The latest hot spot for marine life may be the underwater volcano that erupts in Oregon: NPR

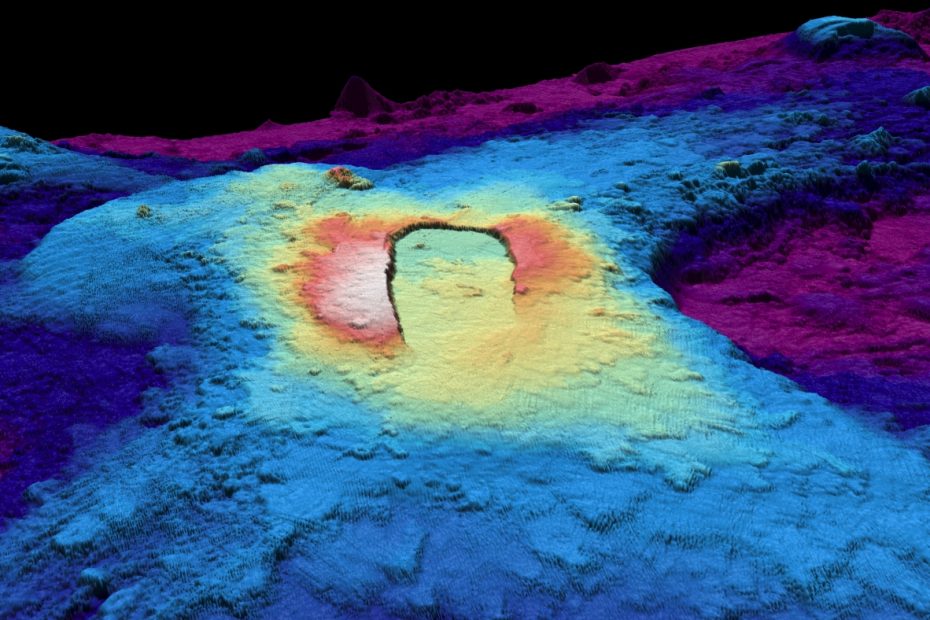

A three-dimensional diagram of the seabed shows the shape of the crater of the axial sea mountain volcano. Warm colors show lighter depths and cooler darker colors.

Susan Mel/Oregon State University

Closed subtitles

Switch title

Susan Mel/Oregon State University

Underwater volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest It is expected to explode for the first time in 11 years this year, which could spark a lot of activity from marine life in the region.

The volcanic axial sea mountain is about one mile below the sea surface and about 300 miles from the Astoria coast, Oregon. It has exploded three times over the past 30 years, with the most recent outbreak in 2015 According to Bill Chadwick, a part-time job at Oregon State University, he is helping predict the eruption of the volcano.

Since the axial sea and mountains are far away from the shore, humans will not be affected. However, the pressure generated by the upcoming magma flow creates pressure that heats the sea water to more than 700 degrees Fahrenheit. As the sea water passes through the cracks in the volcanic rock, it picks up the minerals that spew out of the vents, creating black smoke.

These are called water-heat ventilation holes, just like hot springs on the seabed. Chadwick of OSU says all the warmth and nutrition from the vents makes it a hot spot for plants and animals.

“The food chain here is based on the chemical reactions that microorganisms produce little energy, and then animals either symbiotically or eat them,” he said. “Then there is a whole chemical energy-based ecosystem around these hydrothermal vents and many weird animals.”

When an outbreak occurs, some ventilation holes may be covered with magma, but they appear again as the magma regroups in the earth.

Nevertheless, these chemicals do not make them high enough to affect the atmosphere due to the depth of the mountain and the distance from the shore. Chadwick said that although scientists predict that eruptions will trigger small earthquakes (2s and 3s in Richter), they are not enough to cause major damage to ocean or land life.

It's hard to determine when it's totally expected to happen.

Although Chadwick and other researchers were right about the last eruption, he noted: “My predictions have had some success and some failures.”

These predictions are based on the cycle of inflation and ventilation. As magma accumulates under the volcano, the seabed expands. After the eruption, it fell off.

“It's kind of like a balloon filling the air, and you radiate some air and then you fall down,” Chadwick said. “Now we've seen it a few times now, and it's pretty reproducible. Each time it expands to about the same level and then triggers the eruption. So this prediction is based on this pattern we've seen before.”

However, the pattern is not as linear as before. Chadwick said scientists have not found the cause yet.

Researchers were able to detect these changes through the Ocean Observation Initiative funded by the National Science Foundation. This is a series of ropes that extend from the coast to the volcano. They are decorated with more than 140 devices, such as pressure sensors.

Due to the program and the remote location of the volcano, the axial sea mountain has become crown jewels to develop long-term predictions for underwater volcanoes.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, scientists estimate that 80% of volcanic eruptions occur underwater. But predicting underwater volcanoes is more difficult than land volcanoes because they don’t have much turmoil, Chadwick said. “We kind of experimented in this place where false alarms can be issued,” he said.

The bet to monitor underwater eruptions is also low.

“We can make predictions and if they are wrong, it won’t have a negative impact on people or have no economic impact.”