The fires burning in the Los Angeles area are a powerful example of how humans have learned to fear wildfires. Fires can level entire communities in an instant. They can destroy communities, burn old-growth forests, and even suffocate distant cities with toxic fumes.

More than a century of firefighting has conditioned Americans to expect wildland firefighters to quickly extinguish fires, even as people build deeper into areas that often burn. But as the Los Angeles fires illustrate, and as journalist Nick Mott and I explain in our book This Is Wildfire: How to Protect Your Home, Yourself, and Your Community in Hot Times and our 2021 podcast The Wire As explored in , this expectation and our society’s relationship with wildfires needs to change.

Over time, widespread fire suppression, home construction in high fire risk areas, and climate change set the stage for the increasingly destructive wildfires we see today.

The legacy of firefighting

The way America handles wildfires today dates back to around 1910, when fires burned about 3 million acres in Washington state, Idaho, Montana and British Columbia. After witnessing the rapid and unstoppable spread of fires, the fledgling U.S. Forest Service developed a military-style device to extinguish wildfires.

America is really good at putting out fires. It worked so well that citizens came to accept that fighting fires was something the government did.

Today, when fires break out, state, federal and private firefighters, as well as tankers, bulldozers, helicopters and aircraft, are deployed across the country. The Forest Service claims it extinguishes 98 percent of wildfires before they burn 100 acres (40 hectares).

One consequence in places like Los Angeles is that when wildfires enter urban environments, the public wants to put them out before they cause significant damage. But the country’s wildland firefighting system wasn’t designed for this.

Wildland firefighting strategies, such as digging lines to stop fires from spreading and directing fires toward natural fuel breaks, don't work in densely populated communities like Pacific Palisades. Airborne water droplets and flame retardant droplets do not occur when high winds make flying unsafe. At the same time, the area's municipal firefighting forces and water systems were not designed for such fires — and fires that engulfed entire communities could quickly overwhelm the entire system.

Long ago, Southern California's chaparral ecosystems burned regularly, limiting fuels for future fires. But aggressive fire suppression and neglect of urban overgrowth have left many areas with excessive and easily ignited vegetation. However, it's unclear whether prescribed burning could have prevented this disaster.

This is mainly a human problem. People are building more homes and cities in fire-prone areas with little regard for wildfire resilience. This threat has been exacerbated by decades of rising global temperatures caused by greenhouse gases released from burning fossil fuels in power plants, industries and vehicles.

climate change and wildfires

The relationship between climate and wildfires is fairly simple: Warmer temperatures lead to more fires. Warmer temperatures increase water evaporation, drying out plants and soil and making them more susceptible to burning. When hot, dry winds blow, sparks in already dry areas can quickly turn into dangerous wildfires.

Given that the world is already experiencing rising global temperatures, much of the western United States is actually in a fire deficit due to measures taken to extinguish most fires. This means that, based on historical data, we expect there will be many more fires than we actually see.

Fortunately, there are things everyone can do to break this cycle.

What fire managers can do

First, everyone can accept that firefighters cannot and should not put out all low-risk wildfires.

Long-range fires that pose little threat to communities and property can energize ecosystems. Frequent natural fires also help avoid catastrophic fires caused by excessive brush buildup. They also create fuel disruptions on the ground, potentially preventing the spread of future fires.

Fire managers have advanced mapping technology that can help them decide when and where forests are safe to burn. Thoughtful prescribed burns—low-intensity fires intentionally lit by professionals—can provide many of the same benefits as the fires that historically burned in forests and grasslands.

The Forest Service aims to increase prescribed burning on more acres in more areas across the country. However, the agency has struggled to train enough staff and pay for projects, and environmental reviews have sometimes led to delays lasting years. Other groups offer beacons of hope. For example, indigenous groups across the country are fighting back.

Adapting homes to fire risks

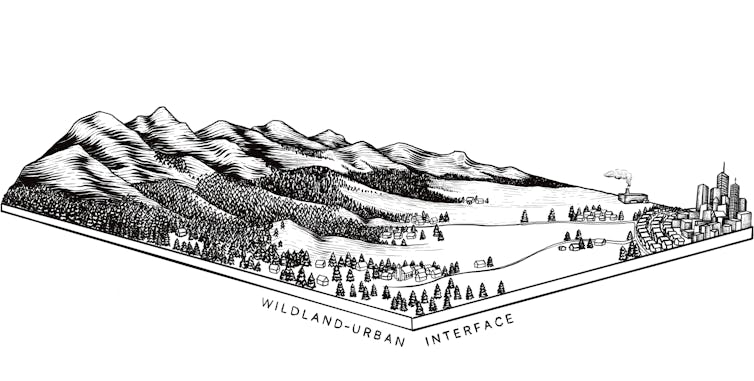

More than one-third of U.S. homes are located in the so-called wildland-urban interface, areas where homes and other buildings mix with flammable vegetation. The region now includes many urban areas that were developed without considering wildfire risk.

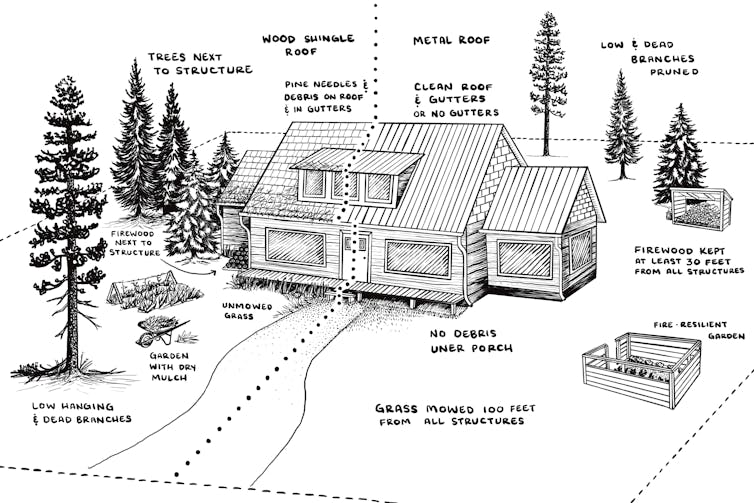

For homes, the biggest risk comes from burning embers blowing in the wind and landing in weak spots, potentially causing a house fire. These embers can be carried for miles in strong winds and settle in shrubs, trees and other flammable vegetation that clog gutters, shingle roofs or in shrubs, trees and other flammable vegetation near gutters or pine needles.

Some of these vulnerabilities are easy to fix. Cleaning your house's gutters or trimming too close vegetation requires minimal effort and tools you already have around the house.

The grant program is designed to help fortify homes to withstand wildfires. But huge investments are needed to complete the work on the scale required for fire risk. For example, nearly 1 million U.S. homes in wildfire-prone areas have highly flammable wooden roofs. Retrofitting these roofs is expected to cost $6 billion, but the investment could save lives and property and reduce future wildfire management costs.

Homeowners can refer to resources such as Firewise USA to learn about Home Fire Zones. It describes the types of vegetation and other flammable objects that pose a high risk at various distances from buildings, as well as steps to make buildings more fire-resistant.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9sel3wcBLg[/embed]

For example, there should be no flammable plants, firewood, dry leaves or needles, or anything combustible on or under decks and porches within 5 feet (1.5 meters) of your home. Grass should be cut short between 5 and 30 feet (9 meters), with tree crowns at least 10 feet (3 meters) away from buildings.

The key takeaway is that homeowners must start viewing their homes as potential fuel for wildfires.

rights to rebuild

One possible consequence of California’s devastating fires is that states and communities can develop proactive wildfire recovery policies. These include establishing zoning rules and regulations that require developers to build using fire-resistant materials and designs. Or they might ban construction in areas where the risk is too high.

California’s plan to rebuild quickly without considering wildfire safety requirements will only expose the state to more fires. The International Wildland-Urban Interface Code provides guidance for protecting homes and communities from wildfire and has been adopted by jurisdictions in at least 24 states. California is not one of them.

Living in a world full of wildfires

Prevention and suppression are always key parts of wildfire strategies. While promising new firefighting technologies are being developed, adapting to a fiery future means everyone has a role to play.

Learn how to manage wildfires in your area. Understand and address the risks to your family and community. Help your neighbors. Advocate for better wildfire planning, policies and resources.

Living in a world where more wildfires are inevitable, everyone sees themselves as part of the solution. This means we have to accept that some fires are natural and necessary, and that some of the places we love may be too dangerous to protect.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on August 22, 2023.