The future of the Institute of Education Science, a non-partisan research unit of the Ministry of Education, suddenly is in danger. The Trump Administration Task Force led by Elon Musk has announced plans to cancel most of the institute's contracts and training grants.

The institute has an annual budget of less than $1 billion (or less than 1% of the Department of Education budget), but it improves education by supporting rigorous research and sharing data on student progress. It also sets standards for evidence-based practice and formally lists criteria for evaluating educational research.

In short, the Institute of Educational Sciences determines what works and doesn’t work.

As cognitive scientists engaged in educational research, we believe this often overlooked institute is key to raising national standards of education and preventing pseudoscience from entering classrooms.

Dissatisfaction with American education

Getting a proper education can help address some of the biggest challenges in the United States, such as high school dropout rates and poverty.

But throughout American history, dissatisfaction with the level of student achievement has stimulated major educational reforms.

For example, the "Donor Satellite" launched by Russia launched the "National Defense Education Act" of 1958. The measure sought to strengthen scientific and mathematical guidance to strengthen defense efforts in the Cold War.

Concerns about educational inequality led to the Basic and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which funded schools that serve students from low-income families.

After President Jimmy Carter established the Ministry of Education in 1979, small government conservatives, including Ronald Reagan, promised to abolish it.

However, as president, Reagan appointed former education commissioner Terrel Bell as secretary of education. Bell convened the National Council on Excellence in Education. In 1983, it produced a country in danger, and the report warned of a “mediocre trend” in schools.

It prompts national leaders to push for higher academic standards.

In 1997, an alarm over the growing reading level of many students led to the National Reading Group, which highlighted evidence-based reading guidance.

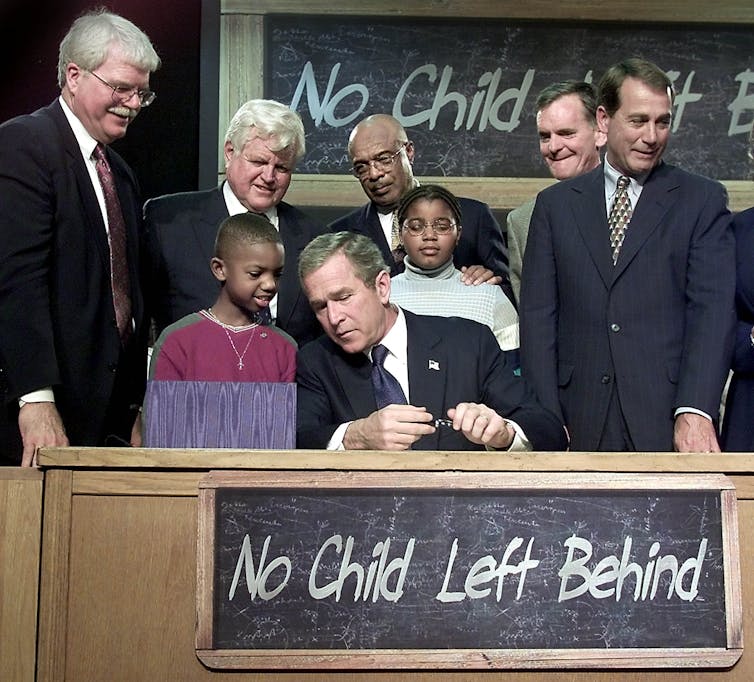

In response to the ongoing focus on American education, President George W. Bush worked with U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy to work with 2002's No Child of Chard Act Act). . It provides incentives for successful schools and penalties for failed schools.

The law greatly improves achievements, especially in mathematics.

School of Educational Sciences

Just months after Congress ratified the Lost Children Act, it established the Institute of Educational Sciences to provide independent education research, becoming the first federal agency dedicated to using scientific research to guide educational policy.

Prior to the Institute, educational research was decentralized, ideologically driven and inaccessible to parents and teachers. The findings were buried in books or locked behind a payroll wall.

The institute broke that cycle. It is led by directors and boards appointed by researchers rather than politically appointed.

It produces replicable results and allows it to be used freely to the public.

For example, the job clearinghouse launched in 2003 provides guidance for educators on effective practices. The school board seeking to pass the new curriculum can find answers on the website about effective methods.

The clearinghouse extracts the study to clear recommendations. It enables local decision makers to get involved from the need to go through complex research. The website also references the original research and provides descriptions for local decision makers who wish to examine the evidence themselves.

Since 2007, it has published 30 practical guides. They cover topics such as teaching scores, improving reading and reducing high school dropout rates.

These guidelines combine the best evidence rather than relying on a study, leader or political ideology.

However, the clearinghouse may be one of the parts of the Institute of Educational Sciences, Chopper Block.

Evidence increases freedom

From the belief in the 20th century that should be tailored to the shape of the skull of students to the 1970s movement to promote unstructured learning in classrooms without walls, pseudoscience and fashion hindered the improvement of education.

The Institute of Educational Sciences protects educational freedom by opposing these claims.

Some believe that the free market should determine educational options. They believe that parents and school boards will naturally tend toward effective plans, while invalid plans disappear.

However, the education market usually has the best marketing rewards program, not the best results. Psychologists who study scientific thinking have documented how pseudoscience programs gain appeal through fascinating narratives rather than evidence.

Meanwhile, public trust in expertise is declining, and pseudoscience products are flooding the market. Programs such as brain balance and learning RX are booming in the $2 billion brain training industry.

These products are sold directly to parents of children with learning difficulties, using smooth advertising and claiming to “reconnect” the child’s brain to enhance learning. Families pay thousands of dollars for evidence of a lack of reliable, peer-reviewed enduring interest.

Programs designed by university scholars also cannot have an impact on the temptation of anecdotes on hard data.

Former Columbia professor Lucy Calkins downplayed the importance of teaching phonology, thus undermining the reading development of a generation of students. The controversial idea of Stanford University professor Jo Boaler delayed Algebra I in some California schools until the ninth grade and blocked the practice of timed arithmetic.

Despite a lot of evidence that it doesn’t work, education against drug abuse has flourished for decades.

These examples reveal good but ineffective educational products obtained through public attraction rather than rigorous research.

The future of IES

In 2007, the Office of Management and Budget awarded the Institute of Educational Sciences’ program assessment rating tool, a distinction of only 18% of the federal program.

But most Americans may never have heard of it.

This highlights the Institute’s main weakness: it is not enough to share its discovery and practical guides with public and decision makers.

The institute will promote its findings more widely so that parents and education leaders can better access rigorous research to improve education.

Regardless of the change made to the education sector, the role of the Institute in providing the most effective research and ensuring continuous communication between research and practice will benefit the American public.