AI trained to spot warning signs in blood tests

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis is the third in a six-part series exploring how artificial intelligence is transforming medical research and treatment.

Ovarian cancer is “rare, underfunded and deadly”, said Audra Moran, director of the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance (Ocra), a global charity based in New York.

As with all cancers, the earlier it is detected, the better.

Most ovarian cancer starts in the fallopian tubes, so by the time it reaches the ovaries, it may have spread elsewhere as well.

“You may have to detect ovarian cancer five years before symptoms appear to have an impact on mortality,” Ms Moran said.

But new blood tests are emerging that harness the power of artificial intelligence (AI) to spot early signs of cancer.

Not just cancer, AI can speed up other blood tests for potentially fatal infections like pneumonia.

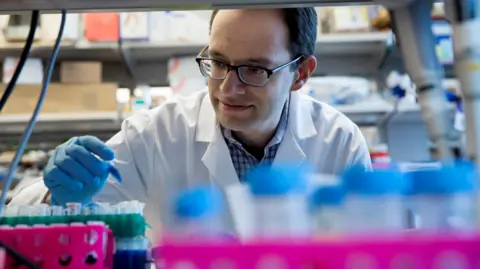

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer CenterDr. Daniel Heller is a biomedical engineer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

His team developed a testing technique that uses nanotubes, tiny carbon tubes about 50,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

About 20 years ago, scientists began discovering nanotubes that could emit fluorescence.

Over the past decade, researchers have learned how to change the properties of these nanotubes so that they respond to nearly anything in the blood.

It is now possible to place millions of nanotubes into a blood sample and make them emit light at different wavelengths depending on what material is attached to them.

But that still leaves the problem of interpreting the signal, which Dr. Heller likened to looking for a match in a fingerprint.

In this case, fingerprints are patterns of molecules that bind to the sensor, with varying sensitivities and binding strengths.

But the patterns are too subtle for humans to discern.

“We can look at the data, but we simply can't understand it,” he said. “We only see different patterns with artificial intelligence.”

Decoding the nanotube data means loading the data into a machine learning algorithm and telling the algorithm which samples came from people with ovarian cancer and which samples came from people without ovarian cancer.

These include blood from people with other forms of cancer or other gynecological conditions that may be confused with ovarian cancer.

One challenge in using artificial intelligence to develop a blood test for ovarian cancer research is that there is relatively little of it, which limits the data on which to train the algorithm.

Even though most of the data is stored at the hospital where treatment is given, there is little data sharing among researchers.

Dr. Heller described training the algorithm using available data from just 100 patients as a “Hail Mary pass.”

But he says AI can achieve better accuracy than today's best cancer biomarkers — and this is just a first attempt.

The system is undergoing further research to see if it can be improved using a larger sensor set and samples from more patients. More data can improve algorithms, just as self-driving car algorithms can be improved with more street testing.

Dr. Heller has high hopes for this technology.

“What we want to do is classify all gynecological conditions – so when someone comes in with a complaint, can we give doctors a tool to quickly tell them whether it's more likely to be cancer, or this cancer than That kind of cancer.”

Dr. Heller said this could take “three to five years.”

warrior

warriorAI can be used not only for early detection but also to speed up other blood tests.

For cancer patients, contracting pneumonia can be fatal, and because there are approximately 600 different microorganisms that can cause pneumonia, doctors must perform multiple tests to identify the infection.

But new blood tests are simplifying and speeding up the process.

California-based Karuis uses artificial intelligence (AI) to help accurately identify pneumonia pathogens and select appropriate antibiotics for them within 24 hours.

Alec Ford, CEO of Karius, said: “Before we had testing, patients with pneumonia would have had 15 to 20 different tests during their first week in hospital to determine their infection – the tests cost approx. $20,000.”

Karius has a database of microbial DNA containing tens of billions of data points. A patient's test sample can be compared to this database to determine the exact pathogen.

Mr Ford said this would not be possible without artificial intelligence.

One challenge is that researchers currently don’t necessarily understand all the connections that AI might make between testing biomarkers and disease.

Over the past two years, Dr. Slavé Petrovski has developed an artificial intelligence platform called Milton that uses biomarkers in the UK Biobank data to identify 120 diseases with a success rate of more than 90%.

Finding patterns in such large amounts of data is the only thing artificial intelligence can do.

“These are often complex patterns where there may not be one biomarker, but you have to consider the whole pattern,” said Dr. Petrovsky, a researcher at pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca.

Dr. Heller uses similar pattern-matching techniques in his ovarian cancer research.

“We know the sensors bind to and respond to proteins and small molecules in the blood, but we don't know which proteins or molecules are specific to cancer,” he said.

Broader data, or lack thereof, remains a shortcoming.

“People weren't sharing their data, or there wasn't a mechanism to do that,” Ms Moran said.

Ocra is funding a large patient registry containing electronic medical records of patients whose data researchers can use to train algorithms.

“It’s still early days — we’re still in the Wild West of artificial intelligence,” Ms. Moran said.