Iran returns to pragmatism – The Atlantic

timeiranian president seems Becoming a cursed position. Of the eight people who have served before the current president, five ultimately found themselves politically marginalized after their terms ended. Two others fell to their deaths in offices (bomb attack in 1981, helicopter crash in 2024). The only exception was Ali Khamenei, who later became the Supreme Leader.

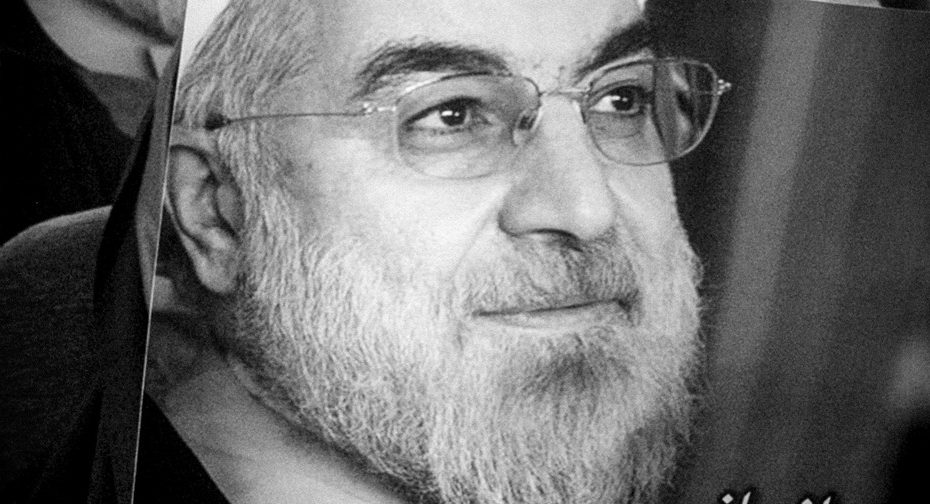

Hassan Rouhani, Iran's centrist president from 2013 to 2021, may be poised to break the curse and stage a political comeback.

Until recently, this prospect seemed far-fetched. Under pressure from hard-liners on the one hand and the Islamic Republic's opposition on the other, the regime's centrists and reformists have become political irrelevances. During the last years of Rouhani's rule, he was one of the most hated men in Iran. His landmark achievement, the 2015 nuclear deal with the Obama administration and five other powers, was destroyed when President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal in 2018. Iranian security forces outside the president's control killed hundreds of protesters in 2017 and in 2019, he looked on. He was succeeded by hardline Ebrahim Raisi in 2021 in an uncontested election. Hardliners, backed by Khamenei, continue to seize most of the available instruments of power in Tehran. Last January, Rouhani was even denied a bid for the seat he has held since 2000 in the Assembly of Experts, the body responsible for appointing the top leader.

But events in 2024 changed the balance of power in the Middle East and within Iran. Israel’s strikes against Hamas and Hezbollah have significantly weakened Iran’s so-called axis of resistance. The collapse of Assad's regime in Syria last month was the final nail in the Axis' coffin. Khamenei’s foreign policy is now in ruins. Last year, Iran and Israel conducted missile and drone attacks on each other's territory for the first time in history. After Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash in May, Khamenei allowed reformist Masoud Pezeshkian to run for and win the presidency — a significant concession since reformists had been effectively excluded for nearly two decades. Outside of national politics, it is even banned. Now, Rouhani's star foreign minister Javad Zarif is back as Pezeshkian's vice president for strategic affairs. Both Rouhani and Zarif campaigned for Pezeshkian and found themselves on the winning team.

Hard-liners have brought international isolation, domestic repression and economic ruin to the country, and they find themselves red-faced. Although Khamenei, who is nearly 86 years old, is still in full power, he has lost a lot of respect, not only among the people, but also among the elite, and the battle for his successor has begun. Recently, Khamenei indicated that he might be willing to abide by anti-money laundering conditions set by the Paris Financial Action Task Force. If Iran hopes to solve its economic problems, it has no choice: the country is currently one of only three countries on the FATF blacklist (the other two are North Korea and Myanmar). But the issue has long been a sensitive one for hardliners, who view cooperation with the FATF as a capitulation to the West and worry it will force Iran to reduce its support for terrorist groups.

A bold Rouhani returned to the spotlight, delivering speeches and defending his tenure. Over the past few months, he has repeatedly complained that his administration could have directly engaged with Trump but was prevented from doing so. (This was a hint to Khamenei, who in 2019 publicly rejected then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s message to Tehran from Trump.) Rouhani’s call for “constructive interaction with the world” was The endorsement of the regime. Negotiate with the United States to lift sanctions. He recently said that none of Iran's problems can be solved without addressing sanctions. He also called for “listening to the will of the majority” and freer elections. The comments have made him a renewed target for hard-liners such as Saeed Jalili, who lost to Pezeshkian in elections last year.

In this context, what appears to be a factional squabble is significant. Rouhani represents a segment of the Iranian establishment that rejects Khamenei's threats of force against the United States and Israel on pragmatic grounds. In many ways, he is the political successor of Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. Rafsanjani was a once powerful former president who eventually clashed with Khamenei and died in 2017. Rafsanjani and Rouhani are often compared to the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping. They seek to transform Iran from an ideologically anti-Western country into a technocratic state with a pragmatic and even Western-oriented foreign policy. Rouhani has made state visits to France and Italy during his term as president and has been accused of neglecting Iran's ties with China and Venezuela. His cabinet includes many U.S.-educated technocrats, and his administration has tried to buy American-made Boeing planes.

Iran's centrists are less interested in democratization than the reformists, who are more focused on promoting economic development and good governance. This emphasis allows them to expand their scope. Rouhani’s pragmatic developmentalist agenda is shared not only by reformists but also by many powerful conservatives, including the Larijani brothers, a wealthy clerical family that includes several former senior officials; Former Speaker Ali Akbar Natq Nouri, former Interior Minister Mostafa Pourmohammadi, and even current Speaker of Parliament Mohammad-Bagher Qalibaf Bagher Qalibaf) (Supreme Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps for many years).

Iran's current weakness and desperation provide Rouhani and his allies with an opportunity to regain power. Doing so would put them in a good position for the inevitable moment when Khamenei dies and the next supreme leader must be elected. Rouhani has qualities that make him ideally suited to play a role in this internal power struggle. Unlike soft-spoken reformist clerics such as former President Mohammad Khatami, he is a wily man who spent decades in top security posts before becoming president. (Khatami served as Iran’s chief librarian and culture minister; Rouhani served as national security adviser.) During his two terms as president, Rouhani was unafraid to stand up to rival power centers such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. His experience negotiating with the West dates back to before the Obama era. He led Iran's first nuclear negotiating team in the early 2000s, earning the nickname “The Diplomatic Sheik.” In the mid-1980s, a negotiating team led by Rouhani met with Robert McFarland, President Ronald Reagan's national security adviser, and reached an arms-for-hostages agreement known in the United States as the “Iran-Contra.” In 1986, Rouhani even met with top Israeli security official Amiram Nir (posing as an American) to request help against Iranian hardliners.

But does Rouhani have any reasonable chance of returning to power? As always, Tehran is awash with discord. A former conservative official who spoke to me on the phone from Tehran said Rouhani was the leading candidate to succeed Khamenei as supreme leader. The official spoke on condition of anonymity because “we have been ordered not to discuss succession.” A senior cleric and a former reformist lawmaker cited the same gag order but observed Rouhani's fortunes rising; they declined to predict whether he would become supreme leader.

Reformist cleric Mohammad Taqi Fazel Meybodi is less optimistic. “I don’t believe that someone like Rouhani can do much,” he told me by phone from his home in Qom. “They have no power and hard-liners are against them. These hard-liners continue to oppose the United States and have an ideological worldview. They control parliament and many other institutions.”

Fatemeh Haghighatjoo, a former reformist lawmaker turned activist in Boston, believes the regime will seek a deal with the United States no matter who is in power. “The regime has long had two views,” she told me: “One is developmentalist, and the other wants to export the Islamic revolution. But the latter’s plan is still failing. Iran has no choice but to return to development. ” Even in what many believe is the worst-case scenario – if Mojtaba Khamenei, the leader's son known for his ties to the security establishment, succeeds his father, he will be forced to adopt a developmentalist line.

Hajigatjo even hopes that the new Trump administration, which is willing to break with past norms, will provide opportunities for normalization between Iran and the United States, an approach that will “give strength to developmentalists, especially when the Axis powers are weakened”. she said.

Khamenei continues to resist this notion. In a provocative speech on January 8, he lambasted the United States as an imperialist power and pledged that Iran would continue to “support resistance movements in Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon and Yemen.” He criticized “those who want us to negotiate with the United States… and open an embassy in Iran.”

But Iran is in dire straits, and the Supreme Leader can only ignore the facts for so long. In many ways, he resembles his predecessor, revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini, who in 1988 compared his acceptance of a ceasefire with Iraq to “drinking a cup of poison.” For years, Khomeini had promised that Iran would keep fighting until Saddam Hussein was overthrown, but at the urging of Rafsanjani and Rouhani, Khomeini reversed course in desperation (young Zari Husband, then a diplomat at Iran's mission to the United Nations, helped write Iran's letter to the UN Security Council formally accepting the ceasefire).

Many analysts now wonder aloud whether Khamenei will drink his poisoned wine, too. He may have no choice. The old ayatollah's plans have apparently stalled – and Iran's pragmatists have new impetus.