Secretary of Energy oversees major scientific research and U.S. nuclear arsenal

The U.S. Department of Energy was created in 1977 from the merger of two agencies with different missions: the Atomic Energy Commission (responsible for developing, testing, and maintaining the nation's nuclear weapons) and the Energy Research and Development Administration (responsible for the collection of domestic energy research programs).

Today, the department describes itself, some might say, as “one of the most interesting and diverse agencies in the federal government,” an understatement. Its annual budget is approximately $50 billion and supports approximately 14,000 employees and 95,000 contractors.

The Secretary of Energy advises the President on energy policy and directs energy and nuclear weapons production programs. As researchers who study energy efficiency and national security and work with the Department of Energy, we see that the Secretary of Energy needs to be able to think long-term and make strategic decisions, sometimes even with incomplete information. A strong grasp of science, engineering and energy technologies is helpful, as is the ability to lead large organizations and work with Congress.

scientific research and development

The Department of Energy's Office of Science supports the majority of basic scientific research in the United States, including fusion energy, particle physics, chemistry, and materials science. Together with the agency's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, it manages a research portfolio with a budget of about $12 billion, nearly as large as the budget of the National Science Foundation, another major federal funder of basic research.

Craig Fritz/Flickr

Many energy secretaries have accomplished great things by supporting and directing research. For example, during the first Trump administration, Rick Perry recognized potential cyberterrorism risks to U.S. energy infrastructure and supported artificial intelligence research. This led to the agency establishing the Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security and Emergency Response.

Steven Chu, who led the department from 2009 to 2013 under former President Barack Obama, launched the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), which focused on new cutting-edge Energy innovation, but the sector attracted premature attention from private institutions. -Sector investment. The ARPA-E program has spawned more than 100 new companies and resulted in more than 1,000 patents in a variety of energy technologies, including hybrid electric aircraft, airborne carbon dioxide capture and improved electricity transmission.

Most recently, during the Biden administration, Jennifer Granholm has focused on working with business and industry to deploy clean energy technologies to support U.S. climate goals. The effort includes providing grants, loans and rebates to fill supply chain gaps and promote domestic manufacturing of components such as advanced batteries and solar panels.

Research results

Much of the research funded by the Department of Energy can take years to produce results with commercial applications, but it has already produced some notable successes.

The agency has invested heavily in shale oil research since the late 1970s. Combined with additional research and development by private energy companies, the Department of Energy helped develop hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. These technologies have revolutionized oil and gas production, making the United States the world's largest oil and gas producer.

Department of Energy funding supports the commercialization of efficient and long-lasting LED lights. It has also made breakthroughs in other energy-saving technologies, solar and wind energy production, battery technology, and geothermal and wave energy. The agency provides critical support for research into nuclear fusion, which promises to be a clean and abundant energy source, although it is currently far from commercialization.

There is also a large amount of energy policy in the United States that is outside the control of the Department of Energy. For example, energy production leases and licenses on public lands and federal waters are granted by the Department of the Interior.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is an independent agency that controls the siting of oil and natural gas pipelines and interstate transmission lines. Another independent agency is the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which is responsible for licensing and regulating the nuclear power industry.

Nonetheless, the Secretary of Energy often advocates broad strategies that overlap with the missions and authorities of other federal departments and agencies.

Nuclear weapons and national security

Another DOE mission – developing and sustaining nuclear weapons – is directed by the National Nuclear Security Administration, a semi-autonomous agency within the department. Organizationally, the NNSA is the great-grandson of the Manhattan Project, the post-World War II incarnation of the Manhattan Project that developed America's first atomic weapons.

The NNSA is led by an administrator who also serves as Under Secretary of Energy for Nuclear Security, a Senate-confirmed position. When an energy secretary’s background is in domestic energy — as was the case with Chris Wright, the oil executive chosen by President-elect Trump to lead the agency — the NNSA leader is likely to be more concerned about national security issues. is particularly influential.

Of the Department of Energy's 17 national laboratories, three—Los Alamos Laboratory, Sandia Laboratories, and Lawrence Livermore Laboratory—are formally regulated by the NNSA. Other agencies receive significant funding from the National Nuclear Security Administration and play a role in maintaining the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

The NNSA also oversees experimental and testing facilities and other sites involved in the design, production, and testing of nuclear weapons. It is responsible for the storage and protection of warheads not deployed at military installations, as well as the removal of decommissioned warheads.

An independent Office of Environmental Management oversees the cleanup of nuclear research and production sites, some of which have contamination dating back to World War II. It is the world's largest environmental cleanup program, costing about $8 billion a year – one-sixth of the agency's entire budget. It handles large amounts of radioactive waste, spent nuclear fuel, excess plutonium and uranium, as well as contaminated facilities, soil and groundwater.

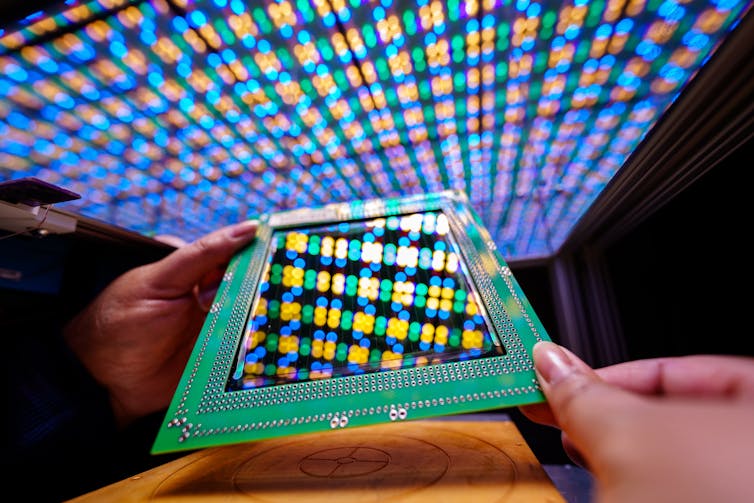

Jeff T. Green/Getty Images

The National Nuclear Security Administration plays a key role in preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the materials and technologies needed to make them. It is part of the intelligence community with deep technical expertise and responds to nuclear and radiological threats globally.

Finally, the National Nuclear Security Administration designs and supports the nuclear reactors that power naval ships and submarines around the world.

Historically, NNSA managers have had significant autonomy. Most administrators bring deep technical and policy expertise to the job. Some are retired Navy or Air Force officers who worked on nuclear weapons or naval propulsion systems. Others are long-tenured researchers at DOE laboratories.

Aging weapons, grounds and workers

The next Secretary of Energy and Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration will face significant technical, economic, and managerial challenges. The National Nuclear Security Administration has been working for years to modernize aging and underfunded nuclear weapons production infrastructure. At the same time, the Energy Department is working with the Defense Department to update U.S. nuclear weapons and strategic nuclear forces — bombers, ballistic missiles and submarines — to deter threats from other nations. The effort could cost as much as $1.7 trillion over several decades.

Many of the NNSA's major modernization projects are over budget and years behind schedule. The U.S. Government Accountability Office recently reported that the National Nuclear Security Administration needs to improve its program management practices to control costs and successfully execute these expensive initiatives.

The incoming administration must also recruit and maintain a highly skilled workforce for the nuclear security program. Many employees who were eligible for retirement have left the agency. More people will exit over the next four years, often because of private sector wages and better working conditions.

While the Department of Energy touts its high-tech labs and research facilities, the agency's people are equally critical to its mission.

This story is part of a series of profiles on cabinet and senior executive positions.