'It's really devastating': Incarcerated firefighter's life battling Los Angeles wildfires

Every other day, Joseph McKinney, Joseph Sevilla and Sal Almanza wake up around 4 a.m. to play at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena Have breakfast at base camp at the Rose Bowl before heading into the San Gabriel Mountains to battle one of the most destructive fires in Los Angeles County history.

Their firefighting duties are assigned daily by the captain and may include containment work, structural defense, or clearing dry vegetation to stop a fire from spreading. The men work 12-hour or 24-hour shifts, and if they choose the latter, they take the next day off to base camp to recuperate.

While McKinney, Sevilla and Almanza perform the same duties as other first responders, they are not professional firefighters. The three are being held at Fenner Canyon Sanctuary 41, a medium-security prison in Vallermo, an unincorporated part of the Antelope Valley in Los Angeles County that houses people convicted of arson, People who commit crimes such as robbery and assault.

The men are part of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation's Protected Fire Camps program, which operates 35 fire camps across the state. Participants respond to natural disasters such as wildfires and floods. When they're not dealing with emergencies, they help maintain the park and assist with sandbagging.

As of Friday, more than 1,100 incarcerated firefighters were battling the Palisades and Eaton fires, which have claimed at least 27 lives and are shaping up to be one of the costliest natural disasters in U.S. history. Historically, incarcerated firefighters make up 30% of California’s wildfire force.

Incarcerated firefighters at Fenner Canyon Conservation Camp 41 earn between $5.80 and $10.24 per day, with Cal Fire also providing $1 per hour during emergencies.

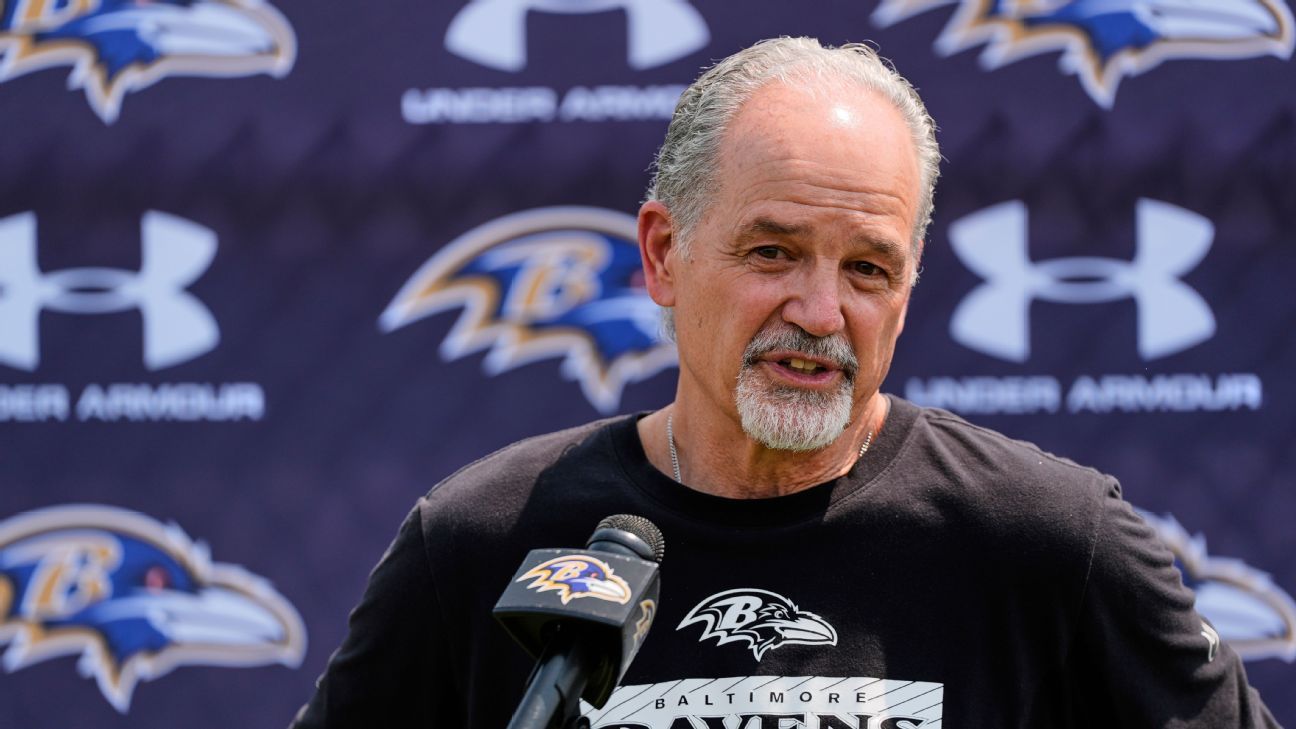

(Pedro Calderon Michel)

“We're not used to seeing damage of this magnitude,” McKinney said. “We're not used to seeing this because we normally have wildfires. But it's really devastating because there's so much damage here.”

These men initially join the program to shorten their sentences—they receive either one or two days of credit for each day they work, depending on the length of their sentence. But some of them said that after joining, they found the work rewarding and the opportunity to pursue potential career paths upon release.

Almanza initially tried unsuccessfully to pursue a career in firefighting about a decade ago.

“I just thought it was so funny that I ended up in a situation that I wanted to be in a long time ago,” the 42-year-old said. “It comes full circle and comes back.”

Before Sevilla, 23, went to prison, he had been bouncing around, from working at a biotech company to working at a fast-food restaurant. He plans to work in wildland firefighting after he is released from prison.

“I ended up falling in love with it,” he said. “You have to come out into this wilderness. You can get outside and move around. So in addition to staying healthy and doing physical exercise, you can do mental exercise because you know you're serving the community and doing something good for the people. “

For McKinney, being on the front line means a lot to him. The 44-year-old man once lived above the Crown City pawn shop in Old Pasadena. He remembers the moment they battled the fire at the Mount Wilson Observatory, looking out at the black smoke and wondering if the fire would ever stop.

Most of all, these people said, they're grateful for the outpouring of support from the community.

“It’s very positive mentally for us,” McKinney said. “Sometimes when you're incarcerated you can feel alone, you can feel like you're excluded from your community or from society. This shows that even from where we are, we can still have a huge impact ”

To qualify for the program, participants must have eight years or less remaining on their sentence, be physically and mentally fit to perform the required duties, and have not been convicted of certain charges, such as arson, rape and escape history.

The program has faced criticism, largely because incarcerated firefighters are paid between $5.80 and $10.24 a day, plus Cal Fire's $1 an hour during emergencies. The program has also been criticized for associated health risks and the notion that it uses firefighters to perform “forced labour.”

From left: Joseph McKinney, Joseph Sevilla, Sal Almanza.

(Pedro Calderon Michel)

Research from the American Civil Liberties Union and the University of Chicago Law School shows that incarcerated workers are more likely to be injured than professional firefighters. At least four incarcerated firefighters died on the front lines, and more than 1,000 required hospitalization over a five-year period, according to the American Civil Liberties Union report.

The path to becoming a firefighter after prison is unclear. For example, getting municipal firefighting jobs can be difficult because they require EMT certification—certification that felons cannot obtain under California law.

In 2020, Governor Newsom signed Assembly Bill 2147 to help expunge the criminal records of non-violent offenders involved in fire protection programs. Rep. Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) also recently introduced AB 247, a bill that would give incarcerated firefighters a raise, putting them on the same wage as the lowest non-incarcerated firefighters.

Supporters of the program stress that participation is voluntary and that it provides inmates with future career opportunities. The incarcerated firefighters are already working with Cal Fire, the U.S. Forest Service and other capable firefighters, according to the corrections department. Cal Fire also worked with the Department of Corrections, the California Conservation Corps and the Anti-Recidivism Coalition to develop an 18-month training and certification program at the Ventura Training Center.

When they're not battling fires, the men rest, eat, shower and do laundry at the base camp. They can also call friends and family from a shared phone – something that's impossible when they're on the front lines of a fire.

But corrections officials said they are evaluating new technology that would allow the men to carry mobile devices and make calls while fighting fires.

Firefighters can be at a fire scene for weeks on end, making it difficult to communicate with loved ones. Amanza said he was recently able to call his 12-year-old son, whose birthday was in two days.

“Before I left, I had to tell him that I loved him, but I probably wouldn't be able to wish him a happy birthday,” he said.

Inmate personnel set fires in dense brush along Madera Road as firefighters tried to stop the Easy Fire from crossing the road into Thousand Oaks, California, on October 30, 2019.

(Brian Vanderbrugge/Los Angeles Times)

Los Angeles-based Anti-Recidivism Coalition Start a fundraiser As of Friday, the organization had raised more than $40,000, according to executive director Sam Lewis.

“The beauty of this terrible tragedy is the unity it created throughout Los Angeles County,” Lewis said. “These two fires took a toll on people.”

Lewis said the money will be used to purchase meals, toiletries, gear and replace shower facilities at one of the campsites. Any remaining money will be used for inmate commissary accounts or to provide scholarships for former incarcerated firefighters.

“It's a way for the public to express our gratitude for the fact that you are putting yourselves at risk to save our property,” Lewis said. “They are literally putting out this fire that has taken away so many lives. The fire of life.”