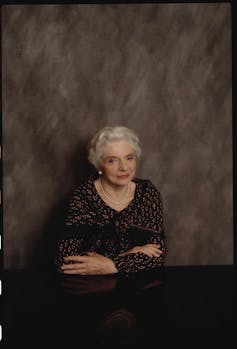

Eighty years ago, Jewish-American novelist Laura Z. Hobson was considering her next writing move and asked a friend for a little help.

The story she was drafting, "Gentleman's Agreement," felt like a bold idea. Maybe too bold. In her vision for the novel, journalist Phil Green is assigned to write an article about anti-Semitism. He pretended to be Jewish so he could experience bigotry firsthand. Readers follow this character as he encounters the prejudices of so-called good people and learns to deal with the scorn and attacks that are casually meted out to even self-identified liberal Americans.

It was 1944, three years after the United States entered World War II. However, it was Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, not the Nazis' persecution of Jews and other marginalized groups, that prompted Americans to finally fight. Throughout the early and mid-1940s, anti-Semitism remained rampant in the United States.

With so much anxiety about Jews and American soldiers risking their lives in the war, Hobson wasn't sure how a novel about domestic anti-Semitism would be received. She may have wondered whether readers would consider the story to be a "special plea" by a Jewish writer on her own behalf.

Should she continue with the novel that surges within her? To get out of her writing jam, Hobson did something she had never done before and would never do again in the four decades she had been writing a dozen books: she consulted several friends and colleagues to A novel proposal was mailed to them, along with a cover letter explaining her dilemma.

Little did she know that Hobson was about to write one of her most important books—one that would help expand the conversation about prejudice to a wider audience than heard a rabbi’s sermon or read a committee’s report on anti-Semitism. Report more.

correct words

When feedback starts coming in, it becomes clear that not all feedback is useful.

Hobson’s editor at Simon & Schuster, Lee Wright, seemed not to fully realize that writing fiction is about putting yourself in other people’s shoes. The editor advised Hobson that it was not appropriate for her to write from a Gentile perspective because Hobson herself was Jewish. Furthermore, Wright warned that Hobson should not attempt to write from a man's perspective.

Hobson's publisher and friend Richard Simon of Simon & Schuster was also skeptical. He doesn’t believe fiction is a way to combat anti-Semitism or bigotry. Then Simon did the worst thing an editor could do: He reminded Hobson that her last novel, The Invaders, had been a commercial disappointment.

Hobson was thoughtful about these responses, as evidenced by her autobiography and letters archived at Columbia University, which I discovered while researching my first book, The War Story: How Books Americanized Judaism content. As Hobson later noted in her autobiography, her publisher's less than enthusiastic reply eroded some of her confidence. She wasn't entirely sure she wanted to keep writing.

One of Hobson's closest female friends, Louise Carroll Weeden, provided just the right words of encouragement in the letter. Carol, as her friends called her, is married to television writer John Whedon, and their grandson, Joss Whedon, known for "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" and "The Avengers," is the family's writing Your career will also continue to be successful.

Carroll was familiar with the ups and downs of the writing life, as well as Hobson's insecurities, and he responded with the enthusiasm Hobson needed. “Let me say right off the bat, I think this book should be written,” Whedon assured her, “and the sooner the better—not to highlight the plight of Jews, but to examine the more dire plight of non-Jews, and the prejudices What Penetrating Poison Means for America.”

Weeden believes that the Americans who really need a "gentleman's agreement" are not extreme anti-Semites, but those who hope that "if you pretend it doesn't exist, maybe it will go away." Otherwise, she warned, willful ignorance and passivity could destroy the country — "at least the America that most people want to believe exists."

Whedon did not deny the risks. But she hated to see her friends doubt her abilities or her insights as a Jewish woman who had experienced anti-Semitism firsthand and observed casual anti-Semitism in her non-Jewish friends. Whedon was one of Hobson's non-Jewish friends, which made her enthusiasm for a novel about anti-Semitism particularly valuable to Hobson.

"This is a controversial topic, baby, and no matter what the outcome, there's going to be debate about who should do it, when and how," Whedon concluded. “To me, I think you wrote this book at a really good time — certainly in anger — but also in cold hard truth.”

Whedon brought Hobson back to his senses. Now, it's time to write.

immediate success

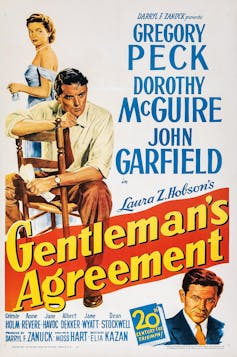

In a few years, the book that had stuck in Hobson's mind would become a sensation. Gentleman's Agreement was first published serially in Cosmopolitan magazine and subsequently printed by Simon & Schuster in 1947. It became a bestseller and later an Oscar-winning film starring Gregory Peck.

The New York Times said of this novel: "A must-read for every thoughtful citizen in this dangerous century." Because of Hobson's readable style and romantic overtones, the novel received attention from publications ranging from the Saturday Literary Review to Seventeen magazine. The Times critic Charles Poore wrote in his annual review of popular books in December 1947 that Americans learned from Hobson "how to become human beings."

Gentleman's Agreement was never viewed as "just" a Jewish novel—largely because readers mistakenly assumed that an author named Hobson was not Jewish. Even for critics, the book demonstrates a new openness to discussing anti-Semitism. This is an educational story.

Hobson's novel was part of a wave of anti-Semitic fiction in the 1940s. Some of these novels were written by Jewish writers who came to become central to postwar American literature, such as Saul Bellow and Arthur Miller. Others are by writers who became famous in the 1940s but whose names have faded into obscurity over the decades, such as Gwethalyn Graham and Jo Sinclair . But Hobson's was the most popular at the time.

However, without Whedon's encouragement, Gentleman's Agreement may never have been completed. If each of the writer's friends said the right things—offering needed encouragement or tough love—then discovering a pearl of encouragement wouldn't feel like such a profound treasure. But no one gets all the encouragement they need, and writers are no exception.