Imagine a Florida black panther on the way to the large cypress swamp in the southwest of the state (645 kilometers) and reach the Okefenokee Swamp in the southwest of the state, on the Okefenokee Swamp on the border between Florida and Georgia without being discovered by humans.

No one has recorded the trip of the leopard. But there is evidence that this happened.

Florida Black Panthers used to be distributed throughout much of the Southeastern United States, but now their populations are small - maybe around 200 - their known breeding range is greatly reduced and is now concentrated in southwestern Florida.

When young men travel north to escape social pressure from adult men, they do appear in North Florida and Georgia. Biologists discovered their tracks not far south of Okefenokee. A black panther was almost Atlanta before being shot by a hunter.

Large mammals such as Florida leopards and black bears actually need space to roam to hunt, reproduce, and thrive. Thanks to the Florida Wildlife Corridor, a statewide system of connected wildlife habitats, 15 years old.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor builds on conservation efforts in the 1980s and 1990s, when researchers at the University of Florida, including the two of us and our mentor, Larry Harris, created a map of existing and proposed conservation areas that are interconnected with the state.

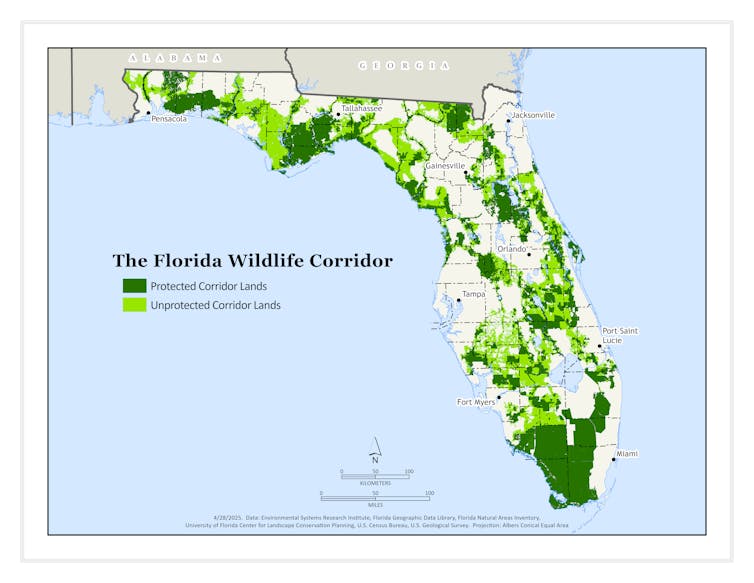

Today, the Florida Wildlife Corridor covers 18 million acres, about half of the state.

One hundred acres of one hundred are protected. They are local, state, regional or federal publicly protected land, or privately protected easements. These easements limit landowners' activities compatible with wildlife conservation, such as pasture, wood production and other sustainable activities.

The other 8 million acres are the focus of state-funded land conservation efforts to close unprotected gaps. Currently, these lands can be transformed into intensive residential, commercial or industrial development.

The corridor is an ambitious conservation project. It provides enough habitat to maintain healthy wildlife populations while also protecting Florida's major ecosystem services, including water quality and flooding. Ecosystem services refer to the benefits provided by ecosystems to mankind.

Corridors are also a unique example of how conservationists can combine science with public education and outreach to protect important natural habitats, even in areas like Florida, facing thriving population growth.

Florida's population is booming

Until the early 20th century, Florida was the most remote and least developed state on the East Coast.

After World War II, Florida introduced affordable home air conditioning, transforming from a sleepy winter vacation destination to the third largest state in the United States.

Currently, about 300,000 new residents move to Florida each year.

With the growth of population, natural habitat and rural landscapes are rapidly lost. Using federal land use data, we calculated approximately 60,000 acres of Florida habitat each year.

Florida's development was initially concentrated on the coast, especially in areas with wide beaches. With the opening of tourist attractions such as Disney World near Orlando in 1971, central Florida also became a hub of rapid growth.

It is obvious to the Floridians who care that almost all lands protected without the permanent protection name may eventually lose the spread of cities and suburban areas.

To address these concerns, Florida has become a leader in land conservation, which is often popular and in a sunny state.

Since the 1970s, Florida has protected millions of acres of protected land by including the Florida Preservation 2000 Act of 1990, which replaced the Florida Conservation Plan in 2001, and the rural and family land conservation plan established in 2001.

Scientists identify key areas of protection

Since the 1930s, wildlife biologists have observed how birds and mammals use trees, hedges, streams and other natural corridors to travel through agricultural areas in the United States and Canada.

When corridors are protected, they allow animals to travel safely in the landscape and can save animals from extinction. They also provide ecosystem services to people, such as clean water and flood control.

Since 1995, the Florida Ecological Greenway Network (FEGN) has identified a statewide system that is complete with natural areas and connects green spaces. Now, it is part of the National United Florida Greenway and Trail System, a statewide network of recreational trails and ecological corridors.

As conservation scientists who have been deeply involved with FEGN, we were able to leverage the state’s early investment in geographic information systems. GIS produces digital maps and other high-quality data in wildlife habitats and other conservation priorities.

We continue to work with state agencies and other partners to continuously update FEGN as land use changes change and better data and tools are available to identify areas of conservation priorities.

Get the public to join

Although FEGN proves to be the basic basis for supporting the national protection program, it is not widely known to Floridians or visitors to the state.

In 2010, conservation photographer Carlton Ward and colleagues proposed a simple, unified map and a public campaign to promote the conservation of top land in Florida’s ecological greenway network.

Ward calls it the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

He organized a team of photographers, videographers and scientists who hike through large corridors to document Florida's natural ecosystems and native species threatened by development.

These expeditions highlight species such as Florida black bear, Florida black bear and Florida grasshopper. They raise awareness of corridors’ connections with water conservation, land managed by ranchers and foresters, and recreational opportunities. They have produced documentaries, media and social media coverage, as well as public negotiations and events to educate the public about the importance of the corridor of conservation.

Support from both parties continues

In June 2021, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act into law. The legislation has been unanimously supported by the state legislature, formally acknowledging the corridor’s critical role in Florida’s economic, cultural and natural heritage and in the conservation of dangerous species and ecosystems.

The law also reinvigorates legislative support and funding to directly acquire land for protection and establish protection easements on private land.

2025-2026 The Florida budget, which is still under negotiation, designates $300 million to $450 million for the land conservation program.

On April 23, 2025, the Florida Senate passed a resolution declaring April 22 as Florida Wildlife Corridor Day. The resolution confirmed the importance of the corridor as a “unique natural resource” which is crucial to “preserving green infrastructure is the foundation of the state’s economy and quality of life.” ”

There is still a lot of land conservation efforts to be done in the competition with emerging populations. But Florida has proven ready to implement a science-based strategy and work with willing landowners to protect statewide wildlife corridors, a key element of Florida's future.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor is also a potential model for other states and regions that want to protect feasible wildlife populations and ecosystem services.