Death as a grant for diversity, young scientists fear that this will bother their careers: lens

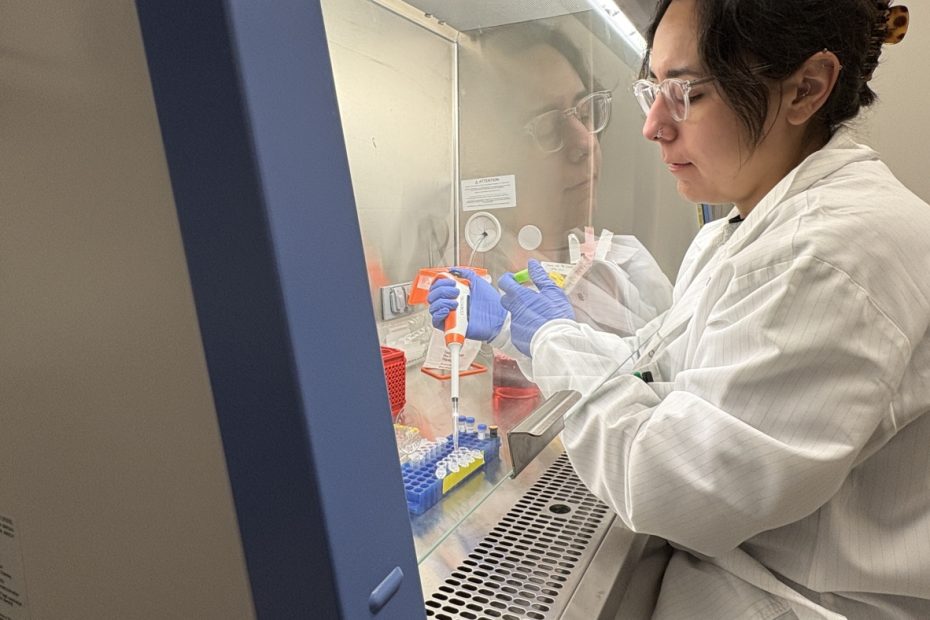

Adelaide Tovar, a postdoctoral geneticist at the University of Michigan, prepared cell samples in a science lab on campus. Tovar is one of 200 young scientists who will lose research funding as the Trump administration abruptly ends the National Institutes of Health’s mosaic grant program. (Mike Hawkins)

Mike Hawkins

Closed subtitles

Switch title

Mike Hawkins

University of Michigan scientist Adelaide Tovar studied genes related to diabetes and used to feel like an impostor in the lab. Tovar, 32, grew up and was the first person in her family to graduate from high school. In her first year in college, she realized she didn’t know how to study.

But after years of studying biology and genetics, Tovar finally got the evidence of her belonging. Last fall, the National Institutes of Health awarded her a well-known grant. It will fund her research and make her a university professor and eventually set up her own lab.

“I feel like winning the award is a form of acceptance, like I finally got it,” Tovar said. “But I think many of us are worried now that it will poison the rest of our careers.”

Tovar is one of nearly 200 early career scientists nationwide, whose research and work prospects have been jeopardized due to the sudden termination of NIH’s mosaic grant program, one of many who ended with a comprehensive cut in a trans-federal scientific institution. The grant was created by the first Trump administration to develop a new generation of biomedical research scientists and then refunded in the clearance of the ongoing diversity, equity and inclusion programs in the second Trump administration.

In an interview with KFF Health News, Tovar and three other grant recipients feared that the loss of funds (plus Donald Trump’s crusade on the diversity program) could change a grant that would have developed their careers into flaws, leaving their careers in flaws, which could have made their work and money damaging their work, thus making their research possible.

Columbia University scientist and mosaic grant award Erica Rodriguez used a microscope to help her tour solder as part of brain research. The Trump administration has returned the mosaic grant program as part of the clearance program. (Taylor Gibson)

Taylor Gibson

Closed subtitles

Switch title

Taylor Gibson

“We may end up being blacklisted by NIH because of this award,” said Erica Rodriguez, a grant recipient at Columbia University.

“Because it’s not only for people with different backgrounds, but for those who offer different backgrounds to people with different backgrounds,” she said.

The NIH grant document said the Mosaic program was created in 2019 – the abbreviation for “maximizing opportunities for independent careers in science and academics”, aiming to provide early support to promising scientists from “underrepresented backgrounds” with a long-term goal of “enhancing diversity among biomedical researchers.”

The five-year grant is awarded to scientists who have completed their PhD degrees at universities across the country and work in research laboratories. During the first two years, scientists usually earn $100,000 to $150,000, which is mainly used to pay salaries.

By the third year, scientists are expected to be hired as a professor, possibly at another university, with grant funds helping them start their own research labs. In the last three years of the grant, the funding increased to about $250,000 a year to purchase supplies and hire other early career scientists to work in the lab, completing the cycle.

Mosaic winners were selected using definitions of diversity beyond race, gender, and disability. It includes those who grew up in poor families or rural areas, or raised by parents without a college degree. Many of the people who chose for this grant have a history of supporting other budding scientists from underrepresented backgrounds.

Mosaic Fund studies cancer, Alzheimer's disease, spinal cord injury, cochlear implant, fentanyl overdose, stroke recovery, neurodevelopmental disorders, etc.

However, according to a NIH email reviewed by KFF Health News, NIH has notified most mosaic recipients in recent weeks that “termination” of the program “termination” and their funds will end this summer regardless of the year remaining of their grants. Other winners received no official notice and only knew through word of mouth that their funds had been cancelled.

Vianca Rodriguez Feliciano, spokesman for the Ministry of Health and Human Services, confirmed in an emailed statement to KFF Health News that Mosaic has been funded. She said grants are no longer associated with agents’ priorities or the president’s execution order “eliminate waste, ideologically driven DEI programs.”

Trump signed one of the orders on the first day of the White House directing the entire federal government to end plans to promote diversity, calling them “shameful,” “immoral” and “huge public waste.”

Diversification plans have been cut, including at NIH and other HHS agencies, which have canceled billions of dollars in grants since March. The NIH issued a notice on April 21 saying they prohibited receiving grants if there is a DEI program and said the agency could “retrieve all funds” from those who do not comply.

“At HHS, we are committed to returning our institutions to their tradition of golden standards, evidence-based science – not driven by political ideology,” said Rodriguez Feliciano. “We will no longer be determined with firmness to identify the root causes of chronic disease epidemics, which is part of the mission to make America healthy again.”

Many mosaic scientists focus on chronic diseases. For example, Tovar looked at specific genes that make people more vulnerable to diabetes, which affected about 38 million Americans, including some who responded poorly to existing therapies.

“We have a lot of treatments for diabetes, which are very useful to the people they work for,” Tovar said. “In my research, I used genetics to help find better targets for drug so that we can find drugs for people who have not yet had treatments.”

Tovar and other mosaic recipients describe how sudden losses in funding will put research and careers into turmoil. Some postdoctoral researchers may lose their current jobs when their funds are dry within a few months. Winners of competing professor Jobs will lose research funding, making them stronger candidates; those who have already hired will receive less salary and supply in their research labs.

Ashley Albright, 32, grew up in rural North Carolina and is now a scientist at the University of California, San Francisco Chorus Framea large single-celled organism with regeneration ability. She plans to start applying to Professor Jobs this fall.

Albright said mosaic funding would give her “better dreams” to give other scientists from different backgrounds the opportunity to work in her research lab.

“I feel frustrated,” she said. “I feel like someone is heading for half her life. …I’ve spent the past decade in graduate school and my postdoctoral efforts are dedicated to this effort so that I can do science but can help others do science.”

Hannah Grunwald, 33, a grant recipient at Harvard University who studies eyeless caves to better understand complex genetic traits, said one of her worst concerns is that when the White House orders schools to abandon their DEI program and rejects those who don’t follow Trump’s agenda, they won’t hire Moses-style winners.

“In our community, there is a lot of debate about what we should say on our resume,” Glenwald said. “I just don’t know if the grant was cancelled because it has to do with diversity and will limit my ability to get funding in the future.”

The mosaic termination was promptly condemned by several scientific organizations that received grants in close collaboration with award scientists, some of whom called it “short-sighted” and “rewind.”

Since the beginning of Mosaic, Mary Munson, president of the American Society of Cell Biology, has directed the winners, whose face was choked and covered because she believes the grant may eventually stop them from retreating.

“I feel like everyone has lost everyone because they are amazing,” Mumson said. “But without them doing that, research that would not be completed would be a huge loss for society.”

Stefano Bertuzzi, CEO of the American Society of Microbiology, also directed the award winners, saying the massive termination of Mosesic and other NIH grants could have a cumulative effect that would kill decades of scientific innovation.

Bertuzzi, who immigrated from Italy 19In the 1990s, due to the strong U.S. funding for science, scientists would not stay or flock to a country where research funds disappeared politically.

“We will lose a full year of scientists,” Bertuz said. “The rest of the world will thrive.”