Network correspondent

Almost every day, my phone calls carry messages from hackers from all the stripes.

Good, bad, not that hard.

I've been covering cybersecurity for over a decade, so I know many of them love to talk about their hacks, discoveries and escapes.

About 99% of these conversations are firmly locked in my chat logs and will not lead to news coverage. But recent pings cannot be ignored.

"Hey. This is Joe Tidy of the BBC's coverage of this collaboration news, right?" The hacker called me in the telegram.

They laughed and said, "We have some news for you."

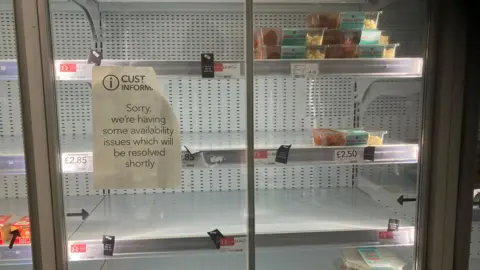

When I asked cautiously what this was, the person behind the telegram account (without a name or profile picture) gave me an internal track on what they claimed to have done to M&S and the co-op, which was in a cyber attack that caused massive disruptions.

Through the back and forth message over the next five hours, it was clear that these obvious hackers were fluent in speaking and despite their claim to be messengers, it was clear that they were closely related to M&S and CO-S and CO-COP Hacks - if not closely related.

They share evidence that they have stolen a large amount of private customer and employee information.

I checked the example of the data they gave me - and then deleted it firmly.

Confirm suspicious news

They are obviously frustrated that the co-ops are not succumbing to their ransom demands, but will not say how much they ask retailers for their Bitcoins in exchange for their promise that they will not sell or disclose stolen data.

After talking to the BBC's editorial policy team, we believe that the public interest is reported to have provided us with evidence that they are responsible for the hacking.

I quickly contacted the co-op’s news team for comment and, within minutes, initially downplayed the hack, acknowledging a massive data breach to employees, customers and the stock market.

Shortly after, the hacker sent me a long-term angry and offensive letter about the co-op’s reaction to their hacking and subsequent ransomware, suggesting that retailers nearly dodged the more serious hack by stepping into the messy few minutes after their computer systems were infiltrated. Letters and conversations with hackers confirm what experts in the cybersecurity community have been saying since retailers began attacking retailers — the hackers come from a cybercrime service called Dragonforce.

Whose Dragonforce you might ask? Based on our conversations with hackers and extensive knowledge, we have some clues.

Dragonforce provides various services to cybercriminals on its Darknet website in exchange for 20% of all ransoms collected. Anyone can register and use their malware to compete for victims’ data, or use their DarkNet website for public ransomware.

This has become the norm for organized cybercrime; it is called ransomware as a service.

Recently, the most notorious thing is a service called Lockbit, but that's almost entirely due to being cracked by police last year.

After the removal of such groups, an electric vacuum appeared. Tips for dominance in this underground world, leading some competitors to innovate their products.

The power struggle that follows

Dragonforce recently reinvented itself as a cartel, offering more options for hackers including 24/7 customer support.

Network experts such as Hannah Baumgaertner, head of research at cyber risk protection company Silobeaker, said the group has been advertising a wider range of products and has been actively targeting organizations since 2023.

"Dragonforce's latest model includes features such as management and client panels, encryption and ransomware negotiation tools," Ms Baumgaertner said.

As a stark example of the dynamic struggle, Dragonforce’s Darknet website was recently hacked and tainted by a rival gang called Ransomhub, and then reappeared about a week ago.

"There seems to be some brawl behind the scenes of the ransomware ecosystem - this may be for the 'main' leader' position, or just to undermine other groups to take up a share of the victims," said senior threat researchers at cybersecurity firm SecureWorks.

Who is playing the strings?

Dragonforce's prolific tactics will release information about the victims as it has completed 168 times since December 2024 - a London accounting firm, an Illinois steel manufacturer, and an Egyptian investment company are all included. However, Dragonforce has remained silent on retail attacks so far.

Typically, radio silence about the attack shows that victim organizations have paid hackers to keep quiet. Since Dragonforce, Co-Op, and M&S have not commented on this point, we don't know what will happen behind the scenes.

It is tricky to determine the people behind Dragonforce, and it is unclear where they are. When I asked their telegram account, I didn't get the answer. Although the hackers didn't explicitly tell me that they were behind recent hacks on M&S and Harrods, they confirmed that a Bloomberg report was spelled out.

Of course, they are criminals and may be lying.

Some researchers say Dragonforce is located in Malaysia, while others say Russia, many of which are believed to be located in it. We do know that Dragonforce has no specific goals or agenda besides making money.

And if Dragonforce is just a service used by other criminals - who is playing the strings and choosing to attack British retailers?

In the early stages of the M&S hack, unknown sources told the web news website that the leaked computer showed evidence that a group of cyber criminals known as scattered spiders — but this has not been confirmed by police.

In a normal sense, scattered spiders are not really a group. It's more of a community that spans dissonance, telegraph and forums and other sites - so CrowdStrike's cybersecurity researchers gave their description "dispersed".

They are known to speak English, probably among the UK, the US and young people - in some cases teenagers. We know this from researchers and previous arrests. In November, the United States accused five men and boys in their twenties of charges over alleged dispersed spider activity. One of them is Tyler Buchanan, a 22-year-old Scotsman who did not plead guilty, and the rest is us.

However, the police crackdown appears to have little effect on the hacker's determination. On Thursday, Google's cybersecurity department issued a warning that spider-like attacks on U.S. retailers are now also starting.

As for the hackers I talked to on the telegram, they refused to answer whether they were scattered spiders. They said "we won't answer this question".

Perhaps in a nod to the immaturity and attention-seeking nature of hackers, two of them said they wanted to be called "Raymond Reddington" and "Dembe Zuma," a character involved in the American crime thriller Blacklist, which involved a wanted criminal who helped a policeman seize other criminals on the blacklist.

In the message I gave me, they boasted: “We are blacklisting UK retailers.”