Chilean woman suffering from muscular malnutrition becomes face of euthanasia debate at the main Bill stall

Santiago, Chile – As a kid, Susana Moreira's energy didn't have the same energy as her siblings. As time passed, her legs stopped walking and she lost the ability to bathe and take care of herself. Over the past two decades, the 41-year-old Chilean has been bedridden and suffers from degenerative muscle dystrophy. When she eventually loses the ability to speak or fails in her lungs, she hopes to be able to choose euthanasia – currently banned in Chile.

Moreira has become the public face of Chile's decade-long debate on euthanasia and assisting with dying debates, a bill promised by Gabriel Boric's left-wing government when he came to power last year, a critical period of approval before the November presidential election.

“This disease will progress and I will reach a point where I can't communicate,” Moreira told the Associated Press that she lives with her husband in the House of Representatives in Santh Santiago. “The time is up, and I need the euthanasia bill to become a law.”

In April 2021, Chile's representatives approved a bill to allow euthanasia and commit suicide for people over 18 who suffer from end or “severe and incurable diseases.” But it has since been stagnant in the Senate.

The initiative seeks to regulate euthanasia, where doctors can cause death and assist suicide, where doctors provide the deadly substances that patients commit suicide.

If the bill passes, Chile will join a group of countries that allow euthanasia and assisted suicide, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, Canada, Spain and Australia.

This will also make Chile the third Latin American country to establish Colombia and Ecuador’s recent decriminalization, which still remains unfulfilled due to the lack of regulations.

When she was 8, Moreira was diagnosed with shoulder muscle dystrophy, a progressive genetic disease that affects all her muscles and causes dyspnea, swallowing and extreme weaknesses.

Confined to bed, she spent a lot of time playing video games, reading and watching Harry Potter movies. Outings are rare and require preparation, as intense pain only allows her to sit in a wheelchair for three or four hours. As the disease progresses, she said she feels “urgent” to speak out to promote discussions in Congress.

“I don't want to live to a machine, I don't want tracheostomy, I don't want feeding tubes, I don't want to let the ventilator breathe. As long as my body allows me, I just want to live.”

Last year, Moreira revealed her condition in a letter to President Policing last year, detailing her daily struggles and demanding that he authorize euthanasia.

Boric released Moreira's letter to Congress in June and announced that the passage of the euthanasia bill would be a priority for his last year in office. “Through this law is an act of sympathy, responsibility and respect,” he said.

But hope will soon give way to uncertainty.

Almost a year after the announcement, multiple political unrest demoted Boric's commitment to social agenda to the background.

Chile, a country with about 19 million residents in the southern end of the southern hemisphere, began debate on euthanasia a decade ago. Despite the strong influence of the population and churches that were mainly Catholic at the time, Vlado Mirosevic, a representative from the Chilean Liberal Party, first proposed the euthanasia bill and assisted death in 2014.

The proposal is full of doubt and strong resistance. The bill has experienced a lot over the years and has made little significant progress until 2021. “Chile was one of the most conservative countries in Latin America at the time,” Mirosevic told the Associated Press.

However, recently, Chilean public opinion has changed, showing a greater problem of open debate. “The mood has changed, and today, we have a scenario of absolutely significant support for the euthanasia bill (population).”

Indeed, recent investigations have shown strong public support for euthanasia and assisted in death in Chile.

According to a 2024 survey by Chile’s Public Opinion Poll, 75% of the people interviewed said they support euthanasia, while a study by the Public Research Centre found that an October study found that 89% of Chileans believed that it should be “permitted” or “permitted under special circumstances”, and that the program should not be allowed compared to 11% compared to 11%. ”

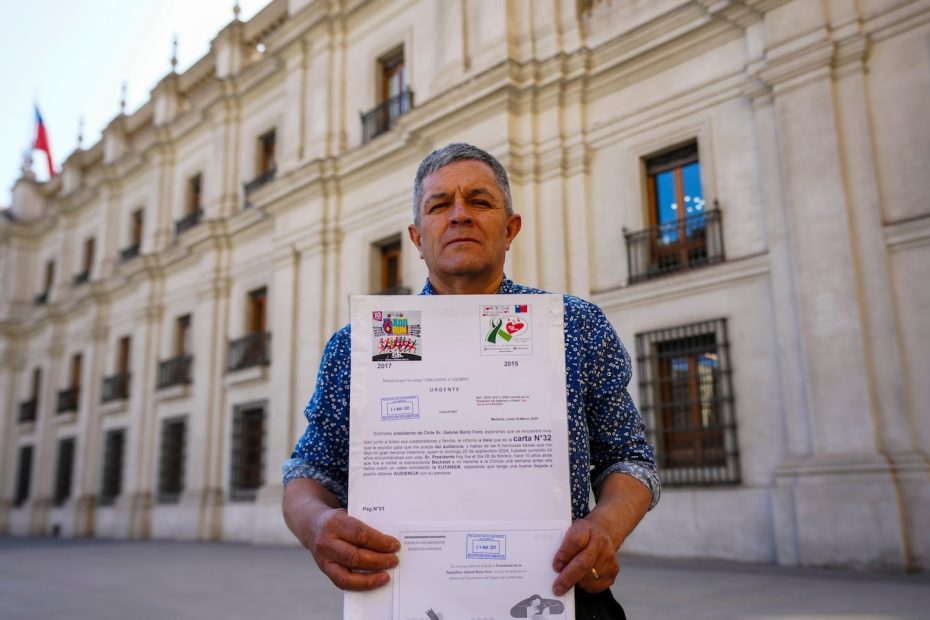

Boric's commitment to the euthanasia bill has been welcomed by terminally ill patients and families, including Fredy Maureira, a decade-long advocate demanding a choice when to die.

His 14-year-old daughter Valentina released a video in 2015 that attracted the euthanasia of then-Michelle Bachelet. Her request was denied and she died less than two months later due to complications of cystic fibrosis.

Her story created a commotion inside and outside Chile, allowing debates about assisted death to penetrate the social sphere.

“I have spoken to Congress many times, asking lawmakers to place themselves in the shoes of a child or sibling who begs for death, and there is no law that can allow it,” Morera said.

Despite growing public support, euthanasia and assisted death remain a controversial issue in Chile, including health professionals.

“It is only time to sit down and discuss euthanasia when all palliative care ranges are available and accessible,” said Irene Muñoz Pino, a nurse, academic and consultant at the Chilean Society of Nursing. She refers to the recent law enacted in 2022 that ensures palliative care and protects the rights of terminally ill individuals.

Others argue that the lack of assisted dying legal medical options may lead patients to seek other risky, unsupervised alternatives.

“Unfortunately, I've been hearing about what could be medically assisted death or euthanasia,” said Monica Giraldo, a Colombian psychologist.

With just a few months left, Chile's left-wing government faces a narrow window to dominate the political agenda by passing an euthanasia bill ahead of the November presidential election.

“A sick person is not sure of anything; the only certainty they have is that they suffer,” Morera said. “Knowing that I have a chance to choose is to reassure me.”

___

Follow AP coverage in Latin America and the Caribbean