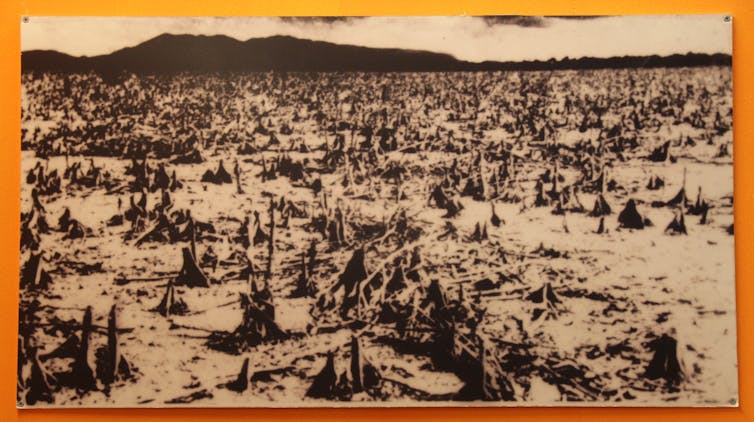

When the Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, it left behind a landscape that caused environmental damage. The coastal mangrove fragments that once had abundant fish and birds lie in the ruins. The forest with hundreds of species is reduced to dry debris, covered with invasive grasses.

The term “ecocide” was coined in the late 1960s to describe the use of herbicides such as agents orange and Napalm to fight guerrillas using jungle and swamps for cover.

Fifty years later, Vietnam’s degraded ecosystems and dioxin-contaminated soils and waters still reflect the long-term ecological consequences of the war. Efforts to restore these damaged landscapes, and even assess long-term hazards, are limited.

As an environmental scientist and anthropologist who has worked in Vietnam since the 1990s, I found neglect and slow recovery work annoying. Although war stimulated new international treaties aimed at protecting the environment in wartime, these efforts failed to force the post-war recovery of Vietnam. The current conflict between Ukraine and the Middle East shows that these laws and treaties are still inefficient.

Agent Orange and Daisy Cutter

The United States first sent ground troops to Vietnam in March 1965 to support South Vietnam's anti-revolutionary forces and North Vietnamese forces, but the war has been going on for many years. To fight an elusive enemy at night, the U.S. military turned to environmentally modified technology from the hiding place deep in the swamps and jungle.

The most famous of these is the Ranch Hand Operation, which sprays at least 19 million gallons (75 million liters) of herbicides on approximately 6.4 million acres (2.6 million hectares) in southern Vietnam. The chemicals fell on forests, and also on rivers, rice fields and villages, exposing civilians and troops. More than half of the spray involves dioxin-contaminated defoliator orange.

Herbicides are used to peel off leaf coverings from the forest, increase visibility along the route, and destroy crops suspected of supplying guerrillas.

As news of the damage caused by these strategies recovered the United States, scientists raised concerns about the campaign’s environmental impact on President Lyndon Johnson, calling for a review of whether the U.S. intentionally uses chemical weapons. The U.S. military leader’s position is that herbicides do not constitute chemical weapons in the Geneva agreement and the U.S. has not yet approved it.

During the war, the scientific organization also launched research within Vietnam, discovering widespread damage to mangroves, economic losses to rubber and timber plantations, and damage to lakes and waterways.

In 1969, there was evidence to link the orange chemical (2,4,5-T) to birth defects and stillbirth in mice because it contains TCDD, a particularly harmful dioxin. This led to a ban on the use of domestic uses by the military in April 1970 and the last mission was carried out in early 1971.

Burning weapons and forest cleaning also destroyed Vietnam's rich ecosystems.

The U.S. Forest Service tested the massive incineration of the jungle by fuel barrels dropped from the plane. Civilians were particularly concerned about the use of napalm bombs, and more than 400,000 tons of thickened oil were used during the war. After these hells, invasive grass often takes over in hard sterile soil.

"Roman Plow", a large bulldozer with armored cutters can remove 1,000 acres per day. The giant concussion bomb, known as the "daisy cutter", flattened the forest and triggered a shock wave, killing everything within a 3,000-foot (900-meter) radius, dropping to earth in the soil.

The United States also made weather modifications through the Popeye project, a secret program from 1967 to 1972, which sowed clouds with silver iodide to extend the monsoon season, trying to reduce the flow of fighter jets and supplies from the Ho Chi Minh trail in North Vietnam. Congress finally passed a bipartisan resolution in 1973 urging international treaties to prohibit the use of weather modifications as weapons of war. The treaty came into force in 1978.

The U.S. military argues that all these strategies have been successful in the trade in life in the United States.

Despite Congressional concerns, there is little review of the environmental impact of U.S. military operations and technology. Research sites are difficult to access and do not have regular environmental monitoring.

Recovery is slow

After Saigon's downfall of Taipei Vietnamese forces on April 30, 1975, the United States imposed a trade and economic embargo on Vietnam as a whole, leaving the country both hurt by war and a cash gap.

Vietnamese scientists told me they pieced together small-scale research. Bird and mammal diversity has been found to decline dramatically. In the ALướI valley in central Vietnam, 80% of the forests were not restored in the early 1980s. In these areas, biologists have found only 24 bird species and 5 mammals, far lower than normal species in undeveloped forests.

Only a few ecosystem restoration projects have been tried and are hampered by budgets. Most notably, it began in 1978 when Foresters began to manually cancel mangroves at the Saigon estuary of the Cần Giờ Forest, and the area has been completely stripped.

Inland, extensive tree planting programs in the 1980s and late 1990s finally took root, but they focused on planting exotic trees, such as Acacia, which did not restore the original diversity of natural forests.

Chemical cleaning is still there

Over the years, despite recognition of dioxin-related diseases among U.S. veterans, the United States has also denied responsibility for Agent Orange, suggesting that tens of thousands of Vietnamese may continue to be exposed to dioxins.

The first restoration agreement between the two countries only took place in 2006 after continued advocacy by veterans, scientists and NGOs, resulting in $3 million in Congress for restoring the DA Nang airport.

The project, completed in 2018, treated 150,000 cubic meters of soil at a final cost of more than $115 million, mainly paid by the U.S. International Development Agency or the U.S. Agency for International Development. Cleaning requires draining and contaminated soil to be carried out 9 feet (3 meters) deeper than expected to build up and heat to break down dioxin molecules.

Another major hot spot is the contaminated Biên Hoà Airbase, where local residents continue to absorb high levels of dioxin through fish, chicken and duck.

The orange barrel is stored at the bottom, leaking a lot of toxin into the soil and water, and it continues to accumulate in the animal tissue as the animal tissue moves upwards the food chain. The repair began in 2019; however, further work is at risk as the Trump administration almost eliminates the US Agency for International Development, and it is not clear whether any U.S. experts in Vietnam are responsible for managing the complex project.

The laws to prevent future “ecological agents” are complex

Although the health effects of Agent Orange have been under scrutiny, its long-term ecological consequences have not been well studied.

Today's scientists have chosen far more than 50 years ago, including satellite images, which are used in Ukraine to identify fires, floods and pollution. However, these tools cannot replace ground surveillance that is often restricted or dangerous during wartime.

The legal situation is equally complex.

In 1977, Geneva practices for conduct during the war were revised to prohibit "wide, long-term and serious damage to the natural environment". The 1980 agreement restricted the burning of weapons. However, the oil fires caused by Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War and the latest environmental damage in the Gaza Strip, Ukraine and Syria show that there is no strong mechanism to ensure compliance, rely on the restrictions of the treaty.

The ongoing international campaign calls for amendments to the ICC's Roman regulations to make Ecocide the fifth prosecution of crimes, as well as genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and aggressiveness.

Some countries have adopted their own ecological attack methods. Vietnam was the first person to be legally stipulated in its criminal law: “Whether in peace or war, whether in peace or war, it constitutes a crime against humanity.” However, despite several cases of pollution, the law did not lead to no prosecution.

Both Russia and Ukraine have ecological laws, but these laws do not prevent harm or be liable for damage during ongoing conflict.

Lessons for the future

The Vietnam War reminds people that failure to resolve ecological consequences after war and after will have long-term effects. The remaining supply is a political will to ensure that these effects are neither overlooked nor repeated.