'll see it gushing out of the fangs," Mr Collett said.

"It's enough to kill us all in the room five times- maybe more."

Then, he turned to a more reassuring tone: "They are not looking for biting. We are too big, they don't want to eat; they don't want to waste venom on us. They just want to be alone."

He added: “To be bitten by a venomous snake, you have to really annoy it, cause it.

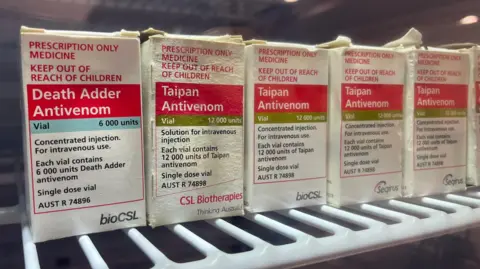

There is a refrigerator around the corner of the room where there is the original venom collected from the original venom. It was full of vials marked "Death Adder", "Taipan", "Tiger Snake" and "Eastern Brown".

The last of these is the second most venomous snakes in the world and the one that is most likely to bite you in Australia.

The venom was freeze-dried and sent to CSL Seqirus in Melbourne labs, where it turned into an antidote that could take up to 18 months.

The first step is to produce what is called a high immune plasma. In the case of snakes, controlled doses of venom are injected into horses because they are larger animals with a strong immune system.

Sydney Funnel - The venom of the web spider enters the rabbit without being affected by toxins. These animals have increasingly injected doses to accumulate their antibodies. In some cases, this step alone can take nearly a year.

The animal's pressurized plasma was removed from the blood, and the antibody was isolated from the plasma before bottled for administration.

CSL Seqirus produces 7,000 small vials each year, including snakes, spiders, stone fish and box jellyfish anti-venom - they are valid for 36 months. The challenge then was to make sure everyone who needed it had a supply.

"It's a huge undertaking," said Dr. Jules Bayliss, who leads the anti-venom development team at CSL Seqirus.

“First of all, we want to see them in the major rural and remote areas where these creatures may enter.”

The vial distribution depends on the species in each region. For example, the Taybans are in northern Australia and therefore do not need to resist snake venom in Tasmania.

Royal Flying Doctors also offer Antivenom, where they can access some of the most remote communities in the United States, as well as Australian navy and cargo ships for sea snake bites.

Papua New Guinea also receives about 600 small vials each year. The country used to be connected with Australia through a land bridge and shared many of the same snake species, so the Australian government offers anti-venom for free - snake diplomacy if you prefer.

"Honestly, we may have the most impact on Papua New Guinea due to snake bites and deaths," said CSL Seqirus executive Chris Larkin. So far, they believe they have saved 2,000 lives.

Back at the park, Mr Collett joked that the nickname of “Dangerous Noodles” is sometimes nicknamed to his serpentine colleagues, a trait of Australian classics that makes something reveal the nightmare of so many visitors.

However, Mr. Conlet is clear: these animals should not make people inaccessible.

He joked: "The snake is not only cruising the streets that attack the British - it doesn't work."

"If you're going to get a snake bite, that's the best place in Australia - we have the best antidotes. It's free. The treatment is not real."